Ivanisevic the Fortifications and the Intramural Housing in the Lower Town

Transcript of Ivanisevic the Fortifications and the Intramural Housing in the Lower Town

Sonderdruck aus

Falko Daim · Jörg Drauschke (Hrsg.)

Byzanz – das Römerreich im MittelalterTeil 2, 2 Schauplätze

R G Z MRömisch-GermanischesZentralmuseum

Forschungsinstitut fürVor- und Frühgeschichte

Gesamtredaktion: Kerstin Kowarik (Wien)Koordination, Schlussredaktion: Evelyn Bott, Jörg Drauschke, Reinhard Köster (RGZM); Sarah Scheffler (Mainz)Satz: Michael Braun, Datenshop Wiesbaden; Manfred Albert,Hans Jung (RGZM) Umschlaggestaltung: Franz Siegmeth, Illustration · Grafik-Design,Bad Vöslau

Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek

Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation inder Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografischeDaten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar.

© 2010 Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums

Das Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Die dadurch begrün detenRechte, insbesondere die der Übersetzung, des Nach drucks, derEntnahme von Abbildungen, der Funk- und Fernsehsen dung, derWiedergabe auf photomechanischem (Photokopie, Mikrokopie)oder ähnlichem Wege und der Speicherung in Datenverarbei -tungs anlagen, Ton- und Bild trägern bleiben, auch bei nur auszugs-weiser Verwertung, vor be halten. Die Vergü tungs ansprüche des § 54, Abs. 2, UrhG. werden durch die Verwer tungs gesellschaftWort wahrgenommen.

VUJADIN IVANISEVI ’C

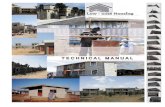

CARIČIN GRAD – THE FORTIFICATIONS

AND THE INTRAMURAL HOUSING IN THE LOWER TOWN

The research carried out in Caričin Grad (dist. Lebane, SRB) in recent decades has emphasised the signifi-cance of this archaeological site, located in the western part of the province of Dacia Mediterranea, nearthe border with Dardania. This was once an urban centre that expanded between the fourth and the sixthdecade of the 6th century on an expanse of land far removed from the communication routes in the fertilevalleys along the Pusta Reka, Jablanica and Southern Morava rivers and the mine shafts exploited on thehillsides of the Leskovac Plain. The city was built in a rural region and is a unique example of late urbani-sation in the region of northern Illyricum (fig. 1).Caričin Grad extends over an area of about 20ha, the principal part of which was the city core covering anarea of 8ha, at the top of a ridge. It consisted of three entities: the Acropolis, the Upper and the LowerTown, defended by three rings of stone and brick defence walls. Spacious suburbs surrounded by a palisadedefence wall stretched out on the slopes around this complex and extended as far as an artisans’ centre atthe foot of the hill on the riverbanks, and a dam with a lake (fig. 2). The archaeological exploration of the city began in 1912 and brought to light numerous basilicas, publicbuildings, a main square, broad streets and porticos, an aqueduct, a large cistern, a developed water supplyand sewage network, baths, the dam with the lake, artisans’ furnaces, as well as a system of fortificationsin the immediate neighbourhood. The urban structure of the city itself was a combination of the Hellenistictradition, Roman heritage and the early Byzantine concept of a city. The majority of the buildings inside thestone walls – the intramural area – were public buildings or the seats of important state institutions, prin-cipally the Church and the Army1. Summing up all the data collected thus far, Caričin Grad was undoubt-edly an important regional centre. In view of the data from historical sources, the 11th Novel of Justinian I 2

and the accounts by Procopius3 and John of Antioch4, the remains of the city may well be those ofJustiniana Prima, the metropolis erected by the Emperor Justinian I close to his birthplace5. According tothe 11th Novel, Justiniana Prima was to have become the seat of the praetorian prefect of Illyricum and anarchbishopric with jurisdiction over the whole of the diocese of Dacia and Macedonia II. The transfer of theprefecture to Justiniana Prima remained a ‘dead letter’, owing to the uncertainty caused by the barbarianincursions into Balkan territory. On the other hand, according to the later 131st Novel, the city was grantedconfirmation of the prerogatives of the Archbishop of Justiniana Prima with jurisdiction over the entirediocese of Dacia. Justiniana Prima remained primarily a church administrative centre and a garrison city, aswell as an important regional centre. The fact that the population abandoned the city at the beginning ofthe 7th century can be linked with the attacks by the Slavs and the loss of Byzantine control over virtuallyall of Illyricum.The complex of the Acropolis with its cathedral, baptistery and adjacent administrative buildings was in theservice of the Church. The role of sacral component can also be seen in the building scheme of the Upperand the Lower Town, and in the area outside the urban core6. However, it should not be forgotten that

1Byzanz – das Römerreich im Mittelalter · Daim/Drauschke

1 Poulter, Transition 20-21.2 Novellae 94.3 Procope, De aedif. 4, 1.

4 John of Antioch, Chronici Fragmenta 339.5 Kondić / Popović, Caričin Grad 367-371.6 Duval, Architecture 399-480.

the military administration and its buildings located in the south-western quarter of the Upper Townundoubtedly also played a role7. The Lower Town with its public facilities, notably the large cistern, as wellas two unearthed basilicas and the baths, occupied a special place in the planning of the city. The resultsof electro-magnetic surveying prove the existence of other public facilities in this area. They occupied theeastern part of the Lower Town, while one structure is recorded to have existed on the southern side ofthe large cistern. These tests also revealed that there were no traces of public buildings in the southern partof the Lower Town. However, the tests did reveal a residential quarter with numerous private buildings,which presented a contrast to the buildings unearthed thus far in Caričin Grad. For this reason, in 1981, aseparate project was launched to explore the horizon of the city where the local inhabitants had lived; thisproject was completed in 2008.The research was carried out in two main stages, one from 1982 to 1990, when work had to be suspended,and then from 1997 to 2008. The first stage consisted of exploring the central part of the settlement, whilethe second stage involved completing the excavation of the residential quarter in the area between the

2 V. Ivanisevic · Caričin Grad – the Fortifications and the Intramural Housing in the Lower Town

7 Bavant, Identification 123-160.

Fig. 1 Late Roman Illyricum.

southern street in the east, the southern gate of the Lower Town in the south-east, and the defence wallto the south and west. An area of about 80m was excavated in a north-south direction, and 70m in aneast-west direction (fig. 3). On this occasion, we were able to examine the fortification, the western andsouthern curtain walls with towers, access to flights of steps, the southern gate, as well as the remains ofthe aqueduct, parts of the southern street and its porticos. We did not investigate the northern part of thesettlement, which extended further northwards to a larger structure erected next to the southern side ofthe large cistern reservoir, opposite to the basilica with a transept. In 2002, the programme of works was

3Byzanz – das Römerreich im Mittelalter · Daim/Drauschke

Fig. 2 General plan of Caričin Grad.

completed with the excavation of a complex at the south-eastern corner tower of the Lower Town and,subsequently, of the southern vallum; this investigation was completed in 20088.The only »organised« intramural housing explored inside the city’s defence walls was in the area of thesouth-western part of the Lower Town. The residential and artisanal facilities were already known. Thus,we at least defined the structures that were added in other parts of the city next to official buildings, oreven in their interiors, and in the spaces of the porticos. These structures differed significantly from the offi-cial architecture since they were constructed of stone bonded with clay, while the upper floors, if theyexisted, were built of adobe, timber and cob. A row of such structures is recorded to have existed in theUpper Town within the complex of buildings west of the circular city square9, as well as in the Lower Town,in the space west of the basilica, and between the basilica with the transept and the eastern street, at thepoint of the southern portico10. Similarly to those erected in other quarters of the city, V. Popović inter-preted these additions as being part of the stratification of the city’s urban structure that began during therule of Justin II and the settlement of newcomers in the city11.Judging by the research results from the residential quarter in the south-western part of the Lower Town,the process of settlement inside the city walls had started much earlier, during the reign of Justinian I. We

4 V. Ivanisevic · Caričin Grad – the Fortifications and the Intramural Housing in the Lower Town

8 This overview is based on the chronicles of excavations publishedin Mélanges de l’École française de Rome: Moyen Âge, Tempsmodernes 97, 1985, 883-887. – 98, 1986, 1177-1181. – 101,1989, 327-332. – 102, 1990, 277-282. – 103, 1991, 442-448. –109, 1997, 645-651. – 110, 1998, 973-976. – 112/2, 2000,1087-1094. – 113/2, 2001, 963-969. – 114/2, 2002, 1095-1102. – 115, 2003, 1021-1027. – 117/2, 2005, 791-796. –

118/2, 2006, 387-394. – And Leskovački zbornik 38, 1997, 419-424. – 39, [1998] 1999, 489-496. – 40, 2000, 335-340. – 42,2002, 55-68. – 45, 2005, 23-36.

