Becker, Judith

-

Upload

villaandre -

Category

Documents

-

view

226 -

download

0

Transcript of Becker, Judith

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

1/31

ulepssuppmBpol?Tae3qsouauuJauoeupsSpseouuuoydsaqsd1nIuuqleuSeeoqrtFo JopuJoPmaPSaPs3qrSsadxPeoPsou[apaeodeoJanu-ueaosngPJp{0p^s?daqppq

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

2/31

128 EXPLORING TH E HABITUS OF LISTENING

In this chapter, will presenta theoretical rame for the cross-culturalexplorationof music and emotion, provide specificexamples,and concludewith a sectionon thepossibilityof conjoining humanistic and scientificapproaches'

6.t CurrunALLY TNFLEcTED LrsrENrNGStudieson music and emotion conductedby Western scholarsand scientistsnearlyalwayspresume a particular image of musical listeners:silent, still listeners,payingcloseatiention to apieceof music aboutwhich they communicatethe tlpe of emotionevokedby the piece o an attendantresearcher.Communication of the emotion maybe immediate in a laboratory setting,or retrospective, ecalling he emotion after themusical vent .

What is wrong with this image?Nothing, if the intent is to describe he affective esponseso decontextualized er-

for-u.r..Jby middle-classAmerican or European isteners istening to music whileseated uietly.The aboratorysituationmay reflect he habit of many currentWesternlisteners, ossiblyevenmore sonow than in thepast,assomuch musical istening akesplaceattached o headphones ather than at live performances.Silent, still, focusediirt.r-ri.rg s also he habit in some other musical traditions' notably the north IndianHindustani'classical'tradition, where one sitsquietly, ntrospectively isteningto thegradual developingfiligree of the musical structure of a raga,played' perhaps,on aIitar. Thoughts and feelingsare turned inward. The setting s intimate, conducive ointrospectionand a distancing rom one's ellow listeners'

But if the intent is to delineatesomething more generalabout the relationshipsbetweenmusicaleventand musicalaffect, he imageof an inwardly focused, solatedlistener s nadequate.This portrayalof listenerand isteningpresents setof unexam-ined ideologiesand presuppositions hat would not apply for most of the world' Theunaskedquestions nclude:What constitutes'listening'tomusic?What are he appro-priatekinds of emotions to feel?What kind of subjectivity s assumed?Who is

t that is'having'the emotions?How is the event ramed?

Antlropology and ethnomusicologyhave contributed to the study of music andemotion an expandednotion of the possible elationshipsbetween he musicaleventand the listener,and the degree o which affective esponseo musicalevents s cultur-ally inflected.Performancesand listeners ind themselvesn a relationship in whichthey define eachother through continuous' interactive,ever-evolvingmusical struc-turesand istener esponses.Meaning residesn the mutual relationshipestablished tany given moment in time betweenparticular listenersand musical events.A groupof liiteners developsa 'community of interpretation' (Fish, l98o), not necessarilyuniform, but overlapping in some salient features.when presentedwith a musicalevent, his community of interpretationwill approach he music with a pre-givenset

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

3/31

usqFeopu-qeBup8pse1Sddpee(sqsoPusPSseP?saJaeqeppa$usIeseSapq;xdud1ygulopodnue 'alo8oueJlp,yuudpeleouosl?uu

lqaeosBsolu8peusane-Js3u(uSsueleoeueneaueepdS'spaSwo1as1aeSsdss1'u.BApl[quSeqpqlefno8esuJaBu&saaappOd'94duaSd'4rue1aaaJaedaa

