Saving and Investment - San Francisco State...

Transcript of Saving and Investment - San Francisco State...

San Francisco State University Michael BarECON 302

Saving and InvestmentThe process of economic growth depends, among other things, on the ability of �rms to

expand their productive capacity through investment in additional equipment. Firms can�nance their investment from retained earnings (also called undistributed pro�ts or businesssaving) or borrow funds from households who save. In this chapter we discuss the relationshipbetween saving and investment in the macroeconomy, and present a theory of saving andinvestment. We will examine what factors a¤ect investment decisions by the �rms and savingdecisions by the households, and how those decisions are a¤ected by government policies.Before we start the formal discussion of saving and investment, we need to introduce two

general concepts. A stock variable is a magnitude measured at a point in time (say atthe end of the year), and a �ow variable is a variable measured over a given time interval(say over the year). For example, the stock of capital in the U.S. on December 31st 2014,is a stock variable. Investment that took place during 2014 is a �ow variable. As anotherexample, the saving during 2014 is a �ow variable and the savings at the end of 2104 (thevalue of all the balances of savings accounts) is a stock variable. Thus, the �ow variablesdetermine the value of the stock variables at the end of a period.

1 Saving and Investment Equation

In any economy there exists an accounting identity that relates saving and investment. Inthis section we derive this relationship, called the saving and investment equation. TheGDP is given by

GDP = C +G+ I +NX (1)

where C is personal consumption expenditure, G is government consumption expenditure,I is gross domestic investment, and NX = X � IM is net exports (exports minus imports).We de�ne disposable income as

Y D = GDP + TR� T (2)

where TR are transfer payments by the government (such as unemployment insurance ben-e�ts, social security, medicare,...), and T is taxes. We de�ne the private saving as

SP = Y D � C (3)

That is, the private saving is the disposable income that is not consumed. Similarly, thegovernment saving is

SG = T � TR�G (4)

which is the government income that is not spent on government consumption or transferpayments. Government de�cit is then

Def = �SG = G+ TR� T (5)

1

Now add TR and subtract T from equation (1)

GDP + TR� T = C +G+ TR� T + I +NX

Now using the de�nition of disposable income in equation (2) and government de�cit (5),gives

Y D = C +Def + I +NX

or

Y D � C| {z }Sp

�Def = I +NX

Finally, using the de�nition of government de�cit Def = �SG, gives the saving and in-vestment equation:1

S = SP + SG = I +NX (6)

The left hand side of (6) is the gross domestic saving S, which is the sum of private andgovernment saving. On the right hand side we have the gross domestic investment I and netexports NX, which is also known as Net Foreign Investment. In a closed economy wehave

SP + SG = I

that is, in a closed economy the total saving is equal to total investment. In an open economyhowever, it is possible that some of the domestic saving can fund investment abroad, if S > I.It is also possible in an open economy that the domestic saving is insu¢ cient to fund allof the domestic investment, if S < I, and in this case part of the domestic investment isfunded by foreigners. If NX > 0, then the economy is exporting more goods and servicesthan what it imports, i.e. the country is experiencing a trade surplus. This means that thedomestic economy is accumulating foreign assets, since the rest of the world has to borrowfrom the domestic economy. If on the other hand, NX < 0, this means that the economy isimporting more goods and services than its exports to the rest of the world, i.e. the countryis experiencing trade de�cit (trade de�cit is de�ned as �NX). In this case the domesticeconomy has to borrow from the rest of the world and the rest of the world is accumulatingdomestic assets. Thus, in the open economy, total saving is equal to the domestic investmentplus net foreign investment, as equation (6) statesWhat can we learn from the saving and investment equation (6)?

1. Let the focus be the gross domestic investment, and its funding. The domestic in-vestment can be �nanced by domestic saving and by foreign saving. Rewriting (6)gives

I = SP + SG �NX1For simplicity, we ignore income receipts from the rest of the world and income payments to the rest

of the world. If we had done that in the above steps (i.e. de�ned Y D = GDP + TR � T+ Net incomepayments from the rest of the world), the more correct saving and investment equation would have beenSP + SG = I + CA, where CA is the balance on current account. In these notes, we ignore the di¤erencebetween current account and trade account.

