Post-Columbian environmental history of Lago Petén Itzá ... · del Lago Petén Itzá indica en...

Transcript of Post-Columbian environmental history of Lago Petén Itzá ... · del Lago Petén Itzá indica en...

Pérez et al.490

Post-ColumbianenvironmentalhistoryofLagoPeténItzá,Guatemala

Liseth Pérez1,*, Rita Bugja1, Julieta Massaferro2, Philip Steeb1, Robert van Geldern3, Peter Frenzel4, Mark Brenner5, Burkhard Scharf 1, and Antje Schwalb1

1 Institut für Umweltgeologie, Technische Universität Braunschweig, Langer Kamp 19c, 38106 Braunschweig, Germany.

2 CENAC-APN, CONICET, San Marín 24, Bariloche, 8400, Argentina.3 GeoZentrum Nordbayern, Angewandte Geowissenschaften, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg,

90518 Erlangen, Germany.4 Institut für Geowissenschaften, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, Burgweg 11, 07749, Jena, Germany.

5 Department of Geological Sciences & Land Use and Environmental Change Institute, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, 32611, USA.

ABSTRACT

Two ~40-cm-long sediment cores, PI-SC-1-10m and PI-SC-2-40m, were recovered at 10 and 40 m water depth, respectively, from Lago Petén Itzá, in the Department of Petén, northern Guatemala. The cores span the last ~525 years of sediment accumulation in the basin. This study explores lake level and trophic state changes that Lago Petén Itzá has experienced since European contact in the early 1500s. We inferred past environmental variability using changes in sediment geochemistry and fluctuations in relative species abundances of ostracode and chironomid fossil assemblages. Changes in concentrations of organic matter (OM), carbonate, total carbon (TC), total nitrogen (TN), C/N ratios, bromine (Br), and faunal relative abundances were used to infer changes in the trophic status of the lake. Cultural eutrophication began in the 1930s, and anthropogenic impact increased significantly after ~1970. Higher linear sedimentation rates, up to 9.1 mm yr-1, began recently. They are attributed to increases in riparian settlement, deforestation and associated land use changes, which led to accelerated soil erosion. An ostracode-based transfer function was applied to assemblages in core PI-SC-1-10m, which enabled us to identify periods when lake level fluctuated. Such historical fluctuations in lake levels were driven primarily by changes in rainfall. Past lake levels can be summarized as follows: (1) fluctuating, high lake levels from ~1550s to the 1730s and from the early 1940s to 2005, and (2) stable, lower lake levels from about 1750 to the early 1900s. Higher relative abundance of the ostracode Physocypria globula and higher rubidium (Rb) concentrations indicate higher lake levels than today. Chironomids also show sharp fluctuations along the cores that could be related to water level changes. The presence of chironomid assemblages Chironomus, Procladius, and Einfeldia from 1960–2000 AD shows high productivity levels. The Lago Petén Itzá sediment record indicates a generally arid Little Ice Age (LIA), with exceptions around 1580 and 1650 when high lake levels similar to those of the 20th century, i.e. ~5 m higher than today, indicate more humid conditions.

Key words: freshwater ostracodes, chironomids, lake level, geochemistry, eutrophication, Lago Petén Itzá, Guatemala.

Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, v. 27, núm. 3, 2010, p. 490-507

Pérez,L.,Bugja,R.,Massaferro,J.,Steeb,P.,vanGeldern,R.,Frenzel,.P,Brenner,M.,Scharf,B.,Schwalb,A.,2010,Post-ColumbianenvironmentalhistoryofLagoPeténItzá,Guatemala:RevistaMexicanadeCienciasGeológicas,v.27,núm.3,p.490-507.

Post-Columbian environmental history of Lago Petén Itzá, Guatemala 491

RESUMEN

Dos núcleos de sedimentos PI-SC-1-10m y PI-SC-2-40m de 40 cm de largo fueron extraídos bajo un tirante de agua de 10 y 40 m en el Lago Petén Itzá, Departamento de Petén, en el norte de Guatemala. Los núcleos abarcan los pasados ~525 años de acumulación de sedimentos en el lago. Este estudio explora los cambios en los niveles del lago y cambios en el estado trófico que el Lago Petén Itzá ha sufrido desde el contacto Europeo a inicios del siglo XVI. Hemos inferido la variabilidad ambiental del pasado utilizando cambios en la geoquímica de los sedimentos y en las fluctuaciones de las abundancias relativas de las especies de comunidades de ostrácodos y quironómidos. Cambios en las concentraciones de materia orgánica (MO), carbonato, carbono total (CT), nitrógeno total (NT), bromo (Br), en la proporción C/N y cambios en la abundancia relativa faunística fueron utilizadas para inferir cambios en el estado trófico del lago. La eutroficación cultural inició desde la década de 1930, y el impacto antropogénico ha aumentado significativamente desde ~1970. Una alta tasa de sedimentación linear de hasta 9.1 mm yr-1 ha iniciado recientemente. Esto se atribuye a un incremento en la ocupación ribereña del lago durante las últimas décadas, la cual está asociada a cambios de uso de la tierra y ha llevado a una acelerada deforestación y erosión de los suelos. Una función de transferencia basada en ostrácodos fue aplicada a las comunidades del núcleo PI-SC-1-10m pudiendo identificar períodos durante los cuales el nivel del lago ha fluctuado unos ~5 m. Estas fluctuaciones históricas en el nivel del lago fueron causadas principalmente por cambios en la precipitación pluvial. Los niveles pasados del lago se resumen de la siguiente forma: (1) niveles altos fluctuantes entre las décadas de 1550 y 1730 y de los primeros años de la década de 1940 a 2005, y (2) niveles bajos estables de 1750 a la década de 1900. Una abundancia relativa alta de Physocypria globula y altas concentraciones de rubidio (Rb) indican niveles del lago más altos a los actuales.

Quironómidos indican fluctuaciones a lo largo de los núcleos que pueden estar relacionadas con cambios en los niveles del lago. La presencia de las comunidades de quironómidos Chironomus, Procladius, y Einfeldia de 1960–2000 AD indica niveles altos de productividad. El registro sedimentario del Lago Petén Itzá indica en general una árida Pequeña Edad de Hielo (PEH), con excepción de los años alrededor de 1580 y 1650, cuando los niveles del lago fueron altos y similares a los del siglo XX, i.e., unos ~5 m más altos que los actuales, lo que indica condiciones más húmedas.

Palabras clave: ostrácodos lacustres, quironómidos, nivel del lago, geoquímica, eutroficación, Lago Petén Itzá, Guatemala.

INTRODUCTION

Climatechangeandanthropogenicimpactshaveaf-fectedneotropicalfreshwaterenvironmentsintheMayaLowlandsfor thousandsofyears(Curtiset al.,1998;Brenneret al.,2002;Rosenmeieret al.,2002,2004),mak-ingtheregionespeciallyinterestingforpaleolimnologists.PaleolimnologicalstudiesontheYucatánPeninsulahavefocusedonHolocene(Hodellet al.,1995;Curtiset al.,1996;Leydenet al.,1998)andPleistocenedeposits(Hodellet al.,2008),withrecentspecialattentiononthelatedegla-cial-earlyHolocenetransition(Hillesheimet al.,2005).Anumberofproxyvariableshavebeenutilizedtoinferpastclimateandenvironmentalchangesinthelowlandneotropi-calregion,includingpollen(Leyden,1987;Leydenet al.,1998;Islebeet al.,1996;Wahlet al.,2006;Hodellet al.,2008),gastropods,foraminifers,ostracodes(Hodellet al.,1995,2005;Curtiset al.,1996,1998;Rosenmeieret al.,2002),anddiatoms(Rosenmeieret al.,2004).Theoxygenandcarbonisotopiccompositionofcarbonateshellsofsedi-mentedgastropods,foraminifersandostracodescanbeusedtoinferpastlakeproductivityandprecipitation/evaporationratios(Brenneret al.,2002;Schwalb,2003).

Ostracodes(Crustacea:Ostracoda)arebivalvedcrus-

taceanswithlow-Mgcalciteshellsthatinhabitavarietyofaquaticenvironments.Ondeath,theirshellsaredepositedandcanbewellpreservedinlacustrinesediments(Smith,1993;Curtiset al.,1998;Holmes,1998;Dole-Olivieret al.,2000). Ostracode taxa have specific ecological requirements andtheknowledgeofmodernecologicalrequirementscanbeusedtoreconstructpastenvironmentalconditionswherefossilsarefound(ForesterandSmith,1994;Schwalb,2003;Scharfet al.,2005).RecentlimnologicalstudiesinMesoamericashowthattheostracodefaunaisabundant,diverse,andinfluencedbywaterdepthandassociatedphysico-chemicalcharacteristics(Pérezet al.,2010a,2010b,inpress).

Similar toostracodesanddiatoms,chironomids(Insecta:Diptera),ornon-bitingmidges,alsorespondrapidlytoenvironmentalchange,makingthempowerfulbioindicators.Chironomidsarepartofthefreshwater,ben-thicmacroinvertebratefauna.Theirlarvaehavechitinizedheadcapsules,whicharedepositedandpreservedinlakesediments(Massaferroet al.,2004;Verschurenet al.,2000).Therehavebeenanumberoftaxonomicandpaleolimno-logicalstudiesofchironomidsinNorthAmerica(Heinrichset al.,1999;LittleandSmol,2000;Woolleret al.,2004)andSouthAmerica(MassaferroandBrooks,2002;Massaferro

Pérez et al.492

numberofstudieshaveexploredthelake’smorphometryandlimnology(BrezonikandFox,1974;Deeveyet al.1980;Hillesheimet al.,2005;Anselmettiet al.2006;MARN-AMPI,2008;Pérezet al.,2010b).

FollowingEuropeancontactintheearly1500s,humanpopulationdensityinnorthernGuatemalaremainedlowforcenturies.In1964,thereportedpopulationinPeténwas~26,720inhabitants.Thereafter,therewasanabruptincreaseinpopulationthroughimmigrationdrivenbyagovernmentpolicythatprovidedlandandencouragedsettlementintheregion(PainterandDurham,1995;Rosenmeieret al.,2004).Acensusdonein2002(XICensoNacionaldePoblaciónyVIdeHabitación)reportedatotalpopulationof11,237,196inhabitantsinGuatemala,ofwhom366,735livedinPetén.ThepopulationofFlores,theripariancapitalcityoftheDepartmentofPetén,was30,807(INE,2002).Populationgrowthintownsaroundthelakeappearstobechangingthelake’strophicstate.

Inadditiontoeutrophication,documentedrapidlakelevelchangesareanotherchallengeforlakesidedwellers.Stage fluctuations in Petén Itzá have evidently been a part ofthelake’shistorysincethelatePleistocene(Anselmettiet al., 2006). Recently, high lake level stands have flooded shorelineproperties,forcingsomeresidentstoabandontheirhomes.HighprecipitationisthemaincauseofincreasedlakelevelstandsinLagoPeténItzá.InJune2008,Peténreceivedheavyrainfallandseveraltowns,includingSanBenito and Santa Ana, experienced severe flooding that causedtemporaryevacuationofinhabitants(Escobar,2008).1938wasapparentlytheyearofhighestannualprecipita-tion(2600mm)inthelastcentury,andtheconsequentriseinlakeleveliscommemoratedbyaplaqueonthewallof

et al.,2005),however,thechironomidfaunaofthenorth-ernlowlandneotropicsremainslargelyunexplored.OnlyafewtaxonomicandecologicalstudieshavebeendoneinCentralAmericaandtheCaribbeanregion(Coffmanet al.,1992;WatsonandHeyn,1992;VinogradovaandRiss,2007;Woolleret al.,2007).