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

4/31

relativelytereotypicalithinagiven ociety, ourdi u(1977,p.7z)proposedhe ermhabituso do he heoretical ork ormerlycarried y heword ,curture,:The structures constitutive of a particular tlpe of environment (e.g. he materiai conditions ofexistencecharacteristic of a classcondition) produce habitus,systels of durable, transposabledispositions' ' . that is, as principles ofthe generation and structuring ofpractices and represen-tations which can be objectively 'regulated' and 'regular' without in"ury *uy u.ing the productof obedienceto rules, objectiveiy ad"aptedo their goalswithout presupposing a conscious aim-ing at ends or an expressmastery ofthe operations necessary o attain them and, being all this,collectively orchestratedwithout being the product ofthe orchestrating action ofa conductor.Bourdieu (ry77,p. zr4, I goeson to definewhat he meansby dispositions:The word disposition eems articularlysuited o expresswhat is coveredby the conceptofhabitusdefinedasa systemof dispositions.t expressesirst the resultof an organizing ction,with a meaningclose o that of words suchasstructure; t arsodesignaesa way oJbeing,ahab.itu-altate especiallyf thebody)and, n particular, predispositiZn,undency,ropensity,or inclination.Habitus is an embodiedpattern of action and reaction, n which we arenot fully con_scious of why we do wfa.t we do; not totally determined, but a tencrencTo behavein a certainway. our habitus of listening s tacit, unexamined,seemingry ompretely'natural' 'Welistenin aparticularwaywithoutthinkingaboutit,andwithoutrealizingthat it even is a particular way of listening. Most of olr stylesof listening have beenlearned hrough unconscious mitation of thosewho surround us and with whom wecontinually interact.A habitus of listening suggests ot a necessity or a rule, but aninclination, a dispositior to listenwith a particular kind of focus, o expect o experi_enceparticular kinds of emotion, to move with certainstylizedgestures, nd to inter_pret the meaningof the soundsand one'semotional responsesl the musicalevent nsomewhat (never totally) predictable ways.scholar, *orkirrg *ithin the disciplines ofanthropologyor ethnomusicology lpically assumehat the sianceof the istener snota given, not natural, but necessarilynfluenced by place, ime, the sharedcontext ofculture,and the intricate and unreproduceabledetailsofone,spersonalbiography.-Theterm i haveadapted rom Bourdieu, habitus of listening,underlines he inter-relatedness f the perception of musical emotion and learned nteractionswith oursurroundings. Our perceptions operatewithin a set of habits gradually establishedthroughout our livesand developed hrough our continual interactionwith the worldbeyondour bodies, he evolvingsituation if being_in_the_woilcl.

13 0 EXPLORING TH E HABITUS OF LISTENING

6,2 EvrorroN As A cuLTuRAL coNSTRUcrBut recognitionof the fact that thought is always ulturallypatternedand infusedwith feel-ings,which themseiveseflecta cuiturallyorderedpast,suggestshat ust as houghtdoesnotexist n isolation rom affectiveife,soaffect sculturallyorderedand oes not existapart romthought. Rosaldo,984, . 47)

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

5/31

luqJpeea3q-seqoiuW(4e9loppeaadI-aoeuMs.BgmaJmdraa(dgpopra.

'sdpsse'

snpspsaaesprrp ra

sa.[A1u.a.p,uleeueer ,uuqa

JeuyuA apun1aou"" y

yqp1SpIEsaosu ''urpeuie" poaoog

lupr pppueeopalqd Beuaseslaa

'sluqu&ugeuasqlapreueepoasrroror13T pplua

",o sewuoJp -Qp

"aqnar''ep1sqaJsp

aatuaeoa3sqSpaBalo"d Iuoe

'e'pulueee

'onp-Iap'aqaoqulunapap&e,eoo(1q

'urrun sseunaqdeppd 'da

8plaspe -8qsasoupoupu_ 'Pdep

.leq1Ja1l :oudmeoo

-eoulpnsJUT

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

6/31

732 EXPLORING THE HABITUS OF LISTENING

stagesettings,garbs,and appearances. he'desires and passionsof men'have cometo be seenas rzofproducing identical 'inward motions'. Partly through the cumula-tive effectsof works by cultural anthropologists writing in the r97os (Geertz, 1973,p. 36;Myers r97g), he r98os (Ler,y,1984;Ltttz, 1986, 988;Rosaldo,1984;Shweder&Bourne, 1984), he r99osand beyond (Harkin, 2oo3,p. 266;Ilvine, ry9o;Lutz & Abu-Lughod, r99o; Schieffelin, 99o), scholarswho have championed the concept of thecultural construction of emotion, social scientistsand psychologistsare ncreasinglysensitive o the cultural component in the categorizationof, the interpretation of, andthe expressionof emotion (Davidson, r99z; Ekman, 1980,p. 9o; Ortony et al, 1988,p. z6; Russell,tggra, 99rb).