2

The term �NX represents the investment of the rest of the world in the domesticeconomy. For example, if I = 20, SP + SG = 15 and NX = �5, then

I|{z}20

= SP + SG| {z }15

�NX|{z}�5

which means that part of the domestic investment is �nanced by domestic saving (15)and part is �nanced by foreign saving (5).

If on the other hand we have I = 20, SP + SG = 25 and NX = 5, then

I|{z}20

= SP + SG| {z }25

�NX|{z}5

which means that the domestic saving �nances not only the domestic investment, butalso �nances some of the investment in the rest of the world.

2. Now, let the focus be the government de�cit. The government can �nance its de�citin two ways: (1) borrowing from domestic residents or (2) borrow from the rest of theworld. Rewriting equation (6) gives

SP + SG = I +NX

Def = SP � I �NX

Thus, we can see that an increase in government de�cit has to be associated with eitherincrease in private saving, or with a decrease in gross domestic investment or with anincrease in the trade de�cit (borrowing from abroad).

2 Saving and Investment in the U.S.

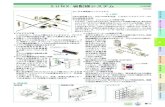

Lets take a look at the behavior of total gross domestic investment and gross saving inthe U.S. and how it was �nanced. Figure (1) shows the total gross domestic investmentand gross saving in the U.S., as a fraction of GDP, since 1929. Observe the huge fall ininvestment and saving during the great depression in early 30s. After World War II, theinvestment rate in the U.S. has �uctuated between 20% and 25% of GDP, for the mostpart, and it fell to 17.5% during the great recession. The saving rate, after World War II,has �uctuated between 15% and 25% for the most part, and fell to 14.9% during the greatrecession. Notice that up until the early 80s, the domestic saving was almost the same asinvestment, meaning that domestic saving was just enough to �nance the investment. Sinceearly 80s however, the domestic saving fell below the domestic investment, which means(recall that I = SP + SG �NX) that part of the domestic investment had to be funded byborrowing from foreigners.Let us have closer look into the components of saving, namely private and government

saving: S = SP + SG. Figure (2) shows the private saving as a fraction of GDP. The grossprivate saving, after World War II, has been �uctuating around 20%. You can detect anupward trend from the end of World War II until mid 80s, followed by a downward trendsince the mid 80s. Figure (3) shows the government saving as a fraction of GDP.

3

Figure 1: Domestic Investment and Saving (% of GDP).

Figure 2: Gross Private Saving (% of GDP).

Notice that in recent years the government is running a budget de�cit, and during thegreat recession the government de�cit approached 8% of GDP. This de�cit was almost as largeas the one attained during World War II. Thus, the government does not "help" to �nancethe domestic investment. Therefore, the rest of the funding for the domestic investment hasto come from abroad. Figure (4) shows the current account balance as a fraction of GDP.We can see that in the last 30 years the U.S. is experiencing current account de�cit.

This means that part of the U.S. domestic investment is funded by foreigners, and thatforeigners accumulate U.S. assets. For example, in 2006 the gross domestic investment (asa fraction of GDP) was I=GDP = 23:33%, and gross domestic saving (as a fraction ofGDP) was S=GDP = 17:53%. Thus, using the saving and investment equation (6), with all

4

Figure 3: Gross Government Saving (% of GDP).

Figure 4: Balance on Current Account (% of GDP).

magnitudes expressed as percentage of GDP, gives

I|{z}23:33%

= SP + SG| {z }17:53%

�NX|{z}?

The current account therefore must be �5:80%, which represents that part of domesticinvestment funded by foreigners.

5

3 Intertemporal Choice Model (Saving Theory).

In the �rst section of these notes we showed the relationship between saving and investmentin the economy, called the saving and investment equation:

S = I +NX

Our next goal is to investigate the determinants of saving and investment. In this section webuild a model in which consumers make explicit decisions about consumption and saving.Before presenting the model, let�s take a moment to think about what factors might a¤ectthe saving decision of households. We point out three factors that might be importantdeterminates of saving.Why do people save? Saving is a process of giving up current consumption in order

to increase the future consumption. Therefore, we expect that our saving decisions woulddepend on our current and future income. Typically, individuals who work and expect adecrease in their income when they retire, tend to save some of their current income forretirement. In contrast, other individuals who expect an increase in their future income,tend to borrow (have negative saving). For example, many students take student loans whilethey are studying, and plan to repay the loan when they graduate and earn higher income.Therefore, current and future income, are among the most important factors that a¤ect thesaving decisions.Another important factor that a¤ects the saving decision is the interest rate. If an

individual gives up some of his current consumption and decides to save, he will be able toincrease his future consumption. But the question is by how much? The real interest rategives the answer to that question. If you walk into a bank and open a savings account, theinterest rate that the bank will o¤er you is a nominal interest rate.