Ostracodeandchironomidcommunitiesreactrapidlytoclimateandenvironmentalchanges,makingthemreliableindicatorsofpastlimnologicalconditions(MourguiartandCarbonel,1994).Theycanbeusedtoinferpastwaterqualityandtrophicstatus(Smith,1993;Nazarovaet al.,2008),changesinprecipitationandsedimentlithology(Scharf,1998;MassaferroandBrooks,2002),andothercharacteristicsofthewatercolumn,includingpH,temperature,conductivity,depth(BrooksandBirks,2004;Mischkeet al.,2010),andsalinity(Heinrichset al.,1999).

STUDY AREA

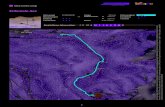

LagoPeténItzáliesabout110ma.s.l.,hasasurfacearea~100km2,andamaximumdepth~160m.ThelakeislocatedintheCentralPeténLakeDistrictofnorthernGuatemala(16°55’N,89°50’W)(Figure1).TheCentralPeténLakeDistrictislocatedinthesedimentarybasinoftheMayablockontheNorthAmericanplate.ThesouthernmostextentoftheYucatánPeninsulaisunderlainbyCretaceouscarbonates(Anselmettiet al.,2006).LagoPeténItzáisoligo-mesotrophic,butbegantoexperienceanthropogenicimpactsinthelastfewdecades.Today,lakewatershaveadissolvedionconcentrationof~11meqL-1andaredomi-natedbycalcium,magnesium,sulfate,andbicarbonate.A

Figure 1. Study area in central Petén Lake District (black scale), northern Guatemala (modified from Google Earth 2010), and Lago Petén Itzá (indicated bythewhitearrowandwithcorrespondingblackandwhitescalebar)showingthelocationwhereshortcoresPI-SC-1-10mandPI-SC-2-40mwereretrieved.

Post-Columbian environmental history of Lago Petén Itzá, Guatemala 493

Description PI-SC-1-10m PI-SC-2-40m

CoordinatesLatitudeN 16°59.29’ 16°59.17’LongitudeW 89°50.46’ 89°43.32’

Water depth 10m 40m

Description of site of recovery

Southern part of thelake.Shallowseasonalswampyzone.

Easternpartofthelake.Close to villages, andtributaryriverIxlú.

Core lengthDating 38cm 38cmGeochemistryanalyses 38cm 40cmBioindicatoranalyses

-Ostracodes 36cm 40cm-Chironomids 36cm 42cm

Estimated age 488years 135years

Mean sedimentation rate

0.89mmyr-1 4.3mmyr-1

Sediment description Lightolivegrayclayeysilts

Darkolivegrayclayeysilts

Type of analysisBioindicators

-Ostracodes + +Speciesincore 7 6

-Chironomids + +Speciesincore 8 37

Geochemistry-LOI + +-C:Nratio + +-Mainelements + +-Traceelements + +

Table1.Descriptionofthetwoshortcoresanalyzedinthisstudy.abuildinginFloresthatindicatesthehigh-watermark.Anecdotalaccountsoflakelevelchangeforthelastcen-turysuggestithasrangedbyasmuchas8m.Thereare,however,nopublishedrecordsoflakelevelchangeinPeténItzáspanningaperiodlongerthanthreeyears(MARN-AMPI,2008).TheInstitutoNacionaldeVulcanología,Sismología,MetereologíaeHidrología(INSIVUMEH,1985)reportedmonthlyrainfallandstagechangeinLagoPeténItzáandotherregionalwaterbodiesfortheperiod1982-1985.Priortothattime,rainfallandlakelevelrecordsareevenscarcer(Deeveyet al.,1980).Alternativesourcesofinformationarerequiredtoreconstructpastlakelevelandclimatehistory.

Waterlevelchangesinlakesareoftencausedbyclimatechanges,i.e.shiftsintherelativeamountofprecipitationtoevaporation.Inturn,suchalterationsinlakeleveltriggerchangesinostracodeandchironomidcommunities.Thesefaunalchangesarefrequentlypreserved in lacustrinesediments.LagoPeténItzáisatropicalclosed-basinlakeanditssedimentrecordhasproventobeahighlysensitiverecorderofchangesinthebalancebetweenprecipitationandevaporation(Hodellet al.,2008).Inthisstudy,weusedfaunalchangesofostracodeandchironomidassemblages,aswellasshiftsingeochemistryinsedimentcores,toinferpastchangesinthetrophicstateandwaterlevelinthebasinoverthepast~525years.

METHODS

Twoshortsedimentcores,PI-SC-1-10mandPI-SC-2-40m,wereretrievedfrom10mand40mwaterdepth,respectively,inLagoPeténItzá(Figure1).ThecoreswerecollectedwithanUWITEC-gravitycorerusing60-cm-long,transparentPVCtubes.Locationofcollectionsites,corelengths,age,sedimentationrates,andvariablesanalyzedarefoundinTable1.Chironomidsandostracodeswereanalyzedinbothcores.Inadditiontothecorescollectedforfaunalremains,twoparallelcoreswereretrievedfor210Pbdating,andanothertwocoresweretakenforgeochemicalanalysis.Shortcoresweresectionedat2-cmintervalsforbioindicatoranalysis.Shortcorestakenforgeochemicalanalysisanddatingweresectionedat0.5-cmintervalsabove20cmdepth,andat1-cmintervalsbelowthatdepth.Bydoingthisweachievedgooddatingresolutionintheupperpartofbothshortcores.AnUWITECcorecutterwasusedforsectioningsedimentcores.AllsampleswerepackedinWhirl-pack®bagsandkeptunderrefrigeration.

Initialsedimentdescriptionwasmadeonwholecores.Color,texture,odorandothercharacteristicsweredescribedfromsedimentsamples.ColorwasdeterminedwithaRockColorChart(GeologicalSocietyofAmerica)withMunsellcolorchips.Mülleret al.(2009)reportedonthelithologiccompositionofsurfacesedimentstakenalongawater-depthtransectinLagoPeténItzá.

Priortogeochemicalandchronologicalmeasure-

ments,wetsedimentsampleswerehomogenizedusingasmallspatula.Watercontentwasdeterminedbyweighingsamplesbeforeandafterovendryingat105°Cfor24hours(DIN/18121-1;DIN,1998).Organicmatter,carbonate(CO2weightloss)andnon-carbonateinorganicmatter(clastics)weremeasuredbyloss-on-ignition(LOI)asdescribedinHeiriet al. (2001). Dried samples were pulverized to a fine powderwithanelectronicballmill.WeusedX-raydiffrac-tion(XRD)todeterminequalitativelythemainmineralsintheshortcoresediments.TheelementsFe,Sr,Br,Cu,Zn,Rb, Zr, Y, and Pb were quantified using energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometry (Cheburkin et al.,1997).ZrandPbcouldnotbedeterminedincorePI-SC-1-10m.TotalC,N,andSmeasurementsweremadewithanelementalanalyzer(HEKAtechGmbH,EuroEA3000)byoxidativecombustionat1000°C,gas-chromicsepara-tionofgasesandthermalconductivitydetection.OrganiccarbonandtotalnitrogencontentwereusedforcalculationofC/Nratiosinshortcores.AllgeochemicalanalysesweredoneattheInstitutfürUmweltgeologie(IUG),TechnischeUniversitätBraunschweig,Germany.

For210Pbdating, dry,weighedpulverizedsampleswerestoredinsealedvialsatroomtemperatureforfourweeks.Analysisforradioisotopes(210Pb,214Pb,and137Cs)

Pérez et al.494

wasmadebydirectgammaspectroscopyusingalow-backgroundgammaspectrometer(AmetekORTECandCanberraEurisys)withahigh-puritygermaniumwell-de-tector.MeasurementsweremadeattheGeochronologie&IsotopenhydrologieSektion,Leibniz-InstitutfürAngewandteGeophysik(LIAG),Hannover,Germany.Unsupported210Pbactivitywascalculatedforallmeasureddepthsthroughouttheshortcores.TheConstantSedimentationRateModel(CSR)wasusedtodeterminethesedimentages.Themodelassumesthatinitialconcentrationandsedimentationratearebothconstant,andnopost-depositionalmixingoccurred(Robbins,1978;Laissaouiet al.,2008).210Pbdatingcanonlybeappliedreliablytodatesedimentsofthelast~110years,thuswecalculatedinbothshortcoresthemeanmassaccumulationrate(MAR,kgm-2yr-1) for the first 100 yearsandusedittoinferagesdeeperinthecore.MARwasestimatedbyalinearregressionofthelogexcess210Pbactivitiesateachdepthagainstlinearaccumulatedsedimentmass/area(kgm-2).Theanthropogenicradioisotope137Cs,whichcansometimesbeusedtoidentifythe1963atmo-sphericbomb-testingpeak,wasalsomeasuredandusedasacomplementarychronologicalmarker.

Weenumeratedvalvesandcarapacesofadultos-tracodesinthe2-cmwetsedimentslices.Two1g(wet)aliquots were separated from each sample. The first aliquot waswashedintoasmall(10cmdiameter),63µmmeshsieve.Allostracodeswereseparatedandcountedinthissample.Thesecondaliquotwasanalyzedforwatercontent,usingthesamemethodappliedtosamplesforgeochemicalanalysis. Ostracodes were separated using fine brushes and enumeratedinagriddeddishusingaLeicaMZ7.5stereo-microscope.Ostracodeabundanceispresentedasvalvesorcarapaces per dry mass sediment. Identification followed Pérezet al.(2010a),andpaleoenvironmentalinterpretationreliedonmodernostracodeecologicaldatareportedbyPérezet al.(2010b).

Subfossilchironomidswereanalyzedinwet,2cmsedimentslices.Asmallsubsample(<3g)ofwetsedimentfrom each sample was deflocculated in 10 % KOH, heated to70°Cfor10min,andlaterheatedinwaterto90°Cfor20min.Sedimentswerethensievedusing212µmand95µm mesh sieves. A Bogorov sorting tray and fine forceps wereusedtoseparatelarvalchironomidheadcapsules(HC)fromsamples.Astereo-microscopewith25–40xmagnification was used for identifications. Head capsules weremountedas indicatedinMassaferroandBrooks(2002).Giventhepaucityofliteratureonchironomidsinthe lowland Neotropics, most specimens could be identified onlytogenuslevel.OstracodeandchironomidstratigraphicdiagramswereproducedusingGrapher7.ChironomidandostracodespecimensarestoredincollectionsoftheauthorsattheLaboratoriodeBiodiversidad,INIBIOMA,UniversidaddeComahue,Bariloche,Argentina,andIUG,TechnischeUniversitätBraunschweig,Germany.

FaunaldiversitywascalculatedinsamplesfromshortcoresusingtheShannonWienerIndex“H”(Krebs,1989).