9 Kondić / Popović, Caričin Grad 68-74.10 Kondić / Popović, Caričin Grad 129.11 Popović, Desintegration 563-566.

Fig. 3 Caričin Grad. South-western quarter of the Lower Town.

discovered that the said quarter developed in the area that had not been urbanised or, to be more precise,in the spaces where the construction of public buildings had commenced but had never been fullycompleted.An equally important question arising from the investigation of the Lower Town was exactly when theseimportant building clusters actually came into being. According to V. Kondić and V. Popović, the defencewalls of the Lower Town and the majority of structures were not constructed until the fifth decade of the6th century, after the first Slav incursions. In support of this dating, the authors referred to a series of data,which are summarised here. The position of the basilica with transept served as the basis for their chrono-logical dating. The basilica was located in a different direction to that of the high street, the defence wallsand the other structural ensembles; this would signify that it was integrated with the defence walls of theLower Town at a later time. Furthermore, the southern portico of the northern street and the position ofthe small baths that were virtually reliant on the western tower of the southern gate of the Upper Townoffered proof that the Lower Town developed at a later date. In support of this hypothesis, they mentionedthe canal that ran from the Upper Town, passing below the double basilica and especially below the north -ern tower of the eastern gate of the Lower Town, and also the fact that the western defence wall of theLower Town rested against the south-western tower of the Upper Town. We should add that, ac cor dingto the Latin monogram of Justinian I on the capital of a column and the absence of a monogram of Theo -dora on another, the construction of the basilica with transept was dated after the death of the em pressin the year 54812. On the basis of a follis belonging to Justinian I dating from 544/545, the con struc tion ofthe double basilica was ascribed to some time in the fourth decade of the 6th century. It was un earthedfrom the trench in the foundation of this building13.The answer to the question of when the Lower Town came into being is important for dating the construc-tion not only of this area in particular but of the city as a whole, as well as for dating the establishment ofthe settlement in the south-western quarter of the Lower Town. The excavations of the entire settlementarea in the southern section of the quarter, the western and southern defence walls with their towers, thestreet with porticos, as well as parts of the aqueduct, have provided new chronological evidence for datingthis part of the city. They offer a much more accurate picture of the urbanisation of Caričin Grad14.

THE FORTIFICATION OF THE LOWER TOWN

The construction of the fortifications of the Lower Town was part of a unified construction operation and,along with building the defence walls of the Upper Town, took place during the first phase of the con -struction of the city. Erecting the western and eastern defence walls of the Lower Town was the initialstep in the fortification of the city and closed off the lower parts of the elongated ridge. As it was locatedpractically in front of a flat plateau, the southern curtain wall was defended by a large vallum roughly20m wide.An examination of the Lower Town’s defence walls provided us with a series of clues about how the forti-fications of Caričin Grad would have looked. The excavation works on the south-western corner towerwere particularly significant as they offered important data on the construction phases and when thesetook place. The exploration of this tower and of the western defence wall and the space along the defence

5Byzanz – das Römerreich im Mittelalter · Daim/Drauschke

12 Kondić / Popović, Caričin Grad 169-171.13 Kondić / Popović, Caričin Grad 169-171.

14 Bavant / Ivanišević, Ivstiniana Prima 30-31. – Bavant, CaričinGrad 353-361.

wall was dictated by the need to shed light on the relation of the aqueduct entering the city at this pointand the fortifications. Although this facility was investigated as early as 1947, details regarding its appear-ance were scarce15.On the southern, outer side of the fort, we uncovered two of the aqueduct’s pilasters with square basesand crosswalls on the eastern and western sides; the northern side was organically connected to the towerby the same rows of brick and stone bonded with mortar. The tower’s connection to the aqueduct clearlyshows that both structures were built at the same time. This is illustrated by the position of the tower itself,which was determined by the aqueduct that approached the city from the south-west and, before entering,changed its direction towards the north, and not by the direction in which the defence wall extended, aswas customary. The aqueduct was positioned at right angles to the front of the tower, which was there-fore positioned diagonal to both defence walls. The internal structure of the tower was also dictated by thedirection of the aqueduct: in the centre of the tower, slightly shifted to the east, was a column with a trapezoid base, built in the opus mixtum technique. We refer to the last column of the aqueduct, whichran through the tower and then continued northwards along the route of the western defence wall,beneath the rampart. There was an equal gap of 3m between the columns. We also found this gap be -tween the last northern column and the southern end of the western defence wall, not counting the thick-ness of the northern wall of the tower. The two last arches travelled through the walls of the tower itself,without resting against them. This was done in order to change the route of the aqueduct itself in the spaceof the tower without risking the stability of the tower but, on the contrary, in order to strengthen its base(fig. 4).The tower itself had a square base, 7.75m long sides and walls that were 1.30m thick. The constructiontechnique was opus mixtum and, preserved above the original level of the terrain, were the first rows ofbricks, the zone of stone and the second row of bricks, similar to the defence walls, with which it was struc-turally connected. The only door, 1.20m wide, was positioned next to the inner face of the southerndefence wall.On the basis of this data, we may conclude that the defence wall of the Lower Town dated from the sameperiod as the aqueduct, as in the case of the large cistern – a reservoir around 40×40m in size, which,judging by the information gathered in earlier research work, relied on the western defence wall. We arecertain that the aqueduct, like the cistern, was erected during the first stage of the city’s construction,owing to the water required to carry out large-scale construction work. Otherwise, it would be hard toexplain how it was possible to carry out extensive works in the city without a permanent and plentifulsupply of water. The early dating of the Lower Town’s defences is substantiated by the finds of coins. Asmall find of three folles discovered beside the outer face of the western wall of the south-western cornertower belongs to the coinage struck before the monetary reform in 538.Thanks to the excavation of 42m of the western defence wall, it was possible to collect data on theconstruction method of the defence wall and on how the downward slope of the terrain to the north wasincorporated. This section of the defence wall was built to overcome the declivity in the terrain, by meansof a cascade descent of the foundation. In addition, two large-scale repairs of the wall surface wereobserved on the defence wall, undoubtedly performed as a result of damage caused by water leakingthrough the aqueduct beneath the rampart.In the north-western part of the space investigated, a tower with a rectangular base was discovered thatprojected 4.70m outwards in relation to the defence wall and that was 5.80m wide. The walls were builtaccording to the opus mixtum technique and were 1.30m wide. At the point where the tower was joined

6 V. Ivanisevic · Caričin Grad – the Fortifications and the Intramural Housing in the Lower Town

15 Kondić / Popović, Caričin Grad 130.

to the defence wall, the walls were preserved up to a height of almost 2m, while in the corners they werepreserved to the height of the first alternation of bricks. The entire construction visibly sagged towards thewest. Excavations inside this tower, the base of which was almost square, revealed that the ceiling was inthe form of a cruciform vault. During the excavations, part of the crown of the vault was found among thepieces of brick from the flooring in the first storey.The entire southern defence wall was unearthed, in the section from the sally port to the Lower Town’ssouth-western corner tower, for a length of about 41m. In this section, the curtain wall, which was 2.50mthick, was preserved to an equal height – in the base of the second alternation of bricks – because the localinhabitants had systematically removed the building material. Mid-way between the corner tower and the southern gate, the defence wall was strengthened by a smalltower with a rectangular base, which was 4.60m wide, and projected 4.80m outwards into the field inrelation to the curtain wall. Its walls, which were 1.30m wide, were preserved to the same height as thedefence wall. The entrance, which was 2.40m wide on the outer side and 1.30m on the inner side, hadbrick sidewalls. The interior of the tower was filled with large pieces of the walls that had caved in, but thisdebris did not include bits of the ceiling vault. Beneath the layer of debris was a thick layer of clay that mayhave originated from the flooring of the wooden construction of the upper storey.

7Byzanz – das Römerreich im Mittelalter · Daim/Drauschke

Fig. 4 Caričin Grad. Plan of the south-western tower.