De�nition 1 The nominal interest rate is the extra dollars one gets in the future whenhe saves one dollar today.

For example, if the annual nominal interest is i = 10%, this means that when you deposit$1 today, you will receive your $1 back, plus $0:1 interest. Thus, the total return on every$1 saved is (1 + i) dollars, and the net return is i. What consumers care about though isnot how much money they got, but how much consumption they can buy with their money.Suppose that the price of consumption basket today is pt and next period pt+1. Giving upone unit of consumption today, frees up pt dollars. Saving this money at nominal interestrate i gives pt (1 + i) dollars next period, which can buy pt (1 + i) =pt+1 units of consumptionnext period.

De�nition 2 The real interest rate is the extra amount of consumption that one gets inthe future when he gives up one unit of consumption today.

Thus, the extra consumption in period t + 1, on top of the 1 unit given up at time t isthe real interest rate:

r =pt (1 + i)

pt+1� 1

6

Let � = pt+1pt� 1 be the in�ation rate between periods t and t + 1. Then the relationship

between the nominal interest rate and the real interest rate can be written as:

1 + r =1 + i

1 + �

If the nominal interest rate and the in�ation rates are small, then we can derive an approx-imation formula to the above. Taking ln (�) from both sides gives

ln (1 + i)� ln (1 + �) = ln (1 + r)

If i; r and � are small, the above is approximately

r � i� �

Thus, the real interest rate is approximately equal to the nominal interest rate minus thein�ation rate.

Example 3 Suppose that the nominal interest rate is i = 5%, and in�ation rate is 3:5%.The real interest rate is

r =1 + i

1 + �� 1 = 1 + 0:05

1 + 0:035� 1 = 1:45%

Or approximatelyr � i� � = 5%� 3:5% = 1:5%

To summarize this discussion, since real interest rate determines how much extra futureconsumption we expect to get when we save one unit of current consumption, then we suspectthat the real interest rate would be one of the pivotal factors that a¤ect our saving decisions.The third factor that determines saving is our preferences. An individual who values

current consumption a lot and does not value future consumption much (someone who �livesthe day�), will tend to save little or even borrow. On the other hand, someone who valuesfuture consumption or consumption of his children and grandchildren a lot will tend to savemore. The three factors that a¤ect the saving decision are therefore, preferences, currentand future income, and the real interest rate.

3.1 The Model

Consumers: There are N identical consumers that live for two periods (1 and 2) and deriveutility from consumption c1 and c2 in the two periods: U (c1; c2). Consumers receive incomey1 and y2 in the two periods and pay a lump sum tax t1 and t2 to the government. Theconsumers decide how much to consume in each period and how much to save in the �rstperiod. We denote the saving in the �rst period by s. Consumers can borrow and lend atreal interest rate r, which is assumed exogenously given. Thus the budget constraints in thetwo periods are:

[BC1] : c1 + s = y1 � t1[BC2] : c2 = y2 � t2 + (1 + r) s

7

The consumers�problem is therefore

maxc1;c2;s

U (c1; c2)

s:t:

[BC1] : c1 + s = y1 � t1[BC2] : c2 = y2 � t2 + (1 + r) s

Note that if s > 0, the consumer is saving (lending), while s < 0 means that the consumeris borrowing in the �rst period.Government: The government collects tax revenues T1 = N � t1 and T2 = N � t2 in the

two periods and spends G1 and G2 in the two periods. The government can borrow and lendat real interest rate r with the constraint that the present value of spending = present valueof taxes

G1 +G21 + r

= T1 +T21 + r

This means that if the government runs a de�cit in the �rst period, it must borrow theamount of the de�cit and pay that amount, plus interest, with the second period�s surplus.And if the government has a surplus, it can save the surplus at interest r and be able toa¤ord a de�cit in the second period. To see this, rearrange the above condition