If we acceptLeach'sversion of the uniformity of human passions,we condone thesilencesmposed upon subalternsof all times andplaceswhose eelingswereassumedto be somorphic with thoseofthe personswho controlled he writing ofhistory, and weignore the developingbody of datasupporting the cultural inflection of the emotions.Ifwe accept he deaof the socialconstruction ofknowledge, of morality, and emotion,we seem o be abandoning he ideaof a human nature,a bond of mind, emotion, andmeaning that enfolds us all, and binds us to one another. We may alsobe in dangeroflosing sight of the individual ashe or sheslips nto the constructedconventionalityofcultural appearance, ehaviour,beliefs,and desires nd disappears ltogether.Personsmaybecome exemplars,nstances f this or that cultural model.

I would like to propose hat both approaches ave ncontrovertible empirical sup-port, and that rather than choosesides,we need to accept he paradox that, in fact,we cannot do without either perspective Finnegan,2oo3;Good, zoo4; Hinton, 1999;Needham,r98r; Nettl, 1983, . 36;Shweder,1985;Solomon, 1984).Cultural differencein the expressionof, the motivation for, and the interpretation of emotion in rela-tion to musical eventshas been persuasivelydemonstrated over and over again; forexample, n S outh Afr ica (Blacking,1973,p.68), Liberia (Stone,1982, . 79),Brazil(Seeger, 987,p. z9),New Guinea Feld,1982, . 3z),Peru (Turino, ry93,p.82),SouthIndia (Viswanathan& Cormack, 1998,p. zz5),Java Benamou,zoo3), Arabic music(Racy,1998,p.g9), Australian aboriginal music (Magowan>2oo7, pp.7o-rc2), andcountry music in the United States Fox, zoo4, pp. t5z-9t). Likewise, the fact that mostof us can,with experience nd empathy,come o understanddiffering expressiveeac-tions to different kinds of music as easonable nd coherentdemonstrates ome evelof commonality and universalityin relation to both music and emotion. It maybe thatwe come into the world with the full range of human emotional expressionavailableto us (Geertz,7974,p.249). hrough continual patternsof interaction with (primarily)close amily members n the early years,we developparticular patternsof emotionalfeelingsand expressionsn relation to the eventsof our lives.For the most part, habitu-ated responses nd actions delimit the range and tlpe of any one person'semotionalresponses.Yet, it would appear that we can imaginatively enter into a much widerpaletteof human emotional possibilities.We need o make aHegelianmove and tran-scend he dichotomy betweenscientificuniversalismand humanistic particularityandembraceboth asnecessaryo the studv of music and emotion.

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

7/31

JS8s1slspeeaasJwpuss(derudoJaJ

:d1o-s

'sDXresaspIspqqtpeuusJa-pJampuaa

'qzepqJlo'8

^u us.,e.J5T .ereSseusdpupdasoJa.8aerpo1asr

:IpJoauqeJe&uareasluee'aa{Nsua@6o'agaeSqpdouspuopJpsapeerssalaospaaa'zd9'uqud1eau6d5'JaJeaosprBs.pasqols,es8guJesa(d1a)

'saaaslppg1sppo1fanes3ouaa'3syaSsaaqSad1pq1 -s

JloranaSaa.arNg

9

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

8/31

EXPLORING THE HABITUS OF LISTENING

theworld appearso us,assolidas his ocalizationmay seem'and anchoredn the verynature

of the hum} agent, t is in largepart a featureof our world, the world of modern,westernp""pf. The ocilization is not i orrirr".rutone,which humanbeings ecognize sa matterofcourse,as hey do for instancehat their headsareabove heir torsos'Rather t is a functionof a historically imited modeof self-interpretation, newhich hasbecomedominant in themodernwest andwhich may ndeedspreadhence o otherparts of the globe'but whichhadabeginning n time and space ndmayhavean end' (TaYlor,1989, ' rn)I t isa lmostatru ismof.o, ' t . -porarycul turalanthropologythat thenatureofsubjectiyity, of the senseof self, varies cross-culturally' This is a profoundly anti-intoitirr. notion, and one that has strong objectors in philosophy from St Augustine(vonCampenhausen,1964,ptp.zz6-7)toBertrandRussell(Seckel'1986'P'q6)'Aswiththe issueof 'emotion', io ,uy tt ut subjectivity is culturally constructed seems o denythe basichumanity of mankind. Yet differencesseem o remain in how personsthinkof themselves n relation to other persons' and these differencs are often markedlycultural (Fajans, zoo6; Schieffelin, r99o; Shweder& Bourne' 1984'p' r9r)'