We attach particular importance to the position of the Lower Town’s southern gate, in the central part ofthe southern defence wall, flanked by two towers on the outer side, as well as two flights of steps on theinner side (fig. 5). The sidewalls of the gate, which was 3.25m wide, consisted of large, rectangular andtrapezoid limestone blocks that were carefully hewn and positioned regularly in horizontal rows (fig. 6).The southern façade, the length of which was 3.80m on both sides of the gate, was built in an identicalmanner with a facing of stone blocks, like the northern façade, of which both sides were 3.30m long. Thegate was 3.15m wide at the height of the gate-posts, while it was a little wider on the inside, namely a full4.0m. The threshold, which was 60cm wide, was made of three stone blocks, in which the wheels of cartshad carved grooves. The sockets in which the gateposts were installed were found in the corners of thegateway, beside the threshold. From their arrangement, as well as their relation to the other elements, wedrew the conclusion that the gate doors had been double and that the wings of the gate were of unequalwidth. The paving was mostly preserved in situ, except for the space opposite the small wing and thenorthern part of the gateway, from where the slabs had been extracted. In the space of the gatewaybetween the gatepost and southward outside the gate, we found several fragments of architectonic plas-tics that had collapsed. These were the bases of three pillars, two columns that had supported the parapetfacing, as well as fragments of a profiled architrave. It is unlikely that these blocks originated from thecolonnade of the street portico or from the neighbouring building that had not been investigated, ratherthey were parts of the gate construction that had caved in. It seems that, above the entrance with its gate,there had been a kind of loggia or spacious terrace between the towers that had opened out to the north,with three or four arcades, surrounded by a low parapet wall.Of the two towers flanking the city gate, only the western one was excavated. The interior of that towerhad an almost square base (4.90m in the east-west and 5m in the north-south direction), the outer sideof which was 7.30m wide. The tower projected 6.40m outwards, in relation to the curtain wall. The tower

8 V. Ivanisevic · Caričin Grad – the Fortifications and the Intramural Housing in the Lower Town

Fig. 5 Caričin Grad. Southern gate.

walls of unequal thickness were built according to an opus mixtum technique and were preserved to theheight of the first five rows of bricks and the first row of stone. The width of the entrance to the towerwas 2.40m at the outer opening, and only 1.35m at the inner side. Above the doorposts, preserved at theirfull height, we could distinguish the remains of a damaged semi-circular arch, spanning the entrance. Theentrance to the tower in the later phase was walled up on the outer side by a wall made of spolia bondedwith clay (the bases and capitals from the porticos in the street). The excavation of the tower’s interiorrevealed parts of the broken cruciform vault that had caved in while, beneath it, we noted the remains ofa roughly 0.15m thick wooden platform that had collapsed and that had, most probably, served as a sortof mezzanine, erected above the ground floor, beneath the ceiling vault of the tower. The floor inside thetower, which was the same level as at the foot – an extension of the foundation – was of beaten earth. Init, we discovered parts of half-buried pitoi, containing the remains of carbonised cereal grains. Judging bythese finds, the ground floor of the tower had served as a storage space during the last phase (fig. 7).Just 0.90m to the west of the previously described tower was a postern, 2.10m wide inside, and a narrowentrance, which was 1.50m wide. The floor of the postern, made of beaten earth, was several centimetreslower than the original threshold, which was preserved in situ. The threshold was made of three blocks oflimestone and had only one small pit for a gatepost on the eastern side, which indicates that the posternwas closed by a gate with a single wing. The entrance was later walled up with a wall that was just 0.40mthick and erected according to an opus mixtum technique.The semi-circular arch of a block of steps, which was 2.60m wide at the bottom and 1.70m deep, spannedthe entrance to the postern (towards the interior of the town). Part of the arch was preserved on theeastern gatepost, while the arch itself had collapsed in front of the entrance to the sally port, north of theblock of steps. To the west, the steps continued for 4.80m. Five steps with a height and depth of 0.30mand that were in good condition were positioned at an angle of about 45°.The south-eastern corner tower was one of the most significant structures in the Lower Town. Thanks tothe good condition of the structure with walls over 4.5m high, important data were obtained, which willenable the reconstruction of its appearance. The bastion that projected outwards played an important role

9Byzanz – das Römerreich im Mittelalter · Daim/Drauschke

Fig. 6 Caričin Grad. Sidewall of the southern gate.

in the defence of the city and in the surveillance of the surrounding countryside, which explains its well-developed foundation. The entrance to the tower, which was 1.90m wide, was emphasised by a circularvestibule 3.10m in diameter. It was positioned at the point where the southern and eastern defence wallsjoined. From there, a small vaulted corridor, 1.80m wide, led inside the tower. The tower, which projectedconsiderably from the curtain walls (4.40m to the eastern and almost 7m to the southern curtain) was builton a square base, the sides of which were 8.10m long. The thickness of its walls ranged 1.20m to 1.30mto the north, south and west, and 1.50m to the east. At the farthest point of the wall’s projection, it wasreinforced on the outer side by a crosswall, which was 1.20m wide, and by two columns positioned in thecorners on the inside, creating a kind of niche, which was 3.10m wide. The walls and the defence wallswere built in the regular opus mixtum technique with five rows of bricks (fig. 8).The eastern defence wall in this section was 2.25m wide, while the southern was slightly wider, namely2.50m. On the other side, at the point where it joined the tower itself, it was only 1.20m wide and, at thispoint, the defence wall was not reinforced by a block of steps.The approach to the rampart and the upper storey of the tower led up a flight of steps, which was 1.30mwide, and extended along the eastern defence wall, similarly to the eastern gate of the Lower Town. Theflight of steps rested on three pilasters of different lengths. The first two were 1.60m long, while the thirdwas slightly longer, namely 1.90m (viewed from the circular vestibule). The gaps between them were equaland came to 2.45m. The flight of steps terminated in a structural mass 4.65m long; at the northern partof this, four steps were preserved in situ. The remains of a cruciform ceiling vault that had caved in were discovered in the interior of the tower, withfragments of frescoes beneath. Along the southern wall of the tower, we found the fallen wall of the firstfloor with a fresco in situ, the surface of which was 2.5×1.60m. The fresco consisted of a geometrical orna-

10 V. Ivanisevic · Caričin Grad – the Fortifications and the Intramural Housing in the Lower Town

Fig. 7 Caričin Grad. Tower and postern of the southern gate.

ment in three bands, painted in black, red, white and blue. The lower band, the dimensions of which were2×0.40-0.60m, was painted blue, above which was a white border, between 0.03m and 0.04m wide. Theupper band, which was 0.21m wide, was painted red and featured rhombuses (three were preserved)surrounded by blue dots. This was from the lower zone of frescoes on the first storey, on which imitationmarble panels had been painted.The tower itself was covered by a cruciform ceiling vault at the level of the second storey, while there hadonce been an arch above the eastern niche, parts of which had collapsed into the niche. The tower had amezzanine structure made of beams and planks coated with cob. The floor in the tower was of yellowbeaten soil, while the entry area was paved with stone slabs. A flight of stone steps led inside the tower.The interior of the tower had been burned in a big fire that had spread to parts of the upper storey construc tion, which had collapsed into the interior. Many objects were found in the layer of debris,including fragments of window panes. These fragments indicated the existence of windows in the tower,which was con fir med by the discovery of a window structure in the debris of the wall surface south-eastof the tower.An opus mixtum technique was used to build the lower zones of the tower walls, as well as those of thefirst storey, as evidenced by the discovery of pieces of the wall surfaces that had fallen off the outer sideof the tower. It consisted of alternate rows of bricks and stone scattered around the tower. In the debristhat had fallen off the southern side, we found the remains of the small window mentioned above, witha small arch made of brick. Based on this find, we may assume that the tower had a small window on everyside of the upper storey. The upper floors were constructed exclusively of brick, as evidenced by the largeblocks of the wall surfaces made exclusively of brick. This fact alters the previous thinking that the wholetower was constructed in the opus mixtum technique, with alternate rows of bricks and stone. According

11Byzanz – das Römerreich im Mittelalter · Daim/Drauschke

Fig. 8 Caričin Grad. South-eastern tower.

to the preliminary results, it can be said with certainty that the third storey of the tower was constructedexclusively of brick in order to lighten the load of the structure’s upper sections.Due to the poor foundations or perhaps an earthquake, the tower began to sink very soon, even beforethe end of the reign of Justinian I. Consequently, its base was specially reinforced on the outer side by a1m high layer of yellow and brown clay, poured along the eastern, northern and probably also southernsides of the tower in the time of Justin II, which is corroborated by the find of a half-follis struck during theearly years of his reign. In addition, the defence ditch that protected the approach to the tower from theeastern side was filled in. Similarly, from the inner side, the level of the terrain was raised on the entiresurface in front of the entrance to the tower, as well as along the eastern defence wall, in order to preventwater from leaking into the tower. On this occasion, a new canal was built that channelled the waterthrough an opening built later in the eastern defence wall. The whole venture was, in fact, part of a largerconstruction project aimed at consolidating the foundations of the tower.The defence ditches dug along the southern and eastern sides of the Lower Town played a particular rolein the city’s defence. The large southern ditch that was about 20m wide and that ran along the entirelength of the southern defence wall was clearly visible in the configuration of the terrain (fig. 9). The ditchwas explored in order to establish the nature of its base. The ditch was dug in the soil to a depth of 5m.The bottom of the ditch was shaped like a duct and was 1.40m to 1.50m wide. Its bed was filled withmedium-sized pebbles, between which a layer of sandy earth had formed. Judging by its structure and theaccumulation of sand, it was the drainage duct of the ditch carrying water from the higher, western parts

12 V. Ivanisevic · Caričin Grad – the Fortifications and the Intramural Housing in the Lower Town

Fig. 9 Caričin Grad. Vallum in front of the southern rampart.

of the ditch towards the lower, eastern parts. It is unlikely that this was the base of some kind of defenceconstruction.Investigations of the south-eastern tower complex revealed the remains of another ditch, which ran alongthe eastern side of the south-eastern tower and the eastern defence wall. Its construction was logical inview of the fact that the terrain in this space was roughly flat and enabled easy access to the defence wallsof the fortification. In the later phase, the ditch served as somewhere to throw refuse, as indicated by thenumerous finds discovered in its filling. The earliest layers of the filling were dated by the presence of coinsstruck before the year 538. It was established that the ditch travelled further northwards, following the lineof extension of the Lower Town’s eastern defence wall.