(G1 � T1) (1 + r) = T2 �G2

Suppose that the real interest rate is r = 5% and in the �rst period the government runs ade�cit of 100, thus G1�T1 = 100. The above condition means that in the second period thegovernment must have a surplus of 105 to pay the debt, i.e. T2 �G2 = 105.Now that we have completed the description of the model we would like to analyze the

impact on consumers of the changes in the exogenous variables:

1. Changes in income: y1 and y2

2. Changes in the real interest rate: r

3. Changes in government taxes: T1 and T2

To answer the above questions we need to solve the consumers�problem. It is convenientto derive the lifetime budget constraint of the consumer. Substitute s from the second periodbudget constraint into the �rst period�s budget constraint. It is easy to do when you divideboth sides of BC2 by 1 + r to get

BC2 :c21 + r

=y21 + r

� t21 + r

+ s

Now add the two budget constraints and get the lifetime budget constraint:

c1 +c21 + r| {z }

PV of lifetime consumption

= y1 � t1 +y2 � t21 + r| {z }

we = PV of lifetime wealth

8

Thus, the left hand side is the present value of lifetime consumption, and the right hand sideis the present value of lifetime net of taxes income, which we call the lifetime wealth (we).The consumers�problem can then be rewritten as:

maxc1;c2

U (c1; c2)

s:t:

c1 +c21 + r

= y1 � t1 +y2 � t21 + r

Interpretation: Recall the consumer choice model of choosing the optimal amounts of twogoods x and y, with budget constraint pxx+pyy = I (from the micro foundations appendix).In that model the slope of the budget constraint (in absolute value) is px=py, which is therelative price of good x in terms of good y. Notice that the two period model is very similarto the general model of consumer choice, where the two goods are current consumption andfuture consumption (c1 and c2). We can write the budget constraint concisely as:

c1 +c21 + r

= we

which is similar to the budget constraint from micro foundations:

pxx+ pyy = I

The price of c1 is 1, and the price of c2 is 11+r, thus the slope of the budget constraint

is (1 + r), and it represents the relative price of current consumption in terms of futureconsumption. Indeed, consider the cost of increasing current consumption by 1 unit. If theconsumer saved that unit, then he would have enjoyed an increase of 1 + r units in thefuture consumption. Hence, the opportunity cost of current consumption in terms of futureconsumption is 1 + r. Thus the consumer can choose the optimal bundle of two goods (c1and c2), given his preferences and given the prices of the two goods. The next �gure showsthe graph of the lifetime budget constraint.

9

)1( rwe +

E22 ty −

1cwe

11 ty −

Slope = )1( r+−

2c

With free borrowing and lending, it is feasible for this consumer to consume all his wealthin the �rst period and nothing in the second: (c1 = we; c2 = 0). Similarly, it is feasible forthis consumer not to consume anything in the �rst period and consume all his wealth in thesecond period: (c1 = 0; c2 = we (1 + r)). Also notice that it is feasible for the consumerto consume in each period the income (net of taxes) received in that period: (c1 = y1 � t1;c2 = y2 � t2). This bundle is denoted by E is the consumer�s endowment. If the consumerwas not allowed to borrow or lend, then he would be forced to consume his endowment,i.e., his net of taxes income in each period. Because the consumers are free to borrow andlend at real interest rate r, they can chose other points on the budget constraint. If theconsumer chooses a point above E on the lifetime budget constraint, then he is a lender(his current consumption is less then current income, so he is saving a positive amount).If the consumer chooses a point below E on the lifetime budget constraint, then he is aborrower (his current consumption is greater than his current income, so he has negativesaving).

10

3.2 Optimal Choice

The next �gure shows the optimal choice for a consumer who is a lender.

A

)1( r+−s*>0

*2c

)1( rwe +

E22 ty −

1c

2c

we11 ty −*

1c

At the optimal bundle (point A) we have the usual condition that the marginal rate ofsubstitution between c1 and c2 is equal the relative price. That is

U1 (c1; c2)

U2 (c1; c2)= 1 + r

The left hand side is the (absolute value of) the slope of the indi¤erence curves and the righthand side is the (absolute value of) the slope of the budget constraint. This should look veryfamiliar to you and similar to the optimality condition

Ux (x; y)

Uy (x; y)=pxpy

11

Notice that in the case of a lender, the saving is positive. The next �gure shows the optimalchoice for a consumer who is a borrower.