6.4 PnnsoN AND EMoTroN rN THEHABITUS OF LISTENING

Theparticularsubjectivityof the isteners escribedn psychological tudies'hepro-,o-rypi.a western, middle-classistener o music, s ikely to be somevariantof thefollowing:an individual with a strongsense f separateness'f uniquenessrom allotherpeisons,an ndividualwhoseemotionsare elt to beknown n their entiretyandcomplexityonlytohim or herself,whosephysical ndpsychicprivacyisreasured' ndwhoseemotionalresponsestoagivenpieceofmusicarenotfeltto.beinrelationtoanythingoutsidehis or her own particularself-historyandpersonality:The emotion'fo, .rr,b".longso the ndividual,not to the situationor td relationships' motion s heauthenticexpression f one'sbeing,and s, n somesense, aturaland spontaneous'Theemotion s nterior,muyo, -ufrrotbe sharedwithanyoneelse,ndmaybeaguide

to one,snneressence.eo ireitler ir993,p.+8) aswritten boutonewayinwhichthisstyleof subjectivity an elate o listening o music:It is that nteractionf theselvesf the istener ith thosen themusic-no' betterput: heawarenessftheself selves)n themusichroughts(their) ntglSaionwitlrthe istener'self-that nterestsmehere;musical ommunicationsa unctionof the nteraction f identities'Thedifferingidentities fthelisteningsubjectandthoseprojectedbytheusicbecomethe ocusof nterestandaffector Treitler.OnecommonvariantofthisWestern ind ofsubjectivitywhile istening o music s to identiff with the different dentityprojectedbythe music.Listeningtolusicoffersthe opportunityto temporarilybeanotherkind

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

9/31

lep$uusmsqs(ed9Jzgnsulunsrn'BJuuespIB-usp

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

10/31

13 0 EXPLORING THE HABITUS OF LISTENING

seems oncordantwith what I, or most readersof this essay,might feel of performingmusicians:A raga s an aestheticrojectionof the artist'snner spirit; t is a representationf his mostprofoundsentiments nd sensibilities,et orth through onesand melodies . . I mayplayRagaMalkauns, hose rincipalmood lrasa]s veeraherorc), ut I couldbeginby expressingshanta serenity] nd karuna compassion]n the alapand developnto veera heroic]andadbhuta astonishment]r even audra angetl n playing he or or hala.The inner spirit of the artist, functioning within culturally constructed categoriesof affect, s made manifest in the outward expressions f his musical presentation.Bringing yet another dimension of similarity to the two listeningsituations s the factthat emotion (rasa) experiencedn listening o Hindustani classicalmusic s distancedand impersonal.One can feel the emotion without the troublesome mmediacy andconsequences f an emotion that compels action (Abhinavagupta in Gnoli, 1968,pp.Sz-s; Masson & Patwardhan,1969,p.46).JuneMcDaniel (1995, . 48), writing ofrasointhelndian province of Bengal,uses he metaphor of the glasswindow separatingthe experiencer rom the emotion while still allowing a clearview:Bhava s a personal motion; asa s an mpersonal r depersonalizedmotion, n which heparticipants distanced san observer.Why is a depersonalizedmotionconsidereduperiorto a personal ne?Becausehe aesthetean experiencewiderangeof emotions etbe pro-tectedrom theirpainfulaspects.motion s appreciatedhroughaglass indow,whichkeepsout unpleasantness.hough heglasss clear,husallowing unionof sortswith the observedobject, he window is always resent,hus maintaining he dualism.The following description s aWestern mirror-image of the classicalndian experienceof rasa;When people isten,say, o 'Questi campidi Tracia' rom Monteverdl'sOrfeo . . they donot directlyperceivehe anguish nd guilt of the wice-widowedinger. istenersnlyheararepresentationitalicsmine] of the wayhis voicemoves nder he nfluence f his emotions.Nevertheless,his can give istenersmportant nsights nto a tlpe of emotional esPonse.Monteverdiskillful1y isplayshe contortions hroughwhich Orpheus's oicegoes.Whenlistenersnow how a voicemoves nder he nfluence fan affect,heyaregiven ifthey arefamiliarwith theconventionsf themusic, ndotherwise ualified) n mmediate emonstra-tion of something bout he affect. goodperformance f this aria mmediately emonstratesto a sensitiveudienceomething boutwhat t is ike o feelguilt, emorse' nddespair'(Young,1999,P.48 )In both the Hindustani and the Western classicalistener,an emotion evokedby lis-tening to music canbe contemplatedwith a certaindeliberationand calmness.But atsomepoint the congruencies etween he habitus of listening of eachbreaksdown. TheWestern observermay well, asTreitler suggests, e involved with comparing identi-ties,or with constructingamore glamorousself n relation to the music heard, or withcontemplating'what it is like to feel guilt, remorse,and despair'.The Indian, how-ever,may be performing a very different act,a somewhatstrenuous eligiousexercise,a kind of refining of emotional essence, distillation of his or her emotion that willlead o a transformation of consciousnesso a higher level of spirituality. Listening o