THE SOUTHERN STREET OF THE LOWER TOWN

The route of the southern street was clearly distinguished in the configuration of the terrain. It was exploredfor some 16m in the north-eastern part of the excavation pit, along with the central duct of the sewagesystem that, it should be stressed, was not constructed in a straight line, in relation to the middle of theLower Town’s southern gate and the beginning of this collector. It is evident that the route of the collectorwas shifted by 3° to 4° to the west. The stylobate and the rear wall of the western portico followed thesame slight deviation. This small detail indicated to us that the portico and the southern defence wall werebuilt at the same time and that a mild deviation occurred in the route of the street at the point where theywere joined. We should like to add that the western and eastern porticos were positioned at the samedistance from the defence wall (5m), which resulted in the porticos slanting away from each other.The western portico was explored for a total length of 63m. On the southern section, it ended in a rect -angular column built with a groove for draining away water (gutter) 16. Only two column bases werepreserved in situ on the route of the porticos, while the position of the others can be reconstructed,according to the remains of the skirting and the foundation of the skirting. Along the entire portico, thedistance between the pillars was a little more than three meters. It has to be stressed that, for a long time,it was thought that pillars stood only in front of certain public buildings17. During the excavations in theresidential quarter, a large number of fragmented pillars were discovered, as well as an ionic capital withimpost that had come from the portico. The wall of the portico, erected in an opus mixtum technique, waspreserved only in the foundation, seeing that it had been systematically extracted. The rare, preservedthresholds show that doors had existed in the wall of the portico. The floor in the portico was of beatenearth with ducts in the base for draining off water (fig. 10).On the other side, the eastern portico was completely paved with bricks, which corresponds to the extentof the urbanisation of the Lower Town; only the southern side of this portico was excavated with its firstcolumn and the skirting of the first pillar, together with a small part in the northern section of the excava-tion pit. As mentioned in the introduction, three public buildings of brick and stone had been built in thearea of the south-eastern quarter, one of which had probably been a church. Given that the westernportico had a floor of beaten earth, we may conclude that the western portico was never completelyfinished. This suggests that, in the south-western quarter, the initial plan for the construction of the cityhad not been fully implemented, which is verified by the fact that only one official building had beenerected in this area.

13Byzanz – das Römerreich im Mittelalter · Daim/Drauschke

16 Kondić / Popović, Caričin Grad 99. 17 Kondić / Popović, Caričin Grad 99.

THE HOUSING QUARTER IN THE LOWER TOWN

The housing quarter in the south-western quarter of the Lower Town was located in the area where theconstruction of public buildings had commenced but was never completed. The structures unearthed canbe attributed to several chronological phases. A rectangular building described as the »barracks« where thebuilders of the defence wall were housed was constructed during the earliest phase. A larger, definitelypublic building, the only one of its kind in this area, belonged to the second phase and was made of stonebonded with lime mortar. A row of structures with walls of stone, timber and cob, erected in two rows,one beside the western portico and the other next to the western defence wall, belonged to the third, mostimportant phase. These structures completely negated the structural principles of the first two phases. Aspart of a final, fourth stage, minor alterations were made to buildings in the form of the addition of newpremises to the existing buildings (fig. 11). The use of the free space beside the defence walls and towersand a disregard for the basic plan of the city was characteristic of this phase18.The first facility erected in this space was a rectangular building, 14.50×7.80m in size, which was locatedin front of the entrance to the small tower on the southern defence wall. This facility, traces of which wererecorded mainly as a negative imprint, had been demolished and the walls removed and new structures

14 V. Ivanisevic · Caričin Grad – the Fortifications and the Intramural Housing in the Lower Town

18 Sodini, Archaeology 25-56.

Fig. 10 Caričin Grad. Southern street and western portico.

were erected over the rubble. This building dated back to the first phase in the city’s life during the fourthdecade of the 6th century. Due to the fragmentary state of the foundations, the purpose of the building isstill the subject of speculation. In view of the fact that the building itself was outside the basic urbanscheme of the Lower Town, we assumed that this was a barracks for the builders of the fortifications. Thedating of this structure is supported by the fact that a large lime pit was discovered to the north of it; inthis area, such a lime pit would have been used exclusively for the construction of the fortifications sinceall the buildings in this area were built of stone bonded with clay. The only facility resembling a public building was situated in the north-eastern section and was erectedright behind the street portico. The dimensions of this building were 19.20m in an east-west direction and15.50m in a north-south direction. The building was divided into four long rooms in a north-south direc-

15Byzanz – das Römerreich im Mittelalter · Daim/Drauschke

Fig. 11 Caričin Grad. Schematic plan of the south-western quarter of the Lower Town.

tion and an east-facing spacious courtyard had been added (fig. 12) on its southern side. To the west, thediscovery of a foundation ditch revealed that a wall had enclosed the courtyard. In view of its structure, itis quite clear that this was not a residential building but a public one. We had some reservations aboutidentifying the structure as a stable that may have accommodated some 50 horses. The width of the premises was large enough to accommodate the animals in rows and for them to communicate freely atthe rear. The large courtyard supported this interpretation. It was not long before the entire space was urbanised, not according to the initial plan but according tothe needs of the middle class of civil servants, soldiers, artisans and merchants. As already mentioned, thebuildings were erected in two rows – one row along the western portico and the other in the free spacealong the western defence wall. The buildings can be classified into two basic types: those with a devel-oped organisation and an atrium, and simple houses with a single space. All the buildings were constructedin a similar manner. The lower ground floor was erected of stone, bonded with clay (timber) – opus crati-cium – while the upper storey, if there was one, was made of adobe, or timber and cob. All of them hadtiled roofs. It should be noted that there was also a third type of structure, namely »huts« made of timberand cob. These structures were poorly preserved and it is hard to describe them in greater detail. Thisstratum of the settlement was clearly dated by the finds of numerous coins of Justinian I. The largest facility in this space was a large building with a well-developed foundation resting against thewestern portico. Its dimensions were 23m in a north-south direction and some 20m from east to west. Itwas divided into two separate residential ensembles: the smaller to the north and the larger to the south

16 V. Ivanisevic · Caričin Grad – the Fortifications and the Intramural Housing in the Lower Town

Fig. 12 Caričin Grad. Foundation of the stable(?) and a building from a latter phase.

(fig. 13). On the western side of each complex, there may have been a single-storey building while, on theeastern side, there was a courtyard paved with shale. A portico ran along the northern side of the northerncourtyard, while the southern courtyard was enclosed by a portico on three sides (north, west and south).These two residential units, evidently erected at the same time, were not connected in any way. Access toboth parts was only possible from the western portico.The northern building, 8×6m in size, had a ground floor that was divided into two rooms by a wall of lightmaterial: timber and cob. The smaller, northern room was only 2.40m wide. It may have been a stable. Thecourtyard was narrow because, on the northern side, a deep, 4.50m wide portico with large rectangularcolumns rested against it. In the south-western corner, a construction was discovered that may have beenthe base of a wooden flight of steps.The southern building was 10.40m long and 7.20m wide. This building was considerably larger than theprevious one. Its door, on the eastern side, was positioned roughly at the centre of the building’s façade.The courtyard, which was to the east, was enclosed on three sides by a portico in the shape of the Latinletter U. The central space, which was open, was paved with stone slabs, while the inside covered area hadfloors of beaten earth. Based on the disposition of the walls, there may well have been a flight of steps inthe south-western corner of the portico. The portico underwent certain changes in relation to the originalplan: one wall was added between the column in the north-western corner and the northern wall, as wellas a smaller construction with a rectangular base. It was erected at the northern end of the open court-yard, partly beyond the paving slabs.

17Byzanz – das Römerreich im Mittelalter · Daim/Drauschke

Fig. 13 Caričin Grad. Large building along the western portico.