ModernspatialdistributionofspeciesinLagoPeténItzáwaspresentedinPérezet al.(2010b),andshowedastrongrelationbetweenostracodespeciesassemblagesandwaterdepth. This relation justified the development of a transfer functiontoinferwaterdepthanditsapplicationtoassem-blagesintheshortcores.Allsamplesinthecalibrationdatasetwereincludedinthestatisticalanalysisbecauseostracodeswereabundant(>50valvesg-1)insediments.Forstatisticalanalysisandthesetupofourtransferfunction,weusedtheprogrampackagesPAST(Hammeret al.2001)andC2(Juggins,2003).Waterdataforcomparisonwiththe ostracode samples came from water profiles taken at thedeepestpointofthelake(17°00’N,89°51’W)(Pérezet al.,2010b).Sedimentconsistencywasrepresentedbythreeclasses drawn from sediment sample description in the field. Themoderntrainingsetincludessevenostracodespecies,awaterdepthrangefrom0.1to160m(median20m),and23surfacesedimentsamples.Abinomialcorrelation(BC)model(Wrozynaet al.,2009;Frenzelet al.,2010)wasusedforthereconstructionofwaterdepthinshortcoresoverthelast~525years.

RESULTS

Chronology

Core PI-SC-1-10mTotal210Pbactivitywas186Bqkg-1inthe0–2cm

section(Figure2).Maximumactivitywasfoundinthe2–4cmsection.Belowthat,sedimentsshowedaconsistentdeclinein210Pbactivitywithdepth.Minimumactivity(10Bqkg-1)wasreportedforthe36–38cmsection.Theactivityof214Pb,i.e.supported210Pbactivity,rangedfrom25to9.5Bqkg-1.Unsupported(excess)210Pbactivityateachlevelwascalculatedasthedifferencebetweentotal210Pband214Pbactivity,anddisplayedagenerallyexponentialdecaywithdepth.AccordingtotheCSRmodel,thetotalageofthesedimentcoreisabout525years,i.e.,thedateatthebaseis~1480AD.Thelong-term,meanlinearsedimentationrate is0.89mmyr-1.Agesolder than110yearswereestimatedroughlyusingthemeanmassaccumulationrateofthepast100years.Maximum137CsactivityinPI-SC-1-10m(21.6and20.5Bqkg-1)occurredat0.5and3cminthecore,correspondingto210Pbdatesof2003and1987,respectively.

PI-SC-2-40mTotal210Pbactivitydisplayedamaximumvalue(525

Bqkg-1)intheuppermost,0–2cmsectionanddeclinedwithdepth(Figure2).Theminimumactivity(36Bqkg-1)wasreportedatadepthof35cm.Theactivityof214PbwashigherthaninPI-SC-1-10mandrangedfrom41to23Bqkg-1.Unsupported210Pbrangedfrom484to13.5Bqkg-1.Theagemodelindicatedamaximumageat37.5cmof119years(1886)andthusahighermeanlinearsedimentation

Post-Columbian environmental history of Lago Petén Itzá, Guatemala 495

Total Pb [Bq kg ]210 -1

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Depth[cm]

PI-SC-2-40m PI-SC-1-10m

125

100

75

50

25

0

Massd

epth[kgm

]-2

CSR ages [years]

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Depth[cm]

214 -1Pb [Bq kg ]

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Depth[cm]

137 -1Cs [Bq kg ]

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Depth[cm]

Unsupported Pb [Bq kg ]210 -1

0 100 200 300 400 500 0 100 200 300 400 500 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 0 25 50 75 100

Figure2.AgemodelsofshortcoresPI-SC-1-10mandPI-SC-2-40m.

rate(4.3mmyr-1)thaninPI-SC-1-10m.Maximum137CsactivityinPI-SC-2-40mwas76.8Bqkg-1andwasmeasuredat1cmdepth,correspondingtoa210Pbdateof2004.Thereisdetectable137Csactivitybelowtheleveldatedto1954by210Pb(~20cmcoredepth),indicatingpossibletransferofsoluble137Cstodeepersediments,whichhasbeendocu-mented in other lake sediment profiles (Longmore et al.,1983;Hermanson,1990).

Sediment lithology

SedimentsthroughoutshortcorePI-SC-1-10marehomogenousandcharacterizedbylightolive-graysiltyclays.Twocoresectionspossesseddarkersediments,at0–8.5cmand22–24cmdepth(Figure3a).PI-SC-2-40mwascomposedofdarkolive-graysiltyclays.Theuppermost15cmofthecoreareslightlydarkerthanthebottomsedi-ments(Figure3b).Bothcoresweredominatedbyinorganicmatter(Figures3aand3b).Thehighestorganicmatter(OM)contentincoresPI-SC-1-10mandPI-SC-2-40mwasat3cmdepth(Figures3a,b).OMvariedgenerallyfrom7.3to 21.7 % of dry weight in PI-SC-1-10m (Figure 3a) and from 16 to 22.5 % in PI-SC-2-40m (Figure 3b). Short core PI-SC-1-10mdisplayedanincreaseinOMandadecreaseinthecarbonatecontentintheuppermost8.5cm,i.e.,since1944.ThehighestOMconcentrationinPI-SC-2-40m(17.8%) was detected at 27 cm depth. Carbonate content was higher in PI-SC-1-10m (the highest at 31 cm depth, 35.8 %)thaninPI-SC-2-40m(Figure3a).Thelowestcarbonatecontent (26.3 %) in PI-SC-1-10m was found at 1 cm depth (Figure 3a), and in PI-SC-2-40m (10.4 %) at 7 cm depth

(Figure3b).RapidhumansettlementofPeténbeginning~1960,correlateswellwiththetimingofhigherOMandlowercarbonatecontentinbothshortcores.XRDresults(notshown)indicatedthatcorePI-SC-1-10mwascomposedmainlyofcalcite.Montmorillonite,calcite,dolomiteandquartzweredetectedincorePI-SC-2-40m.

Sediment geochemistry

C/N ratio Sincetheearly1930s, totalcarbonandnitrogen

concentrationsinLagoPeténItzásedimentshavebeenincreasing,andtheorganiccarbon/totalnitrogen(C/N)ratiohasdecreased,atrendthatisclearsincearound1960(Figure4a).TotalC(organicandinorganic)rangedinPI-SC-1-10 m from 12.1 to 16.7 %, and in PI-SC-2-40 m from 9.4 to 10.4 %. Nitrogen (N) content was low in both cores. Total N in PI-SC-1-10m ranged from 0.2 to 1.0 %, and in PI-SC-2-40m from 0.4 to 0.7 %. Sections II, III, IV, and V (Figure4a)havelowernitrogenconcentrationsandhigherC/Nratio.Nitrogenconcentrationsincreasedat11,23,andat37cmdepthinshortcorePI-SC-2-40(Figure4b).C/NratiovariedthroughoutPI-SC-1-10mfrom13.0(1cmdeep)to48.2(33cmdeep).PI-SC-2-40mhadanarrowerrange of C/N ratio, which fluctuated from 12.0 to 20.3. The highest C/N ratios of this core were identified at 23 and 39 cm(sectionsIIIandV,Figure4b).

Major and trace elementsPI-SC-1-10m. Iron (Fe) concentration varied from

0.50 to 0.58 % (Figure 5a). Maximum values were found

Pérez et al.496

lowerlimitofdetection(LLD).PI-SC-2-40m. SectionsIandIIIinFigure5bdisplay

thehighestvaluesofFethroughoutthecore.Concentrationsvaried from 1.75 to 2.3 %. Br varied from 16.8 to 36.8 ppm and the profile displayed an increase from a depth of 10 cm to the top. The Sr profile exhibited high concentrations in sectionsIIandIII.Inbothcores,Srwastheelementthatpresented the highest concentrations, and in this core itranged from262 to368ppm.Thehighestconcentrationof Cu (54.6 ppm) was found at 37 cm, and the lowest(26.5ppm)valueat27cm(Figure5b).ZnandRbhavecomparable profiles, and their concentrations show a slight increaseatabout1880AD.Ingeneral,concentrationswerehighin theupper10cm,exceptfora lowZnvalueat3cm.Znvariedfrom36.4to63.6ppm,andRbfrom22.2to30.4 ppm. The Y profile fluctuated from 11.7 to 15.8 ppm throughouttheshortcore.Zrvariedfrom113to138ppm,andPbfrom15.2 to22.8ppm.Bothelementsdisplayedlowestconcentrationsat1cm.ThemaximumconcentrationofZrwasreachedat37cmandthemaximumconcentrationofPbat17cm.

atadepthof23to25cm(sectionIII).SectionsIIandIVdisplaythelowestvalues.Strontium(Sr)rangesfrom554to670ppm.Srconcentrationsstartedtodecreaseat11cm,i.e.,sincetheearly20thcentury.Therehasbeenanincreaseinbromine(Br)sincethe1950s,from10.5to27.5ppm.Thehighestconcentrationsweredetectedintheuppermost5 cm, since the mid 1970s. The copper (Cu) profile had highest concentrations at 1 cm (22.8 %, section I, Figure 5a),andfrom11 cm to 29 cm (max. conc. 24.2 %, sections II-IV). The zinc (Zn) profile displayed substantial variation, ranging from 1.4 to 20.1 ppm. Peaks in Zn concentration were identified at1cm,at7cm(sectionI),at19cm(sectionII),at27cm(sectionIII),andat33cmdepth(sectionIV).Rubidium(Rb) ranges from 7.8 to 12.0 ppm. The Rb profile displays aslightincreaseforthelast~190years,i.e.,theuppermost17cm.ThehighestconcentrationofRbwaspresentat1cm(12.0ppm).Yttrium(Y)rangedfrom0.1to1.7ppm.Themaximumvalueoccurredatasedimentdepthof25cm(1.7 ppm). Another peak was identified at 35 cm (1.0 ppm). Zirconium(Zr)andlead(Pb)concentrationswerebelowthe

Figure3.Organicmatterandcarbonatecontentinshortcoresa)PI-SC-1-10mandb)PI-SC-2-40m.Boldblacksquaresshowsectionsofdarkersedimentsgenerallydepositedsincethe1970s.

Post-Columbian environmental history of Lago Petén Itzá, Guatemala 497

I

II

b)

PI-SC-1-10m PI-SC-2-40m

I

II

III

IV

V

III

IV

Age [Years AD]

2005

1975

1930

1845

2005

Age [Years AD]

V

1900

1780

1480

1980

1954

1945

1885

1955

1680

12 13 14 15 16 17C (%)

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Dep

th (c

m)

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 1.2N [%]

10 20 30 40 50C/N (mass)

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

09 9.5 10 10.5 11

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8N [%]

12 14 16 18 20 22

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0a)

Dep

th (c

m)

C (%) C/N (mass)

Bioindicators: Ostracode and chironomid species assemblages

OstracodesSevenostracodespecieswere identified incore

PI-SC-1-10m(Figure6a),andsixincorePI-SC-2-40m(Table2,Figure6b).TheostracodefaunaconsistsofsomespeciesendemictothePeténLakeDistrictandtheYucatánPeninsulaandcloselyresembles themodernspeciesassemblagesfromLagoPeténItzá.Physocypria globula isanektonicspecies,Cypridopsis okeechobei,andStrandesia intrepidaarenektobenthicspeciesandCytheridella ilosvayi,Darwinula stevensoni,Limnocythere opesta,andPseudocandona sp.arebenthicspecies(Pérezet al.,2010a,inpress).Deep-water-corePI-SC-2-40mwasnotasostracode-richasshallow-water-corePI-SC-1-10m,wherespeciesabundancesanddiversitieswerehigher.