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

11/31

,enpuesa1nsouuesaeueeUsuae.ansUeuuPSJp1ouspuIuu$usunJnuauuP.oSJeauPoq,punos

TNg

'dBPepauaJpSJeoas-ueSuJJa3-adJaausaquuops^;uSDusP peu

leoolaqfuueJsS-uIeeSd'1dJaauume3EopsouanJaeJsuaorSV(s_^

'aSSoqmadeasuopapnPLPaesa.pqc'dauaJuoaqafaseaopqnuaouesleueoP,psepadPsaPsa1rsnudopaues1

:SoasseepareoSBsuuuaues

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

12/31

138 EXPLORING TH E HABITUS OF LISTENINGreferenceo theaffective,nterpretivecomponentof arousal.Theymayoccur n rela-tion to sexual ctiviry to exercise,r asa resultof drugsor alcohol,aswellas o musicallistening.In his famousand controversialheory of the emotions,william |amesclaimedthat the physiological omponentof arousal s primary and precedeshe interpreta-tion of thesubsequentmotion(|ames ggo/r95o, p.442-g5).The'feering,f angersthe feeling hat results rom an angry acialexpression,odily stance, hallowbreath-ing,etc.Anger, he emotion,r, accordingo fames,what onefeelswhenenactinghisdisplay.Following ames,but with much moreknowledgeof the neurophysiology femotion'Damasio uggestshat the erm emotion'shouldbeapplied o ANS aroirsal,and that 'feeling' hat follows emotion' shouldbe applied o tir" .o-plex cognitive,culturally nflected nterpretationof 'emotion' (Damaiio, t999, .zq). BoththepolishGrotowskischoolofacting Grotowski,1968) nd he ndianrathakali theatreradition(Schechner,988, . z7o)seemo support he heories ffamesandDamasio.Traininga Kathakaliactor,or aWesternactorof the Grotowski radition,begins nthmimesil,recreatinghebodily gestures f an emotion,not with delving nto Jne'smemories orecreate feeling', s n Stanislavsky'schoolof 'method'aiting (Stanislavsky,95g,p.1977).

In any case,t is usefulanalyticallyo separate hysiological rousal .emotion, orfamesand Damasio) rom the more cognitiveconcept'feeling'.Unlike feelingshatdirectly elate o judgements ndbeliefsearnedwithin aculturalcontextand hat relyupon linguisticcategorieshat areoften ncommensurable crossanguages,rousalis moreclearlyauniversal esponseo music istening.Combinedwith aconcentratedreligious ocus,musicalarousal ancontribute o extreme tates f emotion.Happinesssthe emotionmost requentlyassociated ith music istening,andmayconstituteoneof the universals' f cross-cultural tudies fmusicandemotion.Fromthe'polkahappiness'ofhe polish-Americanparties f chicago Keil,1987, .276),to the lKungof the Kalaharidesert,Beingat a dancemakesorir heartshappy'1ratz,t982,p.348), to the Basongye f the congo who 'makemusic n order to ie huppyi(Merriam, L964,P.8z), to the extrovert"Jloy of a Pentecostalmusicalservice Cox,1995 musichas heabilityto makepeople eelgood(see lso chapter4,thisvolume)The happiness f listening o music,howeverone construes appiness,s in part thesimple esultof musicalarousal.Wetend o feelbetterwh.nr.. ur" -osically arousedand excited.Theemotionmaybeattributed o someotheraspect fthe eventsuchasthe ext or our own dancing;nonetheless,hemusicalstimulationshouldnot be mini-mized.Musiccanbeacatalystor a changing tateof consciousness.The following section ncludes hree examplesof extremeemotion contextuallysituatedwithin a religiousceremonyn which music s an essential lement;all threearesitesofthe author's ieldwork.