The other buildings in this area were simple structures with a rectangular base that were changed over timeby the addition of smaller rooms.The typical model of this type is the south-eastern building relied against the wall of the portico, separatedfrom the aforesaid complex by a broad, open sewage duct built of large slabs of slate.The complex consisted of three sections. The main building was a size of 10.30×6.40m and was open tothe east; it had a floor of beaten earth (fig.14). In the flooring, two pithoi containing the remains ofcarbonised cereal grains were unearthed. The southern part of the complex consisted of a kind of narrowcorridor, paved with bricks, which was about 1.60m wide. The southern wall, with a door in its easternsection, was connected by a wall built at an angle to the north-western corner of the main room. An upperstorey was located above these two sections. The existence of this upper storey was suggested by thediscovery of the bottom of a flight of steps into the portico on the street, with two steps in situ. An addi-tion was also made to this complex on the eastern side, involving a smaller room or small courtyard with atrapezoid base, which opened on to the south.Another building with a similar foundation and covering an area of 12.6×7.2m was also erected next tothe portico, north of the large building with the well-developed base on the foundations of the supposedstable. To the west of this building, we recorded a row of partitions, forming small stalls, as well as thebases of what had perhaps been small furnaces.West of this building, in the space towards the defence wall, in the north-western part of the excavation,we noted a smaller structure with a rectangular base, the dimensions of which were 13.40×6.10m, witha room added on to the west. The walls were made of stone bonded with clay while the upper sections

18 V. Ivanisevic · Caričin Grad – the Fortifications and the Intramural Housing in the Lower Town

Fig. 14 Caričin Grad. Building along the western portico and the southern rampart.

were built of partition walls made of timber and cob. The eastern, larger room was divided into twounequal parts by means of a small partition wall. The western, considerably smaller room was built laterand, like the other rooms, had a floor of beaten earth. On both sides of its entrance, from the northernside, we observed two columns built of brick and stone, with gutters attached. The entire complex wasdamaged by a fire, the date of which was determined by the large number of finds of coins, particularly ofMaurice, from around the year 602 (fig. 15).Another smaller building, 10×7m in size, was located south of this facility, opposite the entrance to thetower on the western defence wall. On the western side, this had a 3.5m long portico resting on threecolumns. In contrast to the previous structure, this one faced south, towards another single-structurehouse, facing north. This other structure, which was slightly longer and spanned an area of 11.7×6.2m,had two doors on its northern side. Inside the building, three constructions were seen on the floor and, inthe centre of the room, a pithos in situ; along the eastern wall, there was a pile of earth that resembledthe shape of a bench and, along the western wall, a platform of bricks that may have been the base of afurnace. An annex to this building was created by erecting two more walls: a massive southern wall thatextended to the southern façade of the main building and that was connected to the western defence wall,and a small partition wall that determined the width of the room. Both these buildings, together with theremains of other undefined, smaller structures, may have been part of a larger complex. A building with a rectangular base (12.85×8.30m) with an annex to the west and a courtyard to the south,erected on the approach to the south-western tower, is worthy of particular mention. The heart of thecomplex consisted of a main, rectangular structure with walls made of stone, bonded with clay, and with

19Byzanz – das Römerreich im Mittelalter · Daim/Drauschke

Fig. 15 Caričin Grad. Buildings along the western rampart.

doorposts built of brick and mortar. The door, which was 1.70m wide, was located in the southern walland had a wooden threshold, attached to a stone base. The entrance to the courtyard was situated in theeast and paved with stone. The courtyard was surrounded by a high wall (1.90 long and 0.90m wide) posi-tioned at right angles to the defence wall, and with a column resting on the south-eastern corner of themain structure. The entrance was 1.85m wide. The extraordinary massiveness of the said building, as wellas the existence of one more column next to the defence wall, 3.50m to the west, suggests the existenceof a terrace with a roof that may have been connected by a wooden flight of steps, probably erected nextto the southern façade of the main building, west of the door. Only the western section of the courtyardwas paved with a well-preserved floor of stone slabs. This complex offers a clear example of how thestrategic points and alleys located next to what were crucial elements in the city’s defence, namely thecorner tower and the aqueduct (fig.16), were taken over and usurped.A row of annexes added to the existing buildings marks the last phase of the residential quarter, especiallythose located beside the western defence wall. In keeping with the legal regulations prohibiting construc-tion next to a fortification, they were all erected at a suitable distance from the curtain wall. This rule ceasedto apply during the last decades of the 6th century, after which buildings were constructed right next to thecurtain wall. In our case, the earlier buildings were expanded by adding on new premises that frequentlyrested on the curtain wall itself.In the north-western section beside the tower, two smaller walls made of stone and clay were found. Thesewere parts of a structure that rested against the western defence wall. One wall was positioned at 90° tothe defence wall, while the other rested against the column of the portico that closed off the building

20 V. Ivanisevic · Caričin Grad – the Fortifications and the Intramural Housing in the Lower Town

Fig. 16 Caričin Grad. Buildings along the western and southern rampart.

located in front of the entrance to the tower. The said walls had no foundations but were simply erectedon a later cultural layer.The same applies to the other additions made to the buildings next to the western defence wall. Both struc-tures facing the corner tower were connected by new walls to the defence wall. Thus, next to the struc-ture beside the south-western corner tower, a smaller trapezoid room was added that rested against thewestern defence wall. These added constructions were poorly built and, in addition to the customary shale,were constructed with pebbles and pieces of architectonic plastics made of limestone, as well as fragmentsof bricks and tiles. The walls were not built with care and were narrower than those constructed earlier.Similar constructions are noted in Heraclea Lyncestis (dist. Bitola, MK)19.

MATERIAL CULTURE

The exploration of the residential quarter in the Lower Town revealed a vast number of items of materialculture that, when examined, will provide an insight into this settlement’s place and role in the town, andthe character of the population.More than 10,000 objects were found, not counting pottery fragments and pieces of glass. The majorityof them were items related to everyday life, mainly housing, household equipment and personal items,while a few objects could be linked with cult. The finds relating to economic activities are worthy of partic-ular attention, primarily agriculture and livestock breeding, as well as numerous trades and crafts, such asthe processing of wood, metal, bone and horn, textiles, leather, glass, ceramics, stone and other crafts. Ahoard of tools and items made of iron, bronze and lead, discovered inside the south-eastern corner towercomplex, was an important find illustrating the trades and crafts in Caričin Grad. It was a collective findconsisting of 44 items, the majority of which were broken, which suggests that they had been collected inorder to be melted down (fig. 17). The layer in which these items were unearthed was accurately datedfrom six specimens of coins from the period 565-578 during the reign of Emperor Justin II, which lendsparticular value to this find. Finds of defensive and offensive weapons point to the fundamental role playedby the Army, while numerous scales and weights clearly indicate the control of coins and the presence ofmoney-changers. In addition, the medical instruments found were also of particular importance.As it is impossible to describe all the finds here, we shall restrict ourselves to the most significant ones thatcorroborate what we already know about the material culture of the Early Byzantine period. The majority of the finds fall in the category of household items and utensils. First and foremost, theyincluded a large number of iron tools used for building houses, fences and other facilities, for instance,nails, clamps, braces and so on. There were also a large number of locks, bolts, padlocks and other objects(fig. 18, 1-2). Numerous finds can be associated with personal equipment (fig. 18, 3-9). People relied on natural daylight for lighting their houses, as evidenced by the abundance of pieces ofwindow panes that were grouped together in certain spots within the layers. The find of a small glass panewith gold leaf inserts is worthy of particular mention. This was a pane with rectangular inlays of gold leafarranged around the edges and which, in the central part, formed the contours of a cross. This item wasbrought to the residential quarter from one of the numerous basilicas in the city.Various objects intended for lighting occupied an important place in the repertoire of finds, such as poly-candela and bronze, ceramic, and glass lamps, of which there were a remarkable number (fig. 18, 11-12).

21Byzanz – das Römerreich im Mittelalter · Daim/Drauschke

19 Janakievski, Mikrostambena celina 40-67.

The most important discovery of this kind was a completely preserved bronze lamp with three spouts. Itshould be emphasised that the lamp was repaired twice, which testifies to its value.There was a large number of glass receptacles among the collected objects that made up the usual reper-toire of household goods, besides pots. The pottery items consisted mainly of locally produced ceramics,while imported pottery was rare. Nevertheless, there were significant finds of African sigillata, as well asfinds from Asia Minor. Besides parts of metal and bronze vessels, we also found, for instance, the fragmentof a large dish on a stand with two handles, of the kind with which we are familiar from the necropolis ofthe Great Migration, in Viminacium (dist. Braničevo, SRB) (fig. 18, 10) 20.Numerous finds of tools, such as hoes, picks, sickles and other items, indicate that agriculture played animportant role in the economic activities of the population of Caričin Grad (fig. 19, 1-5). Livestock breedingwas another aspect of agriculture, as evidenced by the large number of cowbells and by the bones ofdomestic animals, while finds of fish-hooks prove that fishing was another occupation. Trades were alsoimportant to the economy; these included the processing of wood and stone, hence the finds of axes forcutting wood, saws, chisels and planes, etc. There were tools for manufacturing textiles and leather, for

22 V. Ivanisevic · Caričin Grad – the Fortifications and the Intramural Housing in the Lower Town

20 Ivanišević / Kazanski / Mastykova, Viminacium 47 fig. 48 pl. 15, 10.

Fig. 17 Collective find of tools and objects of iron, bronze and lead from Caričin Grad.