PI-SC-1-10m. ThedominantspeciesofthecorewasC. okeechobei, with a relative abundance of 23 to 54 %, and L. opesta (11–39 %). Cytheridella ilosvayi (7-37%), P. globula (2–13 %), D. stevensoni (1–8 %) and Pseudocandona sp.(1–15 %) were also abundant. Strandesia intrepidawastheleast abundant species (<1%), and was found only in the uppercentimetersofthecore.Diversitywashigher(H=1.62)intheshallow-watercorethaninthedeep-watercore,PI-SC-2-40m (H=0.22).Ostracodediversity andabundance

fluctuated throughout the core. Sections I and III (Figure 6a)displaypeaksofhighostracodediversity.Thehighestvalueswerereachedat1and5cm,i.e.,duringthelast~30years. The profile shows an increase in diversity in the upper 10 cm. A period with low abundances was identified from 13to19cm,i.e.,~1780–1880AD.Thelowestquantityofvalveswasreportedat3cm(814valvesg-1,sectionI,Figure6a)and31cm(298valvesg-1,sectionIII,Figure6a).

PI-SC-2-40m. PI-SC-2-40mwasdominatedprimarilybyP. globula,whichwas theonly speciespresent inallsedimentsamples(sectionsI-III,Figure6b).Thisspecieshas a relative abundance from 95 to 100 % throughout the core.P. globulaprefersawaterdepthof<40m(Pérezet al.,2010b).Abundanceofthisspecieshasincreasedsincetheearly1990s(9cmdepth),exceptinthelate1990swhenabundancedecreasedto228valvesg-1.VeryhighabundanceofP. globulaisaccompaniedbylowabundanceoftheotherostracodespecies,forinstanceat3and7cm.Cypridopsis okeechobei,L. opesta,D. stevensoni,andPseudocandona sp. were less abundant. Cytheridella ilosvayi was foundonlyintheuppermostcentimeters(sectionI,Figure6b).Ingeneral,diversityinthecorewaslow.Depthswithhigherdiversity were identified at 5 cm, from 13 to 17 cm, from 21to23cm,at31andat37cm.Thetotalnumberofvalvesvariedfrom79to856valvesg-1.

Figure4.TotalcarbonandnitrogenconcentrationsandorganicC/totalNratioofshortcores(a)PI-SC-1-10mand(b)PI-SC-2-40m.Graybarsindicatethedifferentsectionsusedforinterpretation.LowC/Nratiossuggestgreaterrelativecontributionfromphytoplanktonandthuseutrophication.

Pérez et al.498

I

II

III

IV

I

III

II

0.48 0.52 0.56 0.6Fe (%)

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Depth(cm)

8 16 24 32Cu (ppm)

0 6 12 18 24Zn (ppm)

0 10 20 30Br (ppm)

4 8 12 16Rb (ppm)

480 560 640 720Sr (ppm)

0 0.6 1.2 1.8Y (ppm)

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

1.6 1.8 2 2.2 2.4Fe (%)

50

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Depth(cm)

20 30 40 50 60Cu (ppm)

30 40 50 60 70Zn (ppm)

16 24 32 40Br (ppm)

20 24 28 32Rb (ppm)

240 300 360 420Sr (ppm)

10 12 14 16Y (ppm)

110 120 130 140Zr (ppm)

12 16 20 24Pb (ppm)

50454035302520151050

2005 AD19751930

1480

a)

1680

1880

2005 AD

19851970

b)

1890

ChironomidsChironomidsinbothshortcoreshadhigherspe-

ciesrichnessthanostracodes(Tables2and3).Table3presentsallchironomidtaxafoundinbothshortcores.Figure7displaysonlythemostdominantspecies.TotalabundancesweremuchlowerinPI-SC-1-10m(totalcounts≤10) than in PI-SC-2-40m (total counts ≤113). Since the minimumreliablenumberofHCpersampleis50,weareonlygivingageneraldescriptionofdiversitycompositionforthePI-SC-1-10m.Fivezones(sectionsI-V,Figure7)weredistinguishedinbothshortcores.Chironomidsweredescribedasmorphotypesbecausethelownumberoftaxonomic characteristics present in the HC is insufficient tomakedeterminationstospecieslevel.Inseveralcases,anumberorletterwasdesignatedalongwiththegenustoidentifydifferentmorphospecies(e.g.Tanytarsus1A,Cladotanytarsussp.2).

PI-SC-1-10mwasdominatedbyAblabesmiya sp.(≤100 %), Stempellinasp.andChironomus sp. (≤80 %), followedbyCryptochironomus sp.,TanytarsusD,orthocla-diinaeindet.,andParakiefferiella sp. (≤40 %, Figure 7a). Tanytarsus 1A was the least abundant species (≤16 %). From thebottomtoca.25cm(sectionV),aperiodofastableabundance was identified. The dominant taxa in section V andIIIwereAblabesmiyasp.,Stempellinasp.,Chironomussp.andCryptochironomussp.Nochironomidswerefoundat23,19,and7cm(sectionsIV,IIIandII).Chironomidsshowedagradualincreaseinabundanceanddiversityfrom

19to9cm(SectionIII),whereabundancedroppedsharply.Highestabundanceofchironomidswasfoundat5cm(13individuals,sectionI,Figure7a),at9cm(7individuals,sectionIII),andat21cm(6individuals,sectionIII).Theuppermost5cmofthecoreshowedaspeciesabundancedecrease.TheabundanceofChironomussp.,andTanytarsusDshowedaslightincreaseintheuppermost5cm,i.e.,sincethe late 1970s. The profile presents other peaks with higher abundancesat9,13,21,27,31,and33cm.

PI-SC-2-40m(Figure7b)possesses37chironomidspecies.Literatureregardingchironomidtaxonomyinthestudyareaisstillscantandthussomespecimenscouldnotbeidentified to species level. Only the most abundant species wereincludedinFigure7b.TheshortcorewasdominantedbyTanytarsus 1A (≤67 %), Cladotanytarsus sp.1andCladotanytarsus sp.2,Stempellinasp., Polypedilumsp.,andCoelotanypus/Clinotanypus. Less dominant species (≤20 %) were TanytarsusD,Labrundinia sp.,Cryptochironomussp., Paratanytarsus sp., Ablabesmiya sp.and, Cladopelma sp.Theremainingspeciesinthecoredisplayedrelativeabundances <10%.

Fromthebottomtoca.31cm(sectionV),theas-semblage was dominated (>20 %) by Tanytarsus1A,Cladotanytarsus sp. 1, Cladotanytarsus sp. 2, andStempellinasp.SectionsIVandIIIweremainlydomi-natedbyTanytarsus1A,andStempellinasp.Highestoverallabundancewasfoundatacoredepthof11cm(113individuals,sectionII,Figure7b).SectionIIshowed

Figure5.Elementconcentrationsinshortcore(a)PI-SC-1-10mand(b)PI-SC-2-40m.Graybarsindicatethedifferentsectionsusedforinterpretation.Lowconcentrations of Fe and high concentrations of Br indicate an increase in eutrophication. High Cu and Zn reflect an increase in anthropogenic impact. Pb isanindicatorofpollution.HigherRbandZn,andlowerSrconcentrationssuggesthighlakelevels.Yisindicativeofdistantaeoliansupply.

Post-Columbian environmental history of Lago Petén Itzá, Guatemala 499

0

a)

b)

I

II

III

I

II

IIIN NB B B B B

Cypridopsisokeechobei

40

30

20

10

0

Dep

th(c

m)

Cytheridellailosvayi

Limnocythereopesta

Darwinulastevensoni

Pseudo-candona sp.

Strandesiaintrepida

Physocypriaglobula

Totalvalves g-1

Diversity(H)

40

30

20

10

0

40

30

20

10

0

Dep

th(c

m)

40

30

20

10

00 400 800

0 1000 2000 0 800 1600 0 200 400 600 200 400 600 0 200 400 0 100 200 300 0 5 10 15 20 25 0 2000 4000 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.8

0 4 8 12 0 4 8 12 0 2 4 6 0 2 4 6 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0 400 800 0 0.1 0.2 0.3

Physocypriaglobula

Cypridopsisokeechobei

Limnocythereopesta

Darwinulastevensoni

Pseudo-candona sp.

Cytheridellailosvayi

Totalvalves g-1

Diversity(H)

NB B B N B B NB

2005 AD1987197519151880

1780

15801520

2005 AD19971990

1880

Figure6.Ostracodespeciesassemblages,totalnumberofvalvespergramofdrysediment,anddiversityinshortcore(a)PI-SC-1-10mand(b)PI-SC-2-40m.N:nektonic,NB:nektobenthic,B:benthic.

adecreaseintheabundanceofStempellinasp,andanincreaseofCladotanytarsussp.1,andParatanytarsussp.Atacoredepthof3cm,nochironomidswerefound(sec-tionI).Theupper2cmweredominatedbyTanytarsus1A,Coelotanypussp./Clinotanypussp.,andCladotanytarsussp.2.Thecoreshowedarelativelystableabundanceofchironomids,exceptforseveraldepthswithlowconcentra-tions,i.e.,23,31,and41cm.PeaksofChironomussp.wereidentified at 7, 15-17 and 33 cm.

Water depth transfer function

Todevelopanostracode-basedtransferfunction,weselectedsurfacesampleswithaminimumof100ostra-codespecimensandusedostracodespeciesdominance,ostracodediversityandtotalabundance,aswellaswaterdepth,organicmatterandCaconcentrationofthesediment,sedimentconsistency,andtheabundanceofgastropodsforCanonicalCorrespondenceAnalysis(CCA)(Mülleret al.,2009;Pérezet al.,2010).BecauseO2concentrationinthewaterhasaveryhighnegativecorrelationwithwaterdepth(Spearman’sr=-0.99)wedecidedtosubstitutewaterdepth

forO2concentrationintheanalysis.Watertemperatureandchemicaldata(conductivity,pH,ionconcentrations)wereexcludedfromanalysisbecauseoftheirverynarrowrangealongthedepthgradient(25.6–27.6°C;529–544µS/cm;pH8.1–8.5;seePerezet al.,2010b).Weassumedtheyarenotimportantindeterminingostracodedistribution.Twoostracodespecieswereexcludedbecausetheyoccurinless

Family CandonidaePseudocandonasp.Physocypria globula

Family CyprididaeCypridopsis okeechobeiStrandesia intrepida

Family DarwinulidaeDarwinula stevensoni

Family LimnocytheridaeCytheridella ilosvayiLimnocythere opesta

Table 2. List of ostracode species identified in both short cores.

Pérez et al.500

thanthreesamples(Cyprettasp.,Heterocypris punctata).TheCCAshowsthatwaterdepth(O2concentration)isthemain factor with a high loading on the first axis, and is significantly linked to organic matter (LOI 550 °C) and the abundanceofgastropods.Thesecondaxisislinkedmainlytosedimentconsistency(Table4).