6.5.r Music and ecstasy:he SufisThe strongest ersionof happinessn relation o musical isteningand an exampleofextremearousalsecstasy.SeeRouget, 9g5,or descriptions f musicand rancing n

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

13/31

deqaarqpe{eeeuaalenJarqeBaduu

tnap2'qVqlpppe 3aenas1pu'1apeld

supsgoJeuole.aaaduSrpeuaoSo,pB'S3rqeudapJaeBe u

lpaJ?upseaaseppa 'uBleJJsoaqdrBxr dpa

IaSraraapB a''e.epepnupB

;ursaFuSsgv(urqeeso u's

2 SpsqSupoleadplees aleoua

a'd'9,,salueaoLsasrauag 's

rsaaqpeens Saeadesrslne,eoa

r?uuo,paeadu SpdSua3'S'Ssqsoaas -S

'8oSIqqqMueou upluapqdsoeq -sSr

'euuulap?,g(Sd

'1uossaaep douuuppoedeasupd 's

3paIaqfnqsee 'dqaeusppcdpasq$u -?u

1ugaelqpqusuJu'eP

'uuuu&usp81adpneeg&aeepusrppBJsgae'useJs{gsulB?edauqppasou$a-s3pe(spa6

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

14/31

EXPLORING THE HABITUS OF LISTENING

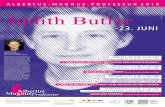

Fig.6.1 Dancing ufis. rom he Divan Bookof poems)f Hafiz Walters rtGal lery,al t imore).

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

15/31

qAo'

be6suZg6

(ueq6u11epuopd[a]uaeeSeSnaest>L1iuea11do1ssiqruSa3ea1eqodd1suseasuauedeu

:aSuu9auaaSuqqasqaeO1Jpa(Jp-guausSd-ogsSd'6ugIJN1upadJepSruepeueppae1leSpNpdaquaendaepum'upeusuuJe&'se-esaqo

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

16/31

r42 EXPLORING THE HABITUS OF LISTBNINGNeither the trance,nor the ceremony,nor the pacificationof the witch can happenwithout thegamelanmusic Figure6.3).The habitusof hearingof I WayanDibia uponencounteringRangdawould have o include a descriptionof not only the gamelanmusicand hepresence f the witch, but a complexofbeliefsabout he negativeorcesof the universe, heir effectsupon human communities, he embodiment of theseforces n the divinewitch Rangda, nd hemethodsbywhich shemaybecontainedandcontrolled.His own emotion,culturally constitutedbut felt interiorly, is a necessarycomponentof the maintenance f community well-being.His murderouspassion aslittle to do with an nteriorizedself,with the dentity of I WayanDibia. His rage, n partmusically nduced, s n the service f his community.Like the Wolof griots,musicalemotion for the trancer n a BalineseRangda xorcism spublic,situational,predict-able,and culturally sanctioned.

Fig.6.3 Musical ranscription sf the encounter'heme rom aRangda/Barongitual.

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

17/31

uuSpuseqeopperX fspuu"ppa aauSuJ

uuuaBeJSpueuapaueI '@

a'5xmp1eI,p!SuSupaeura.l1paseeLluaosssaepeu4poopsassrlurepauurpuBeeIBauasaJaalesepu-ssaprsIueeIu-psgaeuaporeoas'Be&ude -ue

o

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

18/31

I4 4 EXPLORING THE HABITUS OF LISTENING

similar to the Sufi istenerand he Baline ebebutenttancer,or aPentecostalistenerthe habitus of listening involvesa scriptedsequence f actions,emotions' and inter-pretations.Within each of these hree scripts,musical,behavioural, and emotionaleventswill occur within a certain predictable frame' Simultaneously' each ndividualeventwill be unique and non_repeatable.The listenersto aWolof griot, anlndian sitarplayer ,agroupofclawwal i ' i "gt t ' ,aBal inesebebutentrancer 'oraPentecostalwor-shipper have al l develofed hailts of mind and body in response o specificmusicalevents.Thesehabitsareacquired hroughout their life experiences f interactionwithothers in similar situations. The emotions areprivate andpublic,interior and exterior,individual and communal.