Fig. 18 Findings from the intramural housing from Caričin Grad: 1 Iron lock. – 2 Iron key. – 3 Bronze strap-ends. – 4 Iron belt tab. –5 Bronze ring. – 6 Bronze earring. – 7 Bronze cross. – 8 Bone belt buckle. – 9 Bronze belt buckle. – 10 Bronze vessel fragment. – 11 Ceramic lamp. – 12 Bronze lamp. – Scale = 2:3.

making jewellery, bone and horn items, and for producing glass. These were just some of the crafts inwhich the artists in the residential quarter were engaged.The numerous fragmented moulds are evidence of jewellery making. Two of these moulds used for castingfibulae are worthy of particular mention, as well as the incomplete cast of a fibula of the same type (fig. 19,6-7), which was widespread throughout all the northern Balkans and the Danube River Basin21. Based onmaps, their distribution and the fact that one workshop was identified in Drobeta (dist. Mehedinţi, RO),Gabrovo (BG), Šumen (BG) and Venčan (dist. Provadia, BG)22, these fibulae are believed to have been usedmainly in the forts along the Danubian limes. However, for the first time, their production has now alsobeen confirmed in an urban centre in the interior of the Dacian diocese.In addition to casting, other techniques, such as beating, were also used to make jewellery. The find of amatrix for producing strap-ends illustrates this (fig. 19, 8). Two of the strap-ends were decorated with so-called tamga. These finds once again confirmed that some objects, which we established to be character-istic of a nomadic civilisation, belonged to the Byzantine cultural circle.Goods made of bones and horn represented another type of handicraft and the many finds of semi-prod-ucts made of horn, primarily from deer antlers, were evidence of this (fig. 19, 9).The remains of a workshop for manufacturing glass, discovered beside the Lower Town’s south-easterntower, are probably an important find. In addition to these remains that attest to glass manufacturing,there are finds of numerous chunks of yellow-green glass, unearthed in the facility beside the tower on thewestern defence wall.Weaponry also featured in the finds and included fragments of helmets, numerous arrowheads and speartips, frequent finds of small plating from armour, the handles and umbos of shields and, in particular,numerous pieces of horn from archers’ bows (fig. 19, 10-13). Finds of fragments of the Baldenheim type ofhel met are particularly important. It is known that this type of helmet was not rare in Caričin Grad23. Espe-cially important are the finds of fragments of the same helmet that came from two different places, besidethe western defence wall, and from the western portico of the street; from these finds, we were consequentlyable to partly reconstruct the helmet. It includes two curved bronze strips, one of which was found with alower frieze and the other, attached to the central plating of the crown, on which a hunting scene was en -gra ved. The parts of the helmet were made of gold-plated bronze, while the rivets were made of silver, orsil ver and lead. This specimen presented a new variety of curved, bronze strips in the shape of the letter »T«,with an accentuated, profiled browband between the shell of the helmet and the cheek flaps (fig. 20, 1).The second object of a military nature was an iron stirrup that, although slightly deformed, was fully pre -served (fig. 20, 2). The stirrup discovered was similar to a specimen found earlier in Caričin Grad24, butsmal ler. The discovery of one more stirrup in Caričin Grad indicates that these were not rare items but werethe usual repertoire of the Byzantine cavalry, which is mentioned in the Strategikon of Pseudo-Maurice25.Both the significance and the presence of cavalry in the region of Caričin Grad is demonstrated, amongother things, by the large number of specimens of bits, unearthed in the area of the residential quarter(fig. 20, 3).

25Byzanz – das Römerreich im Mittelalter · Daim/Drauschke

21 Uenze, Fibeln 483-494. 22 Măgureanu, Fibulele 110-111 figs 18-19.23 Vogt, Spangenhelme 200-203. – Bavant / Ivanišević, Ivstiniana

Prima 72 no. 49.

24 Kondić / Popović, Caričin Grad 212; 407 no. 105 pl. XXVIII.25 Lazaris, Étrier 277-278.

Fig. 19 Findings from the intramural housing from Caričin Grad: 1 Iron trowel. – 2 Iron axe. – 3 Iron adze. – 4 Iron saw. – 5 Ironhook. – 6 Ceramic mould. – 7 Cast of a bronze fibula. – 8 Bronze matrix. – 9 Horn instrument. – 10-11 Iron arrowheads. – 12 Ironplating from armour. – 13 Archers’ bow fragment. – 1-4 scale = 1:3; 5-13 scale = 2:3.

Finally, we should like to mention the numerous finds of coins (335 specimens), which will help to date theensembles discovered with greater accuracy, as well as to provide a better understanding of the circulationof coins in the central parts of Illyricum. The considerable number of finds of scales and weights (fig. 20,4-5) also indicate the importance of the monetary economy. We single out two specimens of these thatare made of glass. One of the specimens unearthed was green. It was circular with a profiled rim, markedon one side with a Greek monogram that read as »Genadios«. This kind of material is being discoveredmore and more often in Asia Minor and the Balkans, while most finds come from Egypt. Our weight is testi-mony to the central administration’s firm organisational control of the city. The functionary indicated bythe monogram may have been the prefect of Constantinople during the early years of Heraclius’ reign.The archaeological exploration of the fortification and of the residential quarter in the Lower Town offeredimportant data about the urbanisation, architecture and material culture of Caričin Grad and centralIllyricum in the proto-Byzantine epoch. After a comprehensive analysis of the remains of the architectureand finds, important data will be available about the appearance of the fortification, the streets and por ti -cos, as well as concerning the buildings erected in the residential area. The information about the natureof the settlement, the profile of the population and its economic activities will be of particular importance.All of this should offer a clearer insight into the social and economic life, not only of Caričin Grad but alsoof the region of northern Illyricum, in the period of the 6th and the beginning of the 7th centuries.

REFERENCES

27Byzanz – das Römerreich im Mittelalter · Daim/Drauschke

Fig. 20 Findings from the intramural housing from Caričin Grad: 1 Gold-plated bronze helmet. – 2 Iron stirrup. – 3 Iron bit. – 4 -Bronze weight. – 5 Bronze scale. – Scale = 2:3.

Sources

Novellae: Novellae. In: R. Schoell / G. Kroll (eds), Corpus Iuris Civilis3 (Berlin 1895).

John of Antioch, Chronici Fragmenta: Th. Mommsen, Bruchstückedes Johannes von Antiochia und des Johannes Malalas. Hermes6/3, 1872, 321-383.

Procope, De aedif.: Procopii Caesarensis De Aedificiis. Edited byJ. Haury (Leipzig 1913).

Literature

Bavant, Caričin Grad: B. Bavant, Caričin Grad and the Changes inthe Nature of Urbanism in the Central Balkans in the Sixth Cen-tury. In: A. G. Poulter (ed.), The Transition to Late Antiquity onthe Danube and Beyond. Proceedings of the British Academy141 (Chippenham 2007) 337-374.

Bavant, Identification: B. Bavant, Identification et fonction des bâti-ments. In: B. Bavant / V. Kondić / J.-M. Spieser (eds), CaričinGrad 2: Le quartier sud-ouest de la Ville Haute. Collection de l’École française de Rome 75 (Belgrade, Rome, 1990) 123-160.

Bavant / Ivanišević, Ivstiniana Prima: B. Bavant / V. Ivanišević, Ivsti -niana Prima – Caričin Grad (Beograd 2003).

Duval, Architecture: N. Duval, L’architecture religieuse de TsaritchinGrad dans le cadre de l’Illyricum oriental au VIe siècle. In: Villeset peuplement dans l’Illyricum protobyzantin [Actes du colloque

organisé par l’École française de Rome]. Collection de l’Écolefrançaise de Rome 77 (Rome 1982) 399-480.

Ivanišević / Kazanski / Mastykova, Viminacium: V. Ivanišević / M.Ka zanski / A. Mastykova, Les nécropoles de Viminacium à l’épo -que des Grandes Migrations. Centre de Recherche d’Histoire etCivilisation de Byzance, CNRS, Collège de France, Monographie22 (Paris 2006).

Janakievski, Mikrostambena celina: T. Janakievski, Docnoantičkamikrostambena celina nad teatrot vo Heraclea Lyncestis (Bitola2001).

Kondić / Popović, Caričin Grad: V. Kondić / V. Popović, CaričinGrad, utvrđeni grad u vizantijskom Iliriku. Caričin Grad, site for-tifié dans l’Illyricum byzantin (Beograd 1977).

Lazaris, Étrier: S. Lazaris, Considérations sur l’apparition de l’étrier:contribution à l’histoire du cheval dans l’Antiquité tardive. In: A.Gardeisen (ed.), Les Equidés dans le monde méditerranéenantique (Latte 2005) 275-288.

Măgureanu, Fibulele: A. Măgureanu, Fibulele turnate romano-bizan tine. Materiale şi cercetări de arheologice 4, 2008, 99-155.