Threeostracode-basedwater-depthtransferfunctionsweredevelopedusingourtrainingsetofrecentostracodedata:(1)abinomialcorrelation(BC)usingtheprogramEXCEL(cf.Wrozynaet al.,2009andFrenzelet al.,2010),(2)weightedaveraging(WA)withtolerancedownweighting

usingC2(cf.Juggins2003),and(3)amodernanalogue(MA)techniqueusingweightedthree-pointcorrelationofsamples.BecausetheperformanceoftheBCtransferfunctionwasthebestandonlyreliableone(Table5),weusedthismodelforlaterreconstruction.Below,wepresentthebinomialequationsthatwereusedtorelatewaterdepthtorelativeabundanceforalltaxathatdisplayedhighcorrelation(r)with water depth and contributed significantly to the transfer function(x = water depth in m). The correlation coefficient (r)ofthemodelwasvalidatedby“leaveoneout”crossvalidation(bootstrapping)(Figure8).Physocypria globula (%) = -0.002 x2+0.696x+5.517;

r =0.397Cypridopsis okeechobei (%) = 0.006 x2-0.964x+42.94;

r =0.276Cytheridella ilosvayi (%) = -0.003 x2+0.353x+12.55;

r =0.183Strandesia intrepida (%) = -0.039 x+1.731;

r =0.172

Water depth reconstruction

WeappliedthetransferfunctiontocorePI-SC-1-10m(Figure9).WedidnotapplyittocorePI-SC-2-40mbe-causea“non-modernanaloguesituation”provideduswithunrealisticwaterdepthresults.Thisanomalousresultwasreproducedbyallthreemodels.Thereconstructedwaterdepthduringthelast500yearsisshowninFigure9.Higherlake levels than today were identified in the late 1580s and 1640s.Alowerstagecharacterizedthetimefromaboutthemid-1700stotheearly20thcentury.Onceagain,higherlakelevelsareindicatedfortheperiodfromthelate1930stotheearly1990s,withtheexceptionoftheearly1970swhenlakelevelwaslow(MARN-AMPI,2008).

DISCUSSION

Recent eutrophication (1930s-2005 AD)

GeochemicaldataandbioindicatoranalysesofshortcoresPI-SC-1-10mandPI-SC-2-40mrevealedthatmodernculturaleutrophicationinLagoPeténItzástartedinthe20thcentury. Our results confirm the nutrient enrichment in the lakesince~1930AD,reportedbyRosenmeieret al.(2004).Thepreviousstudyusedgeochemicaldataanddiatomsinasedimentcoreasindicatorsforeutrophication,andcomple-mentsourstudybasedonostracodes,chironomids,andothergeochemicalvariables.

Loss-on-ignitionvaluesinbothshortcoresrevealedaslowincreaseinorganicmatterconcentrationandadecreaseincarbonatecontentsincethelate1930s,whensedimentsbecameslightlydarker.Totalcarbonandnitrogenhavealsoincreased since the late 1930s, confirming LOI results. High inputoforganicmatterduringthelastcenturymayexplain

Subfamily ChironominaeTribe Tanytarsini

Tanytarsus1ATanytarsus1CTanytarsusBTanytarsusCTanytarsusDTanytarsiniind.Micropsectrasp.Cladotanytarsussp.1Cladotanytarsussp.2Paratanytarsussp.Lauternboniellasp.

Tribe ChironominiChironomussp.Goeldochironomussp.Einfeldiasp.Endotribelossp.Apedilumsp.Cryptochironomussp.Paracladopelmasp.Cladopelmasp.Nilothauma/PegastiellaDicrotendipessp.Stempellinasp.Polypedilumsp.Pseudochironomussp.Chironominiindet.

Subfamily OrthocladiinaeParakiefferiellasp.Georthocladiussp.Corynoneurasp.Cricotopussp.Orthocladiinaeindet.

Subfamily TanypodinaeLabrundiniasp.Macropelopiasp.Procladiussp.Ablabesmiyasp.Alotanypussp.Coelotanypus/ClinotanypusFittkauimyasp.

Table 3. List of chironomid species identified in both short cores.

Post-Columbian environmental history of Lago Petén Itzá, Guatemala 501

a)

Tanyt

arsus

1A

Parakie

fferie

llasp.

Tanytars

usD

Cryptoc

hirono

mussp.

Chirono

mussp.

Stempel

linasp.

Orthocl

adiina

eindet.

Totalco

unts 4035302520151050

Ablabes

miyasp.

4035302520151050

Depth(cm)

I II

III

IV V

020

600

4080

040

800

2040

020

400

2040

020

400

816

04

8

2005

AD

1975

1955

1930

1780

1750

1715

1520

b)

Total co

unts

403020100

Cladota

nytars

ussp.

1

Tanytars

usD

Tanyta

rsusC

Tanytars

iniind

.

Tanytar

susB

Tanyta

rsus1C

Tanyta

rsus1A

403020100

Depth(cm)

Cladota

nytars

ussp.

2

Paratan

ytarsu

ssp.

Chirono

mussp.

Einfeldia

sp.

Cryptoc

hiron

omus

sp.

Paracla

dopel

masp.

Cladope

lmasp.

Stempel

linasp. Poly

pedilum

sp.

Pseudo

chiron

omus

sp.

Labrund

iniasp.

Proclad

iussp.

I

IV VIIIII

Coelot

anyp

ussp

./

Clinota

nypu

ssp.

Ablabe

smiya

sp.

040

80

020

40

030

030

030

030

010

20

010

20

010

20

010

20

010

20

010

20

05

10

05

10

03

6

03

602

4

03

602

4 01

230

12

3 060

120

2005

AD

2000

1980

1950

1910

1880

810

26

100

Figu

re7

.Chi

rono

mid

spec

iesa

ssem

blag

esa

ndto

talc

ount

sin

shor

tcor

e(a

)PI-

SC-1

-10m

and

(b)P

I-SC

-2-4

0m.

Pérez et al.502

therelativedecreaseincarbonatecontent.C/Nratioswereusedtoidentifytheoriginoftheorganicmatter(terrestrialversusaquatic)inthelakesediments.LowestC/Nratiosweremeasuredintheuppermostcentimetersoftheshortcores,andsuggestagreaterrelativecontributionfromphy-toplankton.Ratios<10aretypicalofalgae(Meyers,1994;KaushalandBinford,1999;Vaalgamaa,2007),whereashighervaluesindicatesomecontributionfrommacrophytesorterrestrialplants.Theshallow-watercore(PI-SC-1-10m)displayedhigherC/Nratiosthanthedeep-watercore(PI-SC-2-40m).Thisiscausedbyahighercontributionfromterrestrialorganicmattertothesesedimentsclosertotheshoreline. Terrestrial flora is high in carbon-rich support tissueslikecelluloseandlignin,whichleadstorelativelyhigherC/N.PI-SC-2-40mhadahighermeansedimentationrate(4.3mmyr-1)thanPI-SC-1-10m(0.9mmyr-1),probablyindicatingfocusingofsedimenttothedeeper-watersite,nearthebaseofthemetalimnion.ThehighersedimentationrateatthePI-SC-2-40mcoresitemayalsobeaconsequenceofproximitytolocalvillagesandsomesedimentloadfromtheRíoIxlú.

Othergeochemicaldata(Fe,Br,Cu,andZnvalues)alsopointtoaperiodofanthropogenicimpactinthe20thcentury.Ironconcentrationwasgenerallylowinbothshort

cores (≤ 2.3 %). PI-SC-2-40m yielded lower concentrations sincethelate1980s.Ironisassociatedwiththeinorganicfractionofthesediment(Brenneret al.,1990),whichwaslikelydilutedasprimaryproductivityandorganicsedimen-tationaccelerated.

Furthermore,organicmattercanalter theredoxenvironmentfromoxidizingtoreducing,atwhichpointreducedionicspeciesofFearereleasedintosolution.The presence or high abundance of the chironomidChironomus sp.inshortcoreswasaccompaniedbylowerironconcentrations,suggestinganoxicenvironments.Chironomuspossesshaemoglobin,whichallowsthemtosurviveunderhypoxicconditions(Walker,1995).Thisshowsthatchironomidscanbeusedas indicatorsforchangesinredoxconditions.SectionsofshortcorePI-SC-1-10malsodisplayedlowerabundancesofchironomids,whichwebelievearerelatedtoallochthonousinputsofsediment.Bromineisgenerallyboundtoorganicmatter,andresultsofthisstudysuggestitcanbeusedasanindicatorofeutrophication.OtherstudieshaveshownthatBrcanbeusedasanindicatorofdiatomproduction(Kerfootet al.,1999).Copperandzincaretwoofthebestindicatorsforpollutionandurbandevelopment.Thedeep-watercore,whichwascollectedclosertovillages,hadthehighestvaluesofCuandZn.Zninaquaticenvironmentscomesmainlyfrom industrial effluents, municipal wastewaters, emission fromsmeltingoperationsandfossil fuelcombustion(Vaalgamaa,2007).Highestzincconcentrationsweremeasured in theuppermostcentimetersofbothshortcores, indicating an increase in anthropogenic influence in recentyears.Copperalsoshowsanincreasesincethelate1930sinshortcorePI-SC-1-10m.Copperconcentrationispositivelycorrelatedwithorganicmattercontent,becauselike bromine, Cu shows strong affinity to organic matter. LeadvaluesinshortcorePI-SC-2-40mwerelow(<23ppm).AccordingtotheGeoaccumulationindex(Igeo)(Müller,1979),theseconcentrationscorrespondtoclassordegree“0,”whichisindicativeofalakewithoutPbpollution.SurfacesedimentsfromLagoPeténItzácontain>30ppmPb(unpublisheddata),indicatingmoderatelevelsofpollution.FuelcombustionanddecompositionoforganicmattercouldincreasePbconcentrationinsediments.Monitoringheavymetalconcentrationsisimportantbecausetheyaretoxic,non-degradable and have serious ecological ramifications inaquaticecosystems(JumbeandNandini,2009).

Weusedchironomidstoinferchangesintrophicsta-

Parameter axis 1 axis 2 axis 3eigenvalue 0.028 0.021 0.014

Ostracoda valves/mL -0.082 -0.124 -0.049Cypridopsis okeechobei 6.672 5.850 3.477Cytheridella ilosvayi -4.999 5.732 3.743Darwinula stevensoni 5.733 10.967 -18.673Pseudocandonasp. 1.376 9.281 -8.724Limnocythere opesta -4.927 8.636 7.740Physocypria globula 7.599 -0.097 3.045Strandesia intrepida 2.583 14.340 -18.123diversity 2.874 6.717 -1.578

Samples PI-5mN 0.022 0.349 -0.297PI-5mS 0.161 0.015 0.046PI-15mN -0.102 -0.078 -0.026PI-15mS 0.055 -0.031 -0.022PI-30mN -0.470 0.854 0.673PI-30mS 0.365 1.055 -0.261PI-50mS -0.017 -0.117 -0.021PI-100mN 0.272 0.165 0.189PI-100mS 0.224 0.198 0.155PI-160m 1.334 0.317 0.578

Environ-mental variable

waterdepth 0.756 -0.003 0.569organicmatter(LOI550°C) 0.683 -0.073 0.150Ca -0.675 0.132 -0.129consistency 0.155 -0.655 0.006gastropods -0.598 0.292 0.347

Table4.CanonicalCorrespondenceAnalysisforostracodeandenviron-mental data. The first axis is best explained by water depth (highlighted). Thesecondaxisisnegativelycorrelatedtosedimentconsistency(high-lighted).Wecannotexplainthethirdaxis.

Transfer function

Standard error (m)

Correlation coefficient

Binomialcorrelation 14.9 0.895Weightedaveraging 29.8 0.279Modernanaloguetechnique 37.0 0.277

Table5.Performanceofwater-depthtransferfunctionsforLagoPeténItzá.