6.6 Musrc, EMorroN' AND 'BETNG':coNJOTNTNG ANTHROPOLOGY'

ETHNOMUSTcoLoGY' PSYCHOLOGY' ANDNEUROPHYSIOLOGY

It seems lear o this author that a common ground needs o be exploredbetween hemore humanistic,cultural anthropologicalapproachand he more scientific,cognitivefry.frotogl.ul approach (seealsoHinton' 1999'and Cross' 2oo8' fo r a similar view')I see he bringing together of the scientificand cultural approaches o the study ofmusicand emotion asone of the greatchallenges f our fields.while the stylesof argu-ment and the criteria for evidencemay remain distinct, the conclusionsneed to becomparableandnotincommensurable.Bothdisciplinaryareasmayhavetomodifrsomeof their establishedscholarly practices n order to communicate effectivelyacrossdisciplinaryboundaries'

6.6.r Single-brain/-bodypproachesFor those approachingthe study of the emotional effectof musical listening on thebrain,theunitofanalysisisusuallythebrain/bodyofasinglelistener.Fromtheearlystudiesof music and the brain such as Neher's earlywork in the r96os (Neher' 196r'196z),analysingthebrainrhyhmsofsubjectslisteningtodrumbeatsinalaboratory,to the more recentworks of clynes (1986),wallin (rggr), Blood and zatorce (zool)'peretz(zoot), Menon and Levitin (zoo5), and many others, musical scholarshaveadopted he scientificmodel and studiedsinglebrains/bodies n isolation' Studies n

-rrri. .og.ritionhave argely ollowedthe empiricalmodelsof cognitivestudies n gen-

eral n their efforts o -Ja.ittr.algorithmsof singlebrainsprocessingmusic (Bangert'

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

19/31

's4pSn{ua

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

20/31

746 EXPLORING TH E HABITUS OF LISTENING

What is a supra-individualbiologicalprocess?n Nirflez'sGggz,p.r55)words:By supra-individual iological rocessesmean hoseprocesseselative o life that occurata levelbeyond he autonomous eingsone s studying . . The processesnterveningn thespread f a cholera pidemic rean example f supra-individualiological rocesses;hephe-nomenon s manifestedn individuals . . but it is realizedhroughbiological rocesseshattakeplacebeyond he sick ndividual . . .Let me further llustratewhat I meanby supra-individualiologicalrocesses ith anotherverysimpleexample: peech ccents . . Although a brain is necessaryor a particular speechaccento occur) san solated rgan t does ot determinet. Accents remodes f producingnoises'during speech hosedistinction s madeby an observermakingreferenceo coliectivephenomenaatsupra-individualevels). onetheless,speechccentsstilla ivingphenom-enon,as t is realized n the ontogenyof some iving beings.Accents-aithough manifestedin individuals-have to do with biologicalprocesseshat are reahzed t evels hat gobeyondthe individual,and that explainwhy speech ccents re neitherrandomlydistributedamongpopulations or are heygeneticallyetermined.

A linguistic accent can be attributed to a particular individual, but it is not thecreation of that individual, but rather, results rom historical processes f languageimitation and repetition. A person may'have' an accent,asa person may know howto play a drum, but neither the languageaccent,nor the knowing of how to play thedrum can be attributed solely o an individual. To play the drum correctly or effectivelymeansrepeating he sounds n a culturally acceptablemanner. Likewise, emotionalreactions n musical situations are experiencedwithin individuals, but the musicalexpressionshat trigger those emotions are framed within a historically determined,culturally inflectedcomplex of musical conventionsknown to musiciansand istenersalike.The unit of musiciansand listenerscan be thought of as a community of inter-pretation' (Fish, 98o), as a singlebiologicalprocessoperatingwithin sharedmusicalhistories.

6.63 Habitusof listening:culture and biologyNriflez is not alone n his appeal or cross-subject rain studies seealsoBecker,zoo4;Benzon,zoot;Foley,1997; reeman) 0oo;Maturana&Varela,1987; arela,Thompson,& Rosch, 99r). ntegratingthe nsightsofphenomenologywith thoseof contemporarybiology has brought forth fresh ways to think about human interaction asmutuallyconstituting organisms.The interactions of groups of people n communally sharedsituations s often called communication', invoking the image of something trans-ferred ntact from oneperson'smind to another person'smind, or vaguely eferred oas bonding' with no explanationof the how' by which bonding transpires.Wishing toimply something more fundamentallybiological to talk about what are usually referredto as socialor cultural phenomena,I am using the term 'structural coupling' devel-oped by Maturana andV arelaG1SZ)o describeaprocess hat encompassesinglecellorganismsand extendsoutward to includehuman socialgroups, o help imagine whathappenswhen groups of like-minded people are involved in recurrent situations of

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

21/31

'eB(d nlqmuuS.