Popović, Desintegration: V. Popović, Desintegration und Ruralisa-tion der Stadt im Ost-Illyricum vom 5. bis 7. Jh. n.Chr., In: D.Papenfuss / V. M. Strocka (eds), Palast und Hütte. Beiträge zumBauen und Wohnen im Altertum von Archäologen, Vor- undFrühgeschichtlern (Mainz 1982) 545-566.

Poulter, Transition: A. G. Poulter, The Transition to Late Antiquity.In: A. G. Poulter (ed.), The Transition to Late Antiquity on the

Danube and Beyond. Proceedings of the British Academy 141(Chippenham 2007) 1-50.

Sodini, Archaeology: J.-P. Sodini, Archaeology and Late Antique So -cial Structures. In: L. Lavan / W. Bowden (eds), Theory and Prac -tice in Late Antique Archaeology (Leiden, Boston 2003) 25-56.

Uenze, Fibeln: S. Uenze, Gegossene Fibeln mit Scheinumwicklungdes Bügels in den östlichen Balkanprovinzen. In: G. Kossack / S.Ulbert, Studien zur vor- und frühgeschichtlichen Archäologie[Fest schrift J. Werner]. Münchner Beiträge zur Vor- und Früh -geschichte (München 1974) 483-494.

Vogt, Spangenhelme: M. Vogt, Spangenhelme. Baldenheim undverwandte Typen. Kataloge Vor- und Frühgeschichtlicher Alter -tümer 39 (Mainz 2006).

28 V. Ivanisevic · Caričin Grad – the Fortifications and the Intramural Housing in the Lower Town

ILLUSTRATIONS REFERENCE

Figs 1-20 Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade.

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG / ABSTRACT / RÉSUMÉ

Caričin Grad erstreckt sich über ein Gebiet von etwa 20ha. Der zentrale Bereich entspricht dem urbanen Kerngebiet(Ausdehnung 8ha) mit der Akropolis, der Ober- und Unterstadt. Dieser Komplex ist von einem ausgedehnten Sied-lungsbereich umgeben, der wiederum von einem Verteidigungswall mit Palisade be grenzt wird. Die Unterstadt nahm eine besondere Stellung in der Struktur der Stadt ein. Hier findet sich eine Bebauung mit Wohn-und Wirtschaftseinheiten, was im Kotrast steht zu den übrigen offiziellen Gebäuden. Die For schungs er geb nisse derletzten zwei Jahrzehnte deuten an, dass die Besiedlung der Flächen innerhalb der Stadt mauern bereits unter JustinianI. begonnen hatte. Das besagte Viertel entwickelte sich in einem Be reich, der bis dahin ungenutzt geblieben war, oderum genauer zu sein, in Bereichen, wo die Errichtung öffent licher Gebäude begonnen hatte; diese aber nie abge-schlossen worden war. Ebenso wichtig ist die Frage, wann in der Unterstadt die Verteidigungsmauern und der Großteil der übrigen Struk turenerrichtet wurden. Die Resultate der archäologischen Ausgrabungen haben gezeigt, dass die Be fes ti gung der Unterstadtgemeinsam mit der Errichtung der Verteidigungsmauern der Oberstadt Be stand teil einer groß angelegten Bau -kampagne war und die erste Bebauungsphase darstellt. Die im Südwest-Teil der Unterstadt ausgegrabenen Befunde können in mehrere chronologische Phasen un ter teiltwerden. Die sogenannte Baracke, ein rechteckiges Gebäude, in der die Bauarbeiter für die Ver teidigungsmauern unter-gebracht waren, datiert in die erste Phase. Ein größeres, eindeutig öffentliches Gebäu de (Stallungen?) wird aufgrundtechnologischer Anhaltspunkte (Steinmauerwerk mit Kalkmörtel) in die zweite Phase datiert. Dieser Gebäudetyp ist dereinzige seiner Art in diesem Bereich. In die dritte und wich tig ste Phase datieren die Bauten neben dem westlichenPortikus und entlang des westlichen Verteidigungs walles. Es handelt sich um zweireihige Strukturen mit Mauern ausStein, Holz und Rutengeflecht. Diese Bauten unterscheiden sich grundlegend von jenen der ersten beiden Phasen. Dievierte und letzte Phase ist durch geringfügige architektonische Eingriffe und Anbauten an die bereits bestehendenGebäude gekenn zeichnet.Die Untersuchungen des Wohnbereichs der Unterstadt brachten eine große Zahl an archäologischen Arte faktenzutage. K. K.

Caričin Grad extends over an area of about 20ha, the principal part of which was the city core covering an area of8ha and that encompassed three entities: the Acropolis, the Upper and the Lower Town. Spacious suburbs surroundedby a palisade defence wall stretched out on the slopes around this complex. The Lower Town with its public facilities occupied a special place in the city planning. It had intramural housing, whichpresented a contrast to the official buildings. Judging by the research results from the intramural housing revealedduring the last two decades, the process of settlement inside the city walls had already commenced during the reign

of Justinian I. The said quarter developed in the area that had not been urbanised or, to be more precise, in the spaceswhere the construction of public buildings had commenced but had never been fully completed. An equally important question arising from the investigation of the Lower Town was exactly when the defence wallsof the Lower Town and the majority of structures actually came into being. Excavations have shown that the construc-tion of the fortifications of the Lower Town was part of a unified construction opera tion and, along with the construc-tion of the defence walls of the Upper Town, was part of the first phase in the building of the city. The structures unearthed in the south-western quarter of the Lower Town can be attributed to several chronologicalphases. A rectangular building described as the »barracks« where the builders of the defence wall were housed waspart of the earliest phase. A larger, definitely public building (stable?), the only one of its kind in this area, belongedto the second phase and was made of stone bonded with lime mortar. A row of structures with walls of stone, timberand cob, erected in two rows, one beside the western portico and the other next to the western defence wall,belonged to the third, most important phase. These structures completely negated the structural principles of the firsttwo phases. As part of a final, fourth stage, minor alterations were made to buildings in the form of the addition ofnew premises to the existing buildings. The exploration of the residential quarter in the Lower Town revealed a vast number of items of material culture.

Caričin Grad s’étend sur une superficie d’environ 20ha. La zone centrale correspond au cœur urbain d’une étenduede 8ha comportant l’acropole, la ville haute et la ville basse. Ce complexe est entouré de vastes faubourgs palissadés. La ville basse avec son infrastructure publique occupait une place particulière dans la structure de la ville. Elle incluaitdes unités d’habitation et de commerce qui contrastent avec les bâtiments officiels. Les résultats des recherchesmenées au sujet de la ville basse durant les deux dernières décennies révèlent que l’occupation de l’espace à l’intérieurde l’enceinte avait déjà commencé sous le règne de Justinien Ier. Ledit quartier se développa dans un secteur jusque-là inutilisé, ou plus précisément sur des surfaces où l’édification de bâtiments publics avait commencé, mais n’avaitjamais été achevée.Tout aussi importante est la question de savoir quand ont été édifiés les murs d’enceinte de la ville basse et la majeurepartie des autres structures. Les fouilles archéologiques ont démontré que la fortification de la ville basse faisait partied’une campagne de construction de grande envergure qui comprenait également l’édification de l’enceinte de la villehaute. Il s’agit de la première phase de construction. Les structures mises à jour dans le sud-ouest de la ville basse peuventêtre attribuées à plusieurs phases chronologiques. Un bâtiment de plan rectangulaire, surnommé la baraque, danslaquelle étaient logés les ouvriers responsables de l’enceinte, a été érigé durant la première phase de construction. Unédifice plus grand, de toute évidence un bâtiment public (écuries), appartient à la seconde phase de construction. Cetype d’édifice est le seul de son genre dans cette zone. Il est construit en pierre avec du mortier à base de chaux. Lesédifices qui se trouvent à côté du portique occidental et qui longent l’enceinte occidentale sont disposés en deuxrangées et appartiennent à la troisième phase de construction qui est la plus importante. Ces bâtiments dont les murssont faits de pierre, de bois et de torchis, se distinguent fondamentalement de ceux des deux phases antérieures. Laquatrième et dernière phase est marquée par des modifications mineures survenues sur des bâtiments antérieurs sousforme d’annexes.L’exploration du quartier résidentiel de la ville basse révéla un grand nombre d’artefacts archéologiques. A. S.