Post-Columbian environmental history of Lago Petén Itzá, Guatemala 503

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

-50

-40

-30

-20

-10

0

10

20b)In

ferre

d w

ater

dept

h (m

)

Resid

uals

(m)

0

a)

Measured water depth (m) Measured water depth (m)0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180

y = 0.8639x + 14.817r = 0.8952

tusbecausespeciesexhibitawiderangeofenvironmentaloptimaandtolerances.InLagoPeténItzá,oppositetowhatweexpected,thedeep-watershortcorehadhigherdiversityandabundanceofchironomidsthantheshallow-watercore,whichdisplayedlowerconcentrationsoforganiccarbon.Duetothelowabundanceofchironomidsinshallow-watercorePI-SC-2-10m,thechironomidinterpretationisbasedonPI-SC-2-40m.ThechironomidrecordofLagoPeténItzáshowsagradualincreaseofabundancefromthebaseofthecoreupto~10cmdepth(ca.1980AD.),whenabundancestartstodecreasegradually.Atca.30–31cm,i.e.,thelate1910s,apronounceddecreaseinchironomidabundanceanddiversityisrecorded.Atthattime,onlyafewtaxawerepresent(Polypedilum, Tanytarsus, Stempellina y Cladotanytarsus).Thisreductioninnumbersoftaxaandabundancecouldhavebeenrelatedtowaterlevelchanges.Althoughtheabundanceoscillatesalongthewholesedimentsequence,from20cm(early1960s)to5cm(late1990s),thepresenceofChironomus, Procladius, Einfeldia reflects moreproductiveconditions(BrodersenandQuinlan2006),i.e.,highertrophicstatusinthelake.Theoveralldecreaseofchironomidabundanceintheuppermost10cmcouldberelatedeithertohighlevelsofeutrophicationthatimpactthefaunanegatively,ortorapidinputofbulksedimentduetoerosionorwaterlevelchange.

Incontrast,ostracodeabundanceanddiversityshowanincreaseduringthelast~20years.Ostracodesseemtobecorrelatedwithhigherorganicmatterandnutrientavail-abilityinthelake.However,itisimportanttoknowtheupperandlowerlimitsoftheirtolerance(Külköylüoglu,2004).Therearefewstudies(Scharf,1993;Mezquitaet al.,1999) about the influence of eutrophication on ostracodes, andthusabouttheirpotentialaseutrophicationindicators.Theutilityofostracodesasindicatorsofeutrophicationmaybeconfoundedbyseveralfactors.Forinstance,highorganicmattercontentinsedimentscouldleadtolowpH

andpoorpreservationofostracodesoftandespeciallyhardparts.Darwinula stevensoni,Physocypria globulaandPseudocandonasp.,however,seemtotolerateeutrophi-cationandcouldbeindicativeofachangeinthetrophicconditionofLagoPetenItzá.

EutrophicationinLagoPeténItzáwasprobablytrig-geredbyrapidhumanimmigrationintoPeténthatbegan~1960.Oneconsequencewasarapidincreaseinagriculture,fisheries, tourism and deforestation. Before 1960, >85 % of Petén was covered with tropical forest, but by 1990, 40 % ofPeténwascompletelydeforested(PainterandDurham,1995).Humanpopulationgrowth,urbanization,deforesta-tion,changinglanduse,andotherhumanactivitiesthatincreasenutrientinputratestothelake,arealteringthetrophicstatusofLagoPeténItzá,whichnowisconsideredoligo-mesotrophic. This is reflected in the declining water clarityofthelakeandgreateralgaeabundanceinthelit-toralzone.Thehumanpopulationcontinuestoincreaseandeutrophicationisemergingasacriticalissue.OtherlakesinGuatemalahavealsoexperiencedprofoundanthropogenicimpact.LakeAmatitlánhasreceivedmassiveamountsofsewageandindustrialwastefromGuatemalaCityandistodayhypereutrophic.OncepristineLakeAtitlánrecentlyexperiencedlargecyanobacteriablooms.Bothlakesareimportanttouristdestinations,anddeclinesinwaterqualitythreatentonegativelyimpactthelocaleconomies.

Lake level history of the last 500 years

High lake levels (1550-1730 and 1940-2005 AD)Theostracode-basedlakelevelreconstructionrevealed

two periods characterized by fluctuating, high lake levels (maximumrelativelakelevelof5m):(1)about1550-1730sand(2)about1940-2005AD,withtheexceptionoftheearly1970swhenannualmeanprecipitation(~1260mmyr-1)and

Figure8.a:Correlationbetweenmeasuredandinferredwaterdepths;b:residualsofourostracode-basedwater-depthtransferfunction(BC).

Pérez et al.504

1500

1550

1600

1650

1700

1750

1800

1850

1900

1950

2000

Relative lake level (m)

Yea

rsA

D

wetdry

0 5 10 15 20

Little Ice Age

lakelevelwerelow(MARN-AMPI,2008).Ourreconstruc-tiondoesnotshowthislakelevellowering.Forostracodeanalysisinshortcores,weused2-cmwetsedimentslices,whichdoesnotprovidesufficientlyhighresolutiontocaptureshort-termevents(~2years),andratherindicatesgeneral,longer-termchanges.Becausethestandarderrorisaboutequaltotheamplitudeofrelativelakelevelchangesindicatedbyourreconstruction,wecannotestimateexactlythehistoricalrelativelakelevels.Highlakelevelperiods,however,areclear.Theseinferencesaresupportedbygeo-chemicalanalysesandchironomidspeciesassemblages.Furtherevidenceisprovidedbymaximumrelativelakelevelsof+5mdocumentedfor1938(MARN-AMPI,2008).KaushalandBinford(1999)reportedthatC/Ninsedimentsincreasesafterdeforestationandlandclearance.Weidenti-fied high C/N ratios, approaching 50, in both cores during theperiods~1780-1840,~1940s,andintheearly1980s.ThesehighC/Nvaluesareprobablyrelatedtoheavyrainsthat caused flooding in the area and transported terrestrial organicmatterintothelake.Nevertheless,lakelevelin1938wasclearlymuchhigher.

RatiosofelementsSr,Rb,andZrmayalsoprovideinformationaboutmaterialinputintothelakeduringpe-riodsofhighprecipitation,andthushighlakelevels.Thestrontium profile is negatively related to the profiles for rubidiumandzirconium.RbandZrareelementsoriginatingmainlyfromsilicates.Silicateweatheringinthecatchment,enhancedbyprecipitation,couldaccountforhighercon-centrationsofRbandZr,andthuslowerSrinsediments.Aslightincreaseinashcontentintheuppermostcentimetersof the short cores confirms this, and is correlated with a periodofhighprecipitation.Similarconditionsprevailedaround1938.AccordingtotheInstitutodeSismología,Vulcanología,MeteorologíaeHidrología(INSIVUMEH),1938wastheyearwiththehighestannualaverageprecipita-tionduringthe20thcentury,andlakelevelrose~5m.ShortcoresdisplayedpeaksinconcentrationofRbandZratthattime,whileSrdecreased.Friedmanet al.(2000)reportsimilarresultsinTurkey,whereRbwasusedasaproxyforwetenvironments.

ScientistsandlocalinhabitantsinPeténobservedthatlevelsofLagoPeténItzároseduringthelastfewdecades.AccordingtoRice(1997),therisebeganafter1976andwasrelatedtoincreasedannualrainfall.Unfortunately,thedramaticriseofthelate1970stoearly1990sisnotfullydocumentedbymeteorologicaldata.WaterlevelvariationsinLagoPeténItzá,however,appeartohaveshiftedincon-certwithstagechangesinotherPeténwaterbodiessuchasSacpuy,SanDiego,Perdida,NaranjoandLasCuaches,stronglysuggestingaregionalclimaticcauseforlake-levelvariations.Deeveyet al.(1980)andINSIVUMEH(1985)studiedtheeffectthatprecipitationhasonlakelevelchangesinLagoPeténItzáandotheraquaticenvironmentsinthePetén Lake District. Their findings indicate that water level ofLagoPeténItzárisesabouttwomonthsafteraperiodofhighprecipitation.Regionalsubsoilsaresaturated,ac-

countingfortherelationshipbetweenlakelevelsandpre-cipitation.Whenheavyrainsoccurinthearea,thereisnocapacitytoabsorbincomingwaterthatentersthesystem,leading to rapid runoff and flooding.

Stable lake levels (1750s-1900s AD)Ourlakelevelreconstructionshowsthattheperiod

fromthelate1750stotheearly1900swascharacterizedbylakelevelssimilartothoseoftoday,probablycausedbyarelativelydryandcoolclimate.RbandFeconcentrationswereslightlylowerandstrontiumvalueshigher,suggest-inglessprecipitationthanduringtheperiodswithhighlakelevels.Ironisanindicatoroferosionofland-derivedmaterials(Hauget al.,2001)andlowvaluesindicatedrierclimate.C/Nratiosgraduallydecreasedfrom~45to35indicatinglesstransportofterrestrialorganicmattertothelakeduringthisperiod.Interestingly,ostracodeabundanceanddiversitydisplayedasharpdecreaseinthisperiod,perhapstriggeredbylowertemperatures.Forinstance,theostracodesC. ilosvayi,andC. okeechobei,whichpreferwarmerwaters(Pérezet al.,2010b),displayedadecreaseintheirabundancesduringthisperiod.

Figure9.Ostracode-basedwater-depthreconstructionforshortcorePI-SC-1-10m.DashedsquareshowstheperiodoftheLittleIceAge.Graylineindicatesinferredrelativelakelevelsandtheblacklineshowsafive-point smoothed line.

Post-Columbian environmental history of Lago Petén Itzá, Guatemala 505

The late Little Ice Age (~1500-1850 AD)ShortcorePI-SC-1-10mcontainssedimentsthatwere

depositedduringthelateLittleIceAge(LIA;1500-1850AD).AdditionalsedimentcoresfromLagoPeténItzá(A.Müller,personalcommunication)andotherstudiesfromnearbyregions(Hauget al.,2001;Hodellet al.,2005)suggestthatclimateinthenorthernlowlandneotropicsofCentralAmericaduringtheLIAwasdry,probablycausedbyamoresoutherlypositionoftheIntertropicalConvergenceZone(ITCZ).OurstudysuggeststhattheendoftheLIA(1750s-1850)wasdry,andlakelevelwasconsistentlylow.Ostracodediversitywasslightlyhigherduringthisperiodduetothefactthatlittoralzonesgenerallypresenthigherdiversityandabundanceofostracodes.Incontrast,theearly1580sandaround1650wererelativelywetandthelakelevelwashigh.δ18OvaluesfromostracodevalvesinsedimentcoresfromnearbyLakeSalpetén(Rosenmeieret al.,2002)showaslightdecreaseduringtheseyears,thusindicatinghighlakelevelandmoistconditions.AstudyinLagoVerde,alongthecoastoftheGulfofMexico,Mexico(Lozano-Garcíaet al.,2007)concludedthatlakelevelroseduringthe17thcentury.Theauthorssuggestedthatlakelevelfluctuations in Lago Verde were a response to solar forcing. Bothlakes,LagoVerdeandPeténItzá,lieinrelativelymoistareas,withannualmeanprecipitationof2500mmyr-1and1665mmyr-1,respectively.Thewetperiodduringtheearly1580sand~1650seemtohavebeenrelatedtoanincreaseinwinterprecipitation,butreducedsummermoisturesupply.DrierareasinthenorthernYucatánPeninsuladisplayedverydry conditions during these periods, as reflected in enriched δ18OvaluesinostracodevalvesandgastropodsextractedfromsedimentsofAguadaX’caamalandPuntaLaguna(Hodellet al.,2005;2007).

Yttrium and iron profiles of short core PI-SC-1-10m displayedtheirhighestvaluesat25cm(~1680AD)whichcoincidedwithperiodsofhigherprecipitationandlakelevels.Yttriumconcentrationsindicateadistantaeoliansupplyandcanbeusedasaproxyforwind-borneinputs(Minyuket al.,2007).