'@aeBubt96

'aopnuuu-Aaduu1dduaSqIauWueuq '9

auuluuupsueFsu-euusInpFacuoeie

'9aapoSqmg1p se

EeJaoe1 -mseenaa

leppdaeJleuySpSusIuopUJaBr&-quoppl4sleulenqoaeu.d1zannsBpea'auueuISma

'sIpuuuq useu4eo.SFSsusJnan0saasuesBplV

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

22/31

r48 EXPLORING THE HABITUS OF LISTENING

I t \! t/--\ /--\/ \ / \\r\-\_/N.'ll

MFig.6.6Organismsn interaction i th external i l ieu ndeach ther Maturanaft Varela, 987,p. 74).Because f the autonomous nature of the organism, nteractions between organismsor interactionsbetweenorganism and nert environment, called'perturbations,'neverspecifi'what changesmay takeplace n the organism.The organism tself determines'which perturbations are 'allowed', how and to what degreea perturbation will bemodified. Thus, perturbationsnever cause he changesn an organism, hey can onlyinstigateor trigger change.The organism s autopoietic', 'self-creating',and the pro-cess f it s changesare autopoiesis',or'self-creation'. It is not the environment or theinteraction but the organism tself hat'creates' tself.

If interaction betweentwo organisms s recurrent, and if the changes n the twoorganismsare congruent, f they are similar, then the two organismsbecome nvolvedin shared ontogenetic change-they change ogether and become complementary.Over time, cumulative change eads o 'structural coupling'between two organismsas heir internal milieu (including human brains and bodies) become inked throughrepeated nteraction, co-ontogenieswith mutual involvement hrough their reciprocalstructural coupling, eachone conserving ts adaptationand organization' (Maturana&Varela,1987, . r8o).

These changesbecome new domains of knowledge, knowledge gained throughinteractive behaviours, hrough doing. Music listenersas well as musicians undergoa learning process,n which they imitate physicaland mental gestures hat ultimatelytransform both their inner structuresaswell as heir relations o everythingbeyond theboundaries of their skins.Music and emotion arepart of a argerprocessual vent hatincludes many other peopledoing many other things while the whole eventunfolds asa unity that hasbeen organizedand reorganizedover time by small structural changeswithin the participants.

We are accustomed o thinking of biological processes s extending from a singlecell, o multi-cellular organismssuchasa ree, o animals,and to a singlehuman being.When groupsof peopleare acting n somekind of accord,we tend to say hat the phe-nomenon is social,or psychological,or political, not biological. If we think of musicmaking and music istening within aprocesshat may also nclude quiet ntrospection,or conversely,nclude preaching,glossolalia, ancing, or the murmuring of mantras,asal l part of a biologicalprocess hat has had a ong history of 'structuralcoupling', orcontinual self-recreation,we can begin to think of the music, the emotion, and everyother aspect fthe process scontributing to bringing forth the activitiesofeach other,

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

23/31

.aaqpSuuuae1a0'oapndJas-aeupsuupuSa.puOd'9F.oumPpsPAsoopSpaae _sguade1sqeeedoopaBSaaoqe0seopqnodps3a

'su8pelu-p'ppup.BueaIEauoaP;eaepaoasuJoeuleBApueqVuoepespspaJS

'uJqeauF pleu3pppuped,up(9

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

24/31

15 O EXPLORING THE HABITUS OF L ISTENING

PFRFORMER5:L6{ rr}q6 Yitha@Fgo-hi3tg?icleug u.

LISfENER.S:

HKY

M

If

uD

L

"rNI

KX

Fig. .7 Transcript ionexcerpt)f music/part icipantnteractionsn a northIndian uf i i tual f romOureshi ,986, . 171).

6.6.+ What is gainedby claiming hat theseprocessesarebiological?

We may claim that specialmodes of consciousexperience uchasemotional responsesto music listening, an habitus of listening, emerges as a phenoqpic feature of

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

25/31

'su

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

26/31

Appadurai,A.(rqq6).Modernityatlarge:Culturaldimensionsofglobalizatiorr.Minneapolis,MN: UniversitY f Minnesota ress'Balasaraswati,. (tg8t). fhe ar t of bharata atyam: personal tatemnt 'n B' T'Jonesed')'Dance sculturalheritage,, DanceResearchnnualxy (pp' r-7).NewYork:congress nResearchn