E

)1( r+−s*<0

22 ty −

)1( rwe +

A*2c

1c

2c

we*1c11 ty −

Notice that the saving is negative for a borrower.

3.3 Changes in income

In this section we want to analyze the impact of changes in y1 and y2 on the consumer�schoice (c�1; c

�2; s

�). The consumer�s lifetime budget constraint is

c1 +c21 + r

= y1 � t1 +y2 � t21 + r

3.3.1 An increase in current income (y1 ")

We see from the budget constraint that an increase in y1 will shift the budget constraintto the right. If we assume both goods (current consumption and future consumption) arenormal, the consumer will increase the consumption in both periods. In order to increase theconsumption in the second period the consumer must increase his saving. Thus, an increasein the current income will increase the current consumption by less than the change in thecurrent income. We call this result consumption smoothing.To summarize:

y1 " ) c�1 "; c�2 "; s� "; �c1 < �y1

12

3.3.2 An increase in future income (y2 ")

We see from the budget constraint that an increase in y2 will shift the budget constraintto the right. Given that both goods (current consumption and future consumption) arenormal, the consumer will increase the consumption in both periods. In order to increasethe consumption in the �rst period the consumer must decrease his saving. Thus, an increasein the future income will increase the future consumption by less than the change in the futureincome.To summarize:

y2 " ) c�1 "; c�2 "; s� #; �c2 < �y2

3.3.3 An increase in current and future income (y1 "; y2 ").

The budget constraint will shift to the right and again consumption in both periods will goup. It is unclear however what will happen to the saving. The impact on saving depends onthe relative magnitudes of the changes in y1 and y2.To summarize:

y1 "; y2 " ) c�1 "; c�2 "; s�?

3.3.4 Temporary vs. Permanent changes in income

The main point of the above experiments was to show that if the increase in income happensonly in one period, then the consumer will increase his consumption in that period by lessthan the change in that period�s income. This is called consumption smoothing. Noticethat we derived this result without making restrictive assumptions about preferences (e.g.Cobb-Douglas), and we only assumed that c1 and c2 are both normal goods.Is there evidence in the data of consumption smoothing? The next �gure shows the

percentage deviation from trend of real consumption per capita and real GDP per capita inthe U.S. What we can see from the next �gure is that consumption is smoother than GDP.

Detrended GDP, Consumption

0.08

0.06

0.04

0.02

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

194

7I

195

3II

195

9III

196

5IV

197

2I

197

8II

198

4III

199

0IV

199

7I

200

3II

Time

% D

evia

tion

det_GDPdet_C

13

3.4 Changes in the real interest rate

Suppose that r ". What is the e¤ect of the increase in real interest rate on the lifetime budgetconstraint? First of all, the slope of the budget constraint will increase in absolute value(it will become more steep). Also notice that whatever the interest rate, since the incomesand taxes did not change, the new budget constraint has to pass through the endowmentpoint E. Regardless of the interest rate it is always feasible to consume in each period thatperiod�s income. The next graph shows the e¤ect of r " on the lifetime budget constraint.

A

B

11 ty −

2c

)1( rwe +

E22 ty −

1cwe

The dashed line is the new budget constraint, after r ".An increase in the real interest rate has two e¤ects on the consumer. On the one hand

the relative price of current consumption in terms of future consumption, (1 + r), has goneup. As a result, the consumer would like to substitute (the now more expensive) currentconsumption with the (the now cheaper) future consumption. This is called the substitutione¤ect �the change in consumption that results from the change in the relative prices. As aresult of the substitution e¤ect the consumer will reduce current consumption and increasefuture consumption. Thus, as a result of the substitution e¤ect we have: c�1 #; c�2 ".But there is another e¤ect. Notice that if the consumer was lender before the change (for

example chose the point A), then after the change he can still a¤ord the original bundle, andeven bundles that contain more of both goods than A. In other words, his purchasing powerincreased. We call this increase in purchasing power a positive income e¤ect. For a borrower(one who consumed at point B for example) the opposite happened. After the change hecan no longer a¤ord the previous bundle. We call this decrease in the purchasing power anegative income e¤ect.