CONCLUSIONS

SedimentsfromLagoPeténItzá,Guatemalacontaingeochemicalandbiologicalevidenceforrecenteutrophi-cationandlakelevelchangesoverthelast~500years.Anincrease in eutrophication since ~1930s was identified in shallow-anddeep-watersedimentcores.Eutrophicationduringthisperiodwascharacterizedby:(1)highercon-centrationsoforganicmatter,andBrvalues,(2)lowerC/Nratios,carbonatecontent,andFevalues,(3)higherostracodeabundanceanddiversity,and(4)presenceofthehigh-pro-ductivitychironomidtaxaChironomus,Procladius,andEinfeldiafrom1960-2000AD.IncreasedCuandZncon-centrations in uppermost deposits reflect a recent increase inanthropogenicimpact.ThelakelevelhistoryofLago

PeténItzáwasreconstructedusingchangesintherelativeabundanceofostracodespecies,andshiftsinRb,Zr,andSrconcentrationsinshortcorePI-SC-1-10m.Higherlakelevels,upto+5m,from~1550tothe1730sandfromthe1940sto2005ADdisplayedhigherRbandZrvalues,lowerSrvalues,andhigherrelativeabundanceofPhysocypria globula.Theperiodfrom~1750totheearly1900swasatimeoflowerandmorestablelakelevelswhenSrconcentra-tionswerehigher.ThelatterpartoftheLittleIceAgewascharacterizedmainlybyadrierandcoolerclimate,andlowlakelevels,withtheexceptionofthelate16thcentury,whichhadhigherlakelevelsthatcoincidedwithhigherstandsatLagoSalpetén,GuatemalaandLagoVerde,México.ThissuggestsanincreaseinwinterprecipitationandamoresoutherlypositionoftheITCZ.Ourmulti-proxysedimentcorestudyofpastlakelevelisinagreementwithhistoricalflood and meteorological data from the 20thcentury.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the Universidad del ValledeGuatemala(UVG)andConsejoNacionaldeÁreasProtegidas(CONAP)forsupportprovidedduringthefieldtrip and to the Asociación de Manejo de la Cuenca PeténItzá(AMPI),andInstitutoNacionaldeSismología,Vulcanología,MetereologíaeHidrología(INSIVUMEH),InstitutoNacionaldeEstadística(INE)thatkindlypro-videduswithvaluabledata.SpecialthankstoMargaritaPalmieri,MargaretDix,RobertoMoreno,andEleonordeTott;RaúlCalderónforhisassistancemakingthemaps.EvgeniaVinogradova,WolfgangRiss,MalteLorenzandJulia Lorenschat for their help during the field campaigns andlaboratorywork.YvonneHermannsandBenjaminGilfedder(TechnischeUniversitätBraunschweig)fortheirassistanceduringgeochemicaldatainterpretation.DavidHodell(UniversityofCambridge),thestaffofthelabora-toryofGeochronologie&IsotopenhydrologieSektion,Leibniz-InstitutfürAngewandteGeophysik(LIAG),twoanonymousreviewersfordetailedcomments,andtheDeutscheForschungsgemeinschaft(DFG),whichkindlyprovidedfunding(GrantSchw671/3).

REFERENCES

Anselmetti,F.S.,Ariztegui,D.,Hodell,D.A.,Hillesheim,M.B.,Brenner,M.,Gilli,A.,McKenzie, J.A.,Mueller,A.D., 2006,LateQuaternaryclimate-inducedlakelevelvariationsinLakePeténItzá,Guatemala,inferredfromseismicstratigraphicanalysis:Palaeogeography,Palaeoclimatology,Palaeoecology,230(1-2),52-69.

Brenner,M.,Leyden,B.,Binford,M.,1990,Recent sedimentaryhistoriesofshallowlakesintheGuatemalansavannas:JournalofPaleolimnology,4(3),239-252.

Brenner,M.,Rosenmeier,M.F.,Hodell,D.A.,Curtis, J.H.,2002,PaleolimnologyoftheMayaLowlands:Long-termperspectivesoninteractionsamongclimate,environment,andhumans:AncientMesoamerica,13(1),141-157.

Pérez et al.506

Brezonik,P.,Fox,J.,1974,ThelimnologyofselectedGuatemalanlakes:Hydrobiologia,45(4),467-487.

Brodersen,K.,Quinlan,R.,2006,Midgesaspalaeoindicatorsoflakeproductivity,eutrophicationandhypolimneticoxygen:QuaternaryScienceReviews,25(15-15),1995-2012.

Brooks,S.J.,Birks,H.J.B.,2004,ThedynamicsofChironomidae(Insecta:Diptera)assemblagesinresponsetoenvironmentalchangeduringthepast700yearsonSvalbard:JournalofPaleolimnology,31(4),483-498.

Cheburkin,A.K.,Frei,R.,Shotyk,W.,1997,Anenergy-dispersiveminiprobemultielementanalyzer(EMMA)fordirectanalysisoftraceelementsandchemicalagedatingofsinglemineralgrains:ChemicalGeology,135(1-2),75-87.

Coffman,W.P.,De laRosa,C.,Cummins,K.W.,Wilzbach,M.A.,1992,Speciesrichnessinsomeneotropical(CostaRica)andAfrotropical(WestAfrica)loticcommunitiesofChironomidae(Diptera):NetherlandsJournalofAquaticEcology,26(2-4),229-237.

Curtis,J.,Hodell,D.,Brenner,M.,1996,ClimatevariabilityontheYucatanPeninsula(Mexico)duringthepast3500years,andimplicationsforMayaculturalevolution:QuaternaryResearch,46,37-47.

Curtis,J.,Brenner,M.,Hodell,D.,Balser,R.,Islebe,G.,Hooghiemstra,H.,1998,Amulti-proxystudyofHoloceneenvironmentalchangeintheMayaLowlandsofPeten,Guatemala:JournalofPaleolimnology,19(2),139-159.

Deevey,E.S.,Brenner,M.,Flannery,M.S.,Yezdani,G.H.,1980,LakesYaxhaandSacnab,Peten,Guatemala:Limnologyandhydrology:ArchivfürHydrogiologieSupplement,57,419-460.

DeutschesInstitutfürNormung(DIN),1998,DIN/18121-1,Determinationofwatercontentofsoilbytheoven-dryingmethod:Berlin,DeutschesInstitutfürNormungE.V.,BeuthVerlag,4pp.

Dole-Olivier,M.J.,Galassi,D.M.P.,Marmonier,P.,Chatelliers,M.C.,2000,Thebiologyandecologyofloticmicrocrustaceans:FreshwaterBiology,44,63-91.

Escobar,R.,2008,LluvianocesaenPetén:Guatemala,PrensaLibre,p.1.

Forester,R.M.,Smith,A.J.,1994,LateglacialclimateestimatesforsouthernNevada,theostracodefossilrecord:HighLevelRadioactiveWasteManagement,1,2553-2561.

Frenzel,P.,Wrozyna,C.,Xie,M.,Zhu,L.,Schwalb,A.,2010,Palaeo-waterdepthestimationfora600-yearsrecordfromNamCo(Tibet)usinganostracod-basedtransferfunction:QuaternaryInternational,218(1-2),157-165.

Friedman,E.S.,Sato,Y.,Alatas,A.,Johnson,C.E.,Wilkinson,T.J.,Yener,K.A.,Lai,B.,Jennings,G.,Mini,S.M.,Alp,E.E.,2000,Anx-ray fluorescence study of lake sediments from ancient Turkey usingsynchrotronradiation:AdvancesinX-rayAnalysis,42,151-160.

Hammer,Ø.,Harper,D.A.T.,Ryan,P.D,2001,PAST:Palaeontologicalstatisticssoftwarepackageforeducationanddataanalysis:PalaeontologiaElectronica,4(1),p.9.

Haug,G.H.,Hughen,K.A.,Sigman,D.M.,Peterson,L.C.,Röhl,U.,2001,SouthwardmigrationoftheIntertropicalConvergenceZonethroughtheHolocene:Science,293,1304-1308.

Heinrichs,M.L.,Walker,I.R.,Mathewes,R.W.,Hebda,R.J.,1999,Holocenechironomid-inferredsalinityandpaleovegetationreconstructionfromKilpoolalake,BritishColumbia:GeógraphiephysiqueetQuaternaire,53(2),211-221.

Heiri,O.,Lotter,A.F.,Lemcke,G.,2001,Lossonignitionasamethodforestimatingorganicandcarbonatecontent insediments:reproducibility and comparability of results: Journal ofPaleolimnology,25(1),101-110.

Hermanson,M.H.,1990,210Pband137Cschronologyofsedimentsfromsmall,shallowArcticlakes:GeochimicaetCosmochimicaActa,54(5),1443-1451.

Hillesheim,M.,Hodell,D.,Leyden,B.,Brenner,M.,Curtis,J.,Anselmetti,F.,Ariztegui,D.,Buck,D.,Guilderson,T.,Rosenmeier,M.,Schnurrenberg,D.,2005,ClimatechangeinlowlandCentralAmericaduringthelatedeglacialandearlyHolocene:JournalofQuaternaryScience,20(4),363-376.

Hodell,D.A.,Curtis,J.H.,Brenner,M.,1995,PossibleroleofclimateinthecollapseofClassicMayacivilization:Nature,375,391-394.

Hodell,D.A.,Brenner,M.,Curtis,J.H.,Medina-González,R.,ChanCan,E.I.,Albornaz-Pat,A.,Guilderson,T.P.,2005,ClimatechangeontheYucatanPeninsuladuringtheLittleIceAge:QuaternaryResearch,63(2),109-121.

Hodell,D.A.,Brenner,M.,Curtis,J.H.,2007,ClimateandculturalhistoryoftheNortheasternYucatanPeninsula,QuintanaRoo,Mexico:ClimaticChange,83(1-2),215-240.

Hodell,D.A.,Anselmetti,F.S.,Ariztegui,D.,Brenner,M.,Curtis,J.H.,Gilli,A.,Grzesik,D.A.,Guilderson,T.J.,Müller,A.D.,Bush,M.B.,Correa-Metrio,A.,Escobar,J.,Kutterolf,S.,2008,An85-karecordofclimatechangeinlowlandCentralAmerica:QuaternaryScienceReviews,27(11-12),1152-1165.

Holmes,J.,1998,AlateQuaternaryostracodrecordfromWallywashGreatPond,aJamaicanmarllake:JournalofPaleolimnology,19(2),115-128.

InstitutodeSismología,Vulcanología,MeteorologíaeHidrología(INSIVUMEH),1985,ReconocimientoHidrogeológicodelaCuencadelLagoPeténItzá:Guatemala,INSIVUMEH,115pp.

InstitutoNacionaldeEstadística(INE),2002,XICensoNacionaldePoblaciónyVIdeHabitación:Guatemala,InstitutoNacionaldeEstadística.

Islebe,G.,Hooghiemstra,H.,Brenner,M.,Curtis,J.H.,Hodell,D.,1996,AHolocenevegetationhistoryfromlowlandGuatemala:TheHolocene,6(3),265-271.

Juggins,S.,2003,UserguideC2,softwareforecologicalandpalaeocologicaldataanalysisandvisualisation,userguideversion1.3:NewcastleuponTyne,UniversityofNewcastle,DepartmentofGeography,69pp.