Dr. Vujadin IvaniševićArheološki InstitutKnez Mihailova 35/IVSRB - 11000 [email protected]

29Byzanz – das Römerreich im Mittelalter · Daim/Drauschke

TEIL 1 WELT DER IDEEN, WELT DER DINGE

BYZANZ – DAS RÖMERREICH IM MITTELALTER

VERZEICHNIS DER BEITRÄGE

WELT DER IDEEN

Ernst KünzlAuf dem Weg in das Mittelalter: die Gräber Constantins,Theoderichs und Chlodwigs

Vasiliki TsamakdaKönig David als Typos des byzantinischen Kaisers

Umberto RobertoThe Circus Factions and the Death of the Tyrant: John of Antioch on the Fate of the Emperor Phocas

Stefan AlbrechtWarum tragen wir einen Gürtel? Der Gürtel der Byzantiner – Symbolik und Funktion

Mechthild Schulze-DörrlammHeilige Nägel und heilige Lanzen

Tanja V. KushchThe Beauty of the City in Late Byzantine Rhetoric

Helen PapastavrouClassical Trends in Byzantine and Western Art in the 13th and 14th Centuries

WELT DER DINGE

Birgit BühlerIs it Byzantine Metalwork or not? Evidence for Byzantine Craftsmanship Outside the Byzantine Empire(6th to 9th Centuries AD)

Isabella Baldini LipolisHalf-crescent Earrings in Sicily and Southern Italy

Yvonne PetrinaKreuze mit geschweiften Hasten und kreisförmigenHastenenden

Anastasia G. YangakiThe Scene of »the Holy Women at the Tomb« on a Ringfrom Ancient Messene and Other Rings Bearing theSame Representation

Ellen RiemerByzantinische und romanisch-mediterrane Fibeln in der Forschung

Aimilia YeroulanouCommon Elements in »Treasures« of the Early ChristianPeriod

Tivadar VidaZur Formentwicklung der mediterranen spätantik-frühbyzantinischen Metallkrüge (4.-9. Jahrhundert)

Anastassios AntonarasEarly Christian and Byzantine Glass Vessels: Forms and Uses

Binnur Gürler und Ergün LafliFrühbyzantinische Glaskunst in Kleinasien

Ronald BockiusZur Modellrekonstruktion einer byzantinischen Dromone(chelandion) des 10./11. Jahrhunderts im Forschungsbereich Antike Schiffahrt, RGZM Mainz

Isabelle C. Kollig, Matthias J. J. Jacinto Fragata und KurtW. AltAnthropologische Forschungen zum ByzantinischenReich – ein Stiefkind der Wissenschaft?

KONSTANTINOPEL / ISTANBUL

Albrecht BergerKonstantinopel – Gründung, Blüte und Verfalleiner mediterranen Metropole

Rudolf H.W. StichelDie Hagia Sophia Justinians, ihre liturgische Einrichtungund der zeremonielle Auftritt des frühbyzantinischenKaisers

Helge SvenshonDas Bauwerk als »aistheton soma« – eine Neu inter -pretation der Hagia Sophia im Spiegel antiker Vermessungslehre und angewandter Mathematik

Lars O. Grobe, Oliver Hauck und Andreas Noback Das Licht in der Hagia Sophia – eine Computersimulation

Neslihan Asutay-EffenbergerDie justinianische Hagia Sophia: Vorbild oder Vorwand?

Örgü DalgıçThe Corpus of Floor Mosaics from Istanbul

Stefan AlbrechtVom Unglück der Sieger – Kreuzfahrer in Konstantinopelnach 1204

Ernst Gamillscheg Hohe Politik und Alltägliches im Spiegel des Patriarchatsregisters von Konstantinopel

AGHIOS LOT / DEIR ‘AIN ‘ABATA

Konstantinos D. PolitisThe Monastery of Aghios Lot at Deir ‘Ain ‘Abata in Jordan

ANAIA / KADIKALESİ

Zeynep MercangözOstentatious Life in a Byzantine Province: Some Selected Pieces from the Finds of the Excavation in Kuşadası, Kadıkalesi/Anaia (Prov. Aydın, TR)

Handan ÜstündağPaleopathological Evidence for Social Status in a Byzan-tine Burial from Kuşadası, Kadıkalesi/Anaia: a Case of»Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis« (DISH)

ANDRONA / AL ANDARIN

Christine StrubeAl Andarin, das antike Androna

Marlia Mundell MangoAndrona in Syria: Questions of Environment and Economy

AMORIUM / HISARKÖY

Christopher S. LightfootDie byzantinische Stadt Amorium: Grabungsergebnisse der Jahre 1988 bis 2008

Eric A. IvisonKirche und religiöses Leben im byzantinischen Amorium

Beate Böhlendorf-ArslanDie mittelbyzantinische Keramik aus Amorium

Edward M. SchoolmanKreuze und kreuzförmige Darstellungen in der Alltagskultur von Amorium

Johanna WitteFreizeitbeschäftigung in Amorium: die Spiele

CHERSON / SEWASTOPOL

Aleksandr AjbabinDas frühbyzantinische Chersonesos/Cherson

Adam Rabinowitz, Larissa Sedikova und Renata HennebergDaily Life in a Provincial Late Byzantine City: Recent Multidisciplinary Research in the Southern Region of Tauric Chersonesos (Cherson)

Tatjana JašaevaPilgerandenken im byzantinischen Cherson

EPHESOS / SELÇUK

Sabine LadstätterEphesos in byzantinischer Zeit – das letzte Kapitel der Geschichte einer antiken Großstadt

TEIL 2 SCHAUPLÄTZE

Andreas KülzerEphesos in byzantinischer Zeit – ein historischer Überblick

Andreas PülzDas Stadtbild von Ephesos in byzantinischer Zeit

Martin SteskalBadewesen und Bäderarchitektur von Ephesos in frühbyzantinischer Zeit

Gilbert WiplingerDie Wasserversorgung von Ephesos in byzantinischer Zeit

Norbert ZimmermannDie spätantike und byzantinische Malerei in Ephesos

Johanna Auinger und Maria AurenhammerEphesische Skulptur am Ende der Antike

Andrea M. Pülz und Feride KatByzantinische Kleinfunde aus Ephesos – ein Materialüberblick

Stefanie Wefers und Fritz MangartzDie byzantinischen Werkstätten von Ephesos

Manfred Koob, Mieke Pfarr und Marc GrellertEphesos – byzantinisches Erbe des Abendlandes Digitale Rekonstruktion und Simulation der Stadt Ephesos im 6. Jahrhundert

IUSTINIANA PRIMA / CARIČIN GRAD

Vujadin IvaniševićCaričin Grad – the Fortifications and the Intramural Housing in the Lower Town

KRASEN

Valery GrigorovThe Byzantine Fortress »Krasen« near Panagyurishte

PERGAMON / BERGAMA

Thomas OttenDas byzantinische Pergamon – ein Überblick zu Forschungsstand und Quellenlage

Manfred KlinkottDie byzantinischen Wehrmauern von Pergamon als Abbild der politisch-militärischen Situationen im westlichen Kleinasien

Sarah JappByzantinische Feinkeramik aus Pergamon

TELANISSOS / QAL’AT SIM’AN

Jean-Luc BiscopThe Roof of the Octagonal Drum of the Martyrium of Saint-Symeon

USAYS / ĞABAL SAYS

Franziska BlochÖllampenfunde aus dem spätantik-frühislamischen Fundplatz Ğabal Says im Steppengürtel Syriens

Franz Alto BauerByzantinische Geschenkdiplomatie

DER NÖRDLICHE SCHWARZMEERRAUM

Elzara ChajredinovaByzantinische Elemente in der Frauentracht der Krimgoten im 7. Jahrhundert

Rainer SchregZentren in der Peripherie: landschaftsarchäologische Forschungen zu den Höhensiedlungen der südwestlichen Krim und ihrem Umland

DER UNTERE DONAURAUM

Andrey AladzhovThe Byzantine Empire and the Establishment of the Early Medieval City in Bulgaria

Stanislav StanilovDer Pfau und der Hund: zwei goldene Zierscheiben aus Veliki Preslav

DER MITTLERE UND OBERE DONAURAUM

Jörg DrauschkeHalbmondförmige Goldohrringe aus bajuwarischen Frauengräbern – Überlegungen zu Parallelen und Provenienz

Péter ProhászkaDie awarischen Oberschichtgräber von Ozora-Tótipuszta (Kom. Tolna, H)

Falko Daim, Jérémie Chameroy, Susanne Greiff, Stephan Patscher, Peter Stadler und Bendeguz TobiasKaiser, Vögel, Rankenwerk – byzantinischer Gürteldekordes 8. Jahrhunderts und ein Neufund aus Südungarn

Ádám BollókThe Birds on the Braid Ornaments from Rakamaz: a View from the Mediterranean

Péter LangóCrescent-shaped Earrings with Lower Ornamental Band

Miklós TakácsDie sogenannte Palmettenornamentik der christlichenBauten des 11. Jahrhunderts im mittelalterlichen Ungarn

SKANDINAVIEN

John LjungkvistInfluences from the Empire: Byzantine-related Objects inSweden and Scandinavia – 560/570-750/800 AD

TEIL 3 PERIPHERIE UND NACHBARSCHAFT

Unter diesem Banner erscheint im Jahr 2010 eine Reihe von Publikationen des Verlages des