14

Our de�nition of income e¤ect is not precise, but it is intuitive and su¢ cient for thepurpose at hand. So for us a positive income e¤ect occurs if at the new prices, even if youtake some of the consumer�s income he can still a¤ord the old bundle. We say that a negativeincome e¤ect occurs if at the new prices the old bundle is not a¤ordable.Assuming that both goods are normal implies that the positive income e¤ect will cause

for the lender c�1 "; c�2 " and for the borrower c�1 #; c�2 #. The next table summarizes theresults of r ":

Lender BorrowerSubstitution e¤ect c�1 #; c�2 " c�1 #; c�2 "Income e¤ect c�1 "; c�2 " c�1 #; c�2 #Total e¤ect c�1?; c

�2 " c�1 #; c�2?

After analyzing the e¤ect of r " on consumption, we can �gure out what will happen tosaving. The �rst period budget constraint is [BC1] : c1+s = y1�t1. Notice that r " does notchange the right hand side y1� t1. Thus, since for the borrower we found that c�1 #, we musthave s ", to keep BC1 from violating. At �rst look, it may seem that 2nd period consumptionmust increase, because in the term (1 + r) s, both r " and s ". Recall however that for theborrower, s < 0, so the term (1 + r) s is negative, and its absolute value represents the loanthat the borrower must repay. Therefore, s " means that the loan is smaller, and r " meansthat the interest rate is higher. It is possible that the total interest on the loan actuallyincreases, so c�2 may decline.For lenders however, we found that income and substitution e¤ects work in opposite

directions of c1 and our result is c�1?. Thus, for the lenders, it is possible that saving decrease,if income e¤ect is stronger than substitution e¤ect and c�1 ". Notice that this �nding isconsistent with the second period budget constraint.

[BC2] : c2 = y2 � t2 + (1 + r) s

We found that for the lenders c�2 ". This is still possible despite s #, because the interestrate is higher.To summarize, our analysis of r " reveals that higher real interest rate must increase the

saving of borrowers, but it does so for only for those lenders with substitution e¤ect strongerthan the income e¤ect.

3.5 Changes in taxes and Ricardian equivalence

We have already analyzed the impact on consumers of the changes in incomes y1 and y2. No-tice that our analysis also covers the changes in t1 and t2 since the lifetime budget constraintis

c1 +c21 + r

= y1 � t1 +y2 � t21 + r

So an increase in y1 by $1 has the same impact on the budget constraint as a $1 decrease int1, and an increase y2 in is just like a decrease in t2. There is however an important resultin public �nance �the Ricardian equivalence theorem, which challenges the e¤ectiveness oftax stimulus.

15

Theorem 4 (Ricardian equivalence). If the present value of government spending remainsunchanged, then changes in the taxes do not a¤ect the households� optimal consumptionchoice (c�1; c

�2).

Proof. The government budget constraint is

G1 +G21 + r

= T1 +T21 + r

= N � t1 +N � t21 + r

Thus,

t1 +t21 + r

=1

N

�G1 +

G21 + r

�We see that any changes in t1 and t2 must be such that the present value of taxes that theconsumers have to pay remain constant. This means that the consumer�s budget constraintremains unchanged,

c1 +c21 + r

= y1 +y21 + r

��t1 +

t21 + r

�;

since the last term on the right hand side (the present value of taxes) is unchanged. Thisimplies that the optimal choice of consumption (c�1; c

�2) for each consumer will remain un-

changed.Notice however that the saving decision of consumers will change, and the aggregate

saving can change as well. To see that recall that s = y1� t1� c1. If the government changesthe taxes (t1 and t2), then since c�1 and y1 do not change, the saving must change by theamount of the change in t1, but in the opposite direction. More formally,

�s = �y1|{z}0

��t1 � �c1|{z}0

�s = ��t1

So if the government reduces the taxes in the �rst period for each consumer by 1 unit, thenthe consumers will increase their saving exactly by 1 unit.

3.5.1 Discussion:

The Ricardian equivalence theorem is a useful starting point for thinking about the e¤ects ofgovernment de�cit. Governments can �nance their de�cit by taxing people or by borrowing(i.e. issuing debt). However, the government must eventually pay the debt by raising taxesin the future. The choice is therefore between "tax now" and "tax later". Our simpleframework suggests that from the consumers�point of view there is no di¤erence between�tax now�or �tax later�. What matters for the optimal choice of consumption is the presentvalue of the lifetime taxes, t1 + t2

1+r, but not the speci�c magnitudes of t1 and t2.