Jumbe,A.S.,Nandini,N.,2009,Heavymetalsanalysisandsedimentqualityvaluesinurbanlakes:AmericanJournalofEnvironmentalSciences,5,678-687.

Kaushal,S.,Binford,M.W.,1999,RelationshipbetweenC:Nratiosoflakesediments,organicmattersources,andhistoricaldeforestationinLakePleasant,Massachusetts,USA:JournalofPaleolimnology,22(4),439-442.

Kerfoot,W.C.,Robbins,J.A.,Weider,L.J.,1999,Anewapproachto historical reconstruction: combining descriptive andexperimentalpaleolimnology:LimnologyandOceanography,44(5),1232-1247.

Krebs,C.J.,1989,EcologicalMethodology:NewYork,HarperandRowPublishers,620pp.

Külköylüoglu,O.,2004,Ontheusageofostracods(Crustacea)asbioindicatorspeciesindifferentaquatichabitatsintheBoluregion,Turkey:EcologicalIndicators,4(2),139-147.

Laissaoui,A.,Benmansour,M.,Ziad,N.,IbnMajah,M.,Abril,J.M.,Mulsow,S.,2008,AnthropogenicradionuclidesinthewatercolumnandasedimentcorefromtheAlboranSea:applicationtoradiometricdatingandreconstructionofhistoricalwatercolumnradionuclideconcentrations:JournalofPaleolimnology,40(3),823-833.

Leyden,B.,1987,ManandclimateintheMayaLowlands:QuaternaryResearch,28(3),407-414.

Leyden,B.,Brenner,M.,Dahlin,B.H.,1998,CulturalandclimatichistoryofCobá,alowlandMayacityinQuintanaRoo,Mexico:QuaternaryResearch,49(1),111-122.

Little,J.L.,Smol,J.P.,2000,Changesinfossilmidge(Chironomidae)assemblagesinresponsetoculturalactivities inashallow,polymicticlake:JournalofPaleolimnology,23(2),207-212.

Longmore, M.E., O’Leary, B.M., Rose, C.W., 1983, Caesium-137 profiles inthesedimentsofapartial-meromicticlakeonGreatSandyIsland(FraserIsland),Queensland,Australia:Hydrobiologia,103(1),21-27.

Lozano-García,M.S.,Caballero,M.,Ortega,B.,Rodríguez,A.,Sosa,S.,2007,TracingtheeffectsoftheLittleIceAgeinthetropicallowlandsofeasternMesoamerica:ProceedingsoftheNationalAcademyofSciencesoftheUnitedStatesofAmerica,104(41),16200-16203.

Massaferro,J.,Brooks,S.J.,2002,ResponseofchironomidstoLate

Post-Columbian environmental history of Lago Petén Itzá, Guatemala 507

Quaternaryenvironmentalchange in theTaitaoPeninsula,southernChile:JournalofQuaternaryScience,17(2),101-111.

Massaferro,J.,RibeiroGuevara,S.,Rizzo,A.,Arribére,M.,2004,Short-termenvironmentalchangesinLakeMorenito(41°S,71°W,Patagonia,Argentina)fromanalysisofsub-fossilchironomids:AquaticConservation,15(1),23-30.

Massaferro,J.,Brooks,S.J.,Haberle,S.G.,2005,Thedynamicsofchironomid assemblages and vegetation during the LateQuaternaryatLagunaFacil,ChonosArchipelago,southernChile:QuaternaryScienceReviews,24(23-24),2510-2522.

Meyers,P.A.,1994,Preservationofelementaland isotopicsourceidentification of sedimentary organic matter: Chemical Geology, 114(3-4),289-302.

Mezquita,F.,Hernández,R.,Rueda,J.,1999,EcologyanddistributionofostracodsinapollutedMediterraneanriver:Paleogeography,Paleoclimatology,Paleoecology,148(1),87-103.

MinisteriodeAmbienteyRecursosNaturales,AutoridadparaelManejoyDesarrolloSostenibledelacuencadelLagoPeténItzáGuatemala(MARN-AMPI),2008,LíneadeBaseTerritorialparalacuencadelLagoPeténItzá:Guatemala,MARN-AMPI,ProyectoGU-T1021,Informe,256pp.

Minyuk,P.S.,Brigham-Grette,J.,Melles,M.,Borkhodoev,V.Y.,Glushkova,O.Y.,2007, InorganicgeochemistryofEl’gygytgynLakesediments(northeasternRussia)asanindicatorofpaleoclimaticchangeforthelast250kyr:JournalofPaleolimnology,37(1),123-133.

Mischke,S.,Almogi-Labin,A.,Ortal,R.,Rosenfeld,A.,Schwab,M.J.,Boomer,I.,2010,QuantitativereconstructionoflakeconductivityintheQuaternaryoftheNearEast(Israel)usingostracods:JournalofPaleolimnology,43(4),667-688.

Mourguiart,P.,Carbonel,P.,1994,Aquantitativemethodofpalaeolake-levelreconstructionusingostracodassemblages:anexamplefromtheBolivianAltiplano:Hydrobiologia,288(3),183-193.

Müller,G., 1979,Schwermetalle indenSedimentendesRheins-Veränderungenseit1971:UmschauinWissenschaftundTechnik,79,778-783.

Müller,A.D.,Islebe,G.A.,Hillesheim,M.B.,Grzesik,D.A.,Anselmetti,F.S.,Ariztegui,D.,Brenner,M.,Curtis,J.H.,Hodell,D.A.,Venz,K.A.,2009,ClimatedryingandassociatedforestdeclineinthelowlandsofnorthernGuatemaladuringthelateHolocene:QuaternaryResearch,71(2),133-141.

Nazarova,L.B.,Pestryakova,L.A.,Ushnitskaya,L.A.,Hubberten,H.W.,2008,Chironomids(Diptera:Chironomidae)inlakesofcentralYakutiaandtheirindicativepotentialforpaleoclimaticresearch:ContemporaryProblemsofEcology,1(3),335-345.

Painter,M.,Durham,W.H.,1995,ThesocialcausesofenvironmentaldestructioninLatinAmerica:Michigan,TheUniversityofMichiganPress,274pp.

Pérez,L.,Lorenschat,J.,Brenner,M.,Scharf,B.,Schwalb,A.,2010a,Extantfreshwaterostracodes(Crustacea:Ostracoda)fromLagoPeténItzá,Guatemala:RevistadeBiologíaTropical,58(3),871-895.

Pérez,L.,Lorenschat,J.,Bugja,R.,Brenner,M.,Scharf,B.,Schwalb,A.,2010b,Distribution,diversityandecologyofmodernfreshwaterostracodes(Crustacea),andhydrochemicalcharacteristicsofLagoPeténItzá,Guatemala:JournalofLimnology,69(1),146-159.

Pérez,L.,Lorenschat,J.,Brenner,M.,Scharf,B.,Schwalb,A.,inpress,Non-marineostracodes(Crustacea)ofGuatemala,in Cano,E.(ed.),BiodiversidaddeGuatemala:Guatemala,UniversidaddelValledeGuatemala.

Rice,D.S.,1997,IngenieríaHidráulicaenelCentrodePetén,Guatemala,inLaporte,J.P.,Escobedo,H.(eds.),XSimposiodeInvestigacionesArqueológicasyEtnología,Guatemala,1996:Guatemala,MuseoNacionaldeArqueologíayEtnología,581-594.

Robbins,J.A.,1978,Geochemicalandgeophysicalapplicationsofradioactiveleadisotopes,inNriago,J.P.(ed.),Biochemistryofleadintheenvironment:Amsterdam,Elservier,285-393.

Rosenmeier,M.,Hodell,D.,Brenner,M.,Curtis,J.,2002,A4000-yearlacustrinerecordofenvironmentalchangeinthesouthernMayaLowlands,Petén,Guatemala:QuaternaryResearch,57(2),183-190.

Rosenmeier,M.,Brenner,M.,Kenney,W.F.,Whitmore,T.J.,Taylor,C.M.,2004,RecenteutrophicationinthesouthernbasinofLakePeténItzá,Guatemala:humanimpactonalargetropicallake:Hydrobiologia,511(1),161-172.

Scharf,B.,1993,Ostracoda(Crustacea)fromeutrophicandoligotrophicmaarlakesoftheEifel(Germany)inthelateandpostGlacial,inMcKenzie,K.G.,Jones,P.J.(eds.),OstracodaintheEarthandLife Sciences: Balkema, Rotterdam, Brookfield, 453-464,

Scharf,B.,1998,EutrophicationhistoryofLakeArendsee(Germany):Paleogeography,Palaeoclimatology,Palaeoecology,140(1),85-96.

Scharf,B.,Bittmann,F.,Boettger,T.,2005,Freshwaterostracods(Crustacea)fromtheLateglacialsiteatMiesenheim,Germany,andtemperaturereconstructionduringtheMeiendorfInterstadial:Palaeogeography,Palaeoclimatology,Palaeoecology,225(1-4),203-215.

Schwalb,A.,2003,Lacustrineostracodesasstableisotoperecordersoflate-glacialandHoloceneenvironmentaldynamicsandclimate:JournalofPaleolimnology,29(3),256-351.

Smith,A.,1993,Lacustrineostracodesashydrochemicalindicatorsinlakesofthenorth-centralUnitedStates:JournalofPaleolimnology,8(2),121-134.

Vaalgamaa,S.,2007,TheeffectsofhumaninduceddisturbancesonthesedimentgeochemistryofBalticSeaembaymentswithafocusoneutrophicationhistory:Finland,UniversityofHelsinki,Ph.D.thesis,45pp.

Verschuren,D.,Laird,K.R.,Cumming,B.F.,2000,RainfallanddroughtinequatorialeastAfricaduringthepast1,100years:Nature,403,410-141.

Vinogradova,E.M.,RissH.W.,2007,Chironomidsof theYucatánPeninsula:Chironomus,20,32-35.

Wahl,D.,Byrne,R.,Schreiner,T.,Hansen,R,2006,HolocenevegetationchangeinthenorthernPetenandits implicationsforMayaprehistory:QuaternaryResearch,65(3),380-389.

Walker,I.R.,1995,Chironomidsasindicatorsofpastenvironmentalchange,in Armitage,P.,Cranston,P.S.,Pinder,L.C.V.(eds.),TheChironomidae:London,Chapman&Hall,405-422.

Watson,C.N.,Heyn,M.W.,1992,ApreliminarysurveyoftheChironomidae(Diptera)ofCostaRica,withemphasisonloticfauna:NetherlandsJournalofAquaticEcology,26(2-4),257-262.

Wooller,M.J.,Francis,D.,Fogel,M.L.,Miller,G.H.,Walker,I.R.,Wolfe,A.P., 2004, Quantitative paleotemperature estimates from δ18OofchironomidheadcapsulespreservedinArcticlakesediments:JournalofPaleolimnology,31(3),267-274.

Wooller,M.J.,Morgan,R.,Fowell,S.,Behling,H.,Fogel,M.,2007,AmultiproxypeatrecordofHolocenemangrovepalaeoecologyfromTwinCays,Belize:TheHolocene,17(8),1129-1139.

Wrozyna,C.,Frenzel,P.,Schwalb,A.,Steeb,P.,Zhu,L.P.,2009,WaterdepthrelatedassemblagecompositionofrecentostracodainLakeNamCo,southernTibetanPlateau:RevistaEspañoladeMicropaleontología,41,20.

Manuscriptreceived:April6,2010Correctedmanuscriptreceived:July29,2010Manuscriptaccepted:August5,2010