It is useful to list the assumptions of our two-period model, which are responsible for theRicardian equivalence theorem, and may not hold in the real world.

1. We assume that all the households are taxed equally. In the real world it could bethat the tax burden is not shared equally, so that tax policies will have an e¤ect onthe distribution of wealth in the economy.

16

2. in the model, the same people who receive a tax cut are the ones who have to pay thegovernment debt in the future. In the real world the government can postpone the taxincrease until long in the future, when consumers who received the tax cut are eitherretired or dead. In this case, the government tax policy will involve intergenerationaltransfer.

3. In the model the taxes were lump-sum. If we change this assumption and let the taxesbe a fraction of income and also tax the interest rate earnings in the second period,then the timing of taxes will matter for the optimal choice of the household. To seethis, notice that if the government taxes the interest earnings at rate tr. Then theslope of the budget constraint becomes � (1 + r (1� tr)), so if the government changesthe timing of the taxes, the household�s budget constraint will necessarily change.

4. Finally, in the model consumers can borrow or lend at the same interest rate as muchas they please. If we relax these assumptions, the timing of taxes would a¤ect theoptimal consumption choices. A simple example can illustrate why. Suppose that someconsumer is not allowed to borrow, so he is forced to consume his endowment. Changesin taxes will change the consumer�s endowment, and therefore the consumption in bothperiods will change.

3.6 Appendix: Solving the consumer choice problem with Cobb-Douglas preferences

Suppose that the utility function has the form U (c1; c2) = ln c1 + � ln c2, where 0 < � < 1.This is a version of Cobb-Douglas preferences. The coe¢ cient � is a weight on the utilityfrom consumption in the second period. The greater � is, the more patient is the consumer.The consumer�s problem that we need to solve is therefore

maxc1;c2

ln c1 + � ln c2

s:t:

c1 +c21 + r

= y1 � t1 +y2 � t21 + r

This is a standard problem from micro foundations. Nevertheless, we solve it here using theLagrange method. The Lagrange function is

L = ln c1 + � ln c2 � ��c1 +

c21 + r

� we�

First order conditions:@L@c1

=1

c1� � = 0

@L@c2

=�

c2� �

1 + r= 0

Thus the familiar condition of MRS = jslope of BCj isc2�c1

= 1 + r, or c2 = � (1 + r) c1

17

Plugging this into the budget constraint gives the demand for c1:

c1 +� (1 + r)

1 + rc1 = we

c1 (1 + �) = we

c�1 =1

1 + �we

The demand for c2 is therefore

c�2 =�

1 + �(1 + r)we

Notice that you could �nd this demand right away, by recalling that this consumer spendsa fraction 1

1+�of his lifetime income on c1 and a fraction

�1+�

of his lifetime income on c2. Itmakes intuitive sense that the higher the relative weight on a particular good in the utility,the greater is the fraction of income spent on that good.Substituting the expression of we in the demand gives the demand for c1 and c2:

c�1 =1

1 + �

�y1 � t1 +

y2 � t21 + r

�c�2 =

�

1 + �(1 + r)

�y1 � t1 +

y2 � t21 + r

�The saving is then

s = y1 � t1 � c1

s = y1 � t1 �1

1 + �

�y1 � t1 +

y2 � t21 + r

�s = (y1 � t1)

�1� 1

1 + �

�� 1

1 + �

�y2 � t21 + r

�s = (y1 � t1)

��

1 + �

�� 1

1 + �

�y2 � t21 + r

�Notice that higher interest rate implies lower consumption in the �rst period, higher

saving, and higher consumption in the second period. This makes intuitive sense, because1+ r is the relative price of current consumption in terms of future consumption. If interestrate goes up, the consumer will substitute future consumption for current consumption andtherefore will save more in the �rst period.Also, the higher the current net-of-tax income is, the greater is the saving, and the higher

is the second period net-of-tax income, the lower is the saving. This makes intuitive sense.If the current income is relatively high, we would like to save more for the future, and if thefuture income is relatively high, we would like to save less for the future.Finally notice that an increase in y1 by 1 unit will increase c1 by less than 1 unit (by

11+�

to be precise). The saving will increase by �1+�. This example therefore illustrates the

consumption smoothing result, which we derived from general preferences earlier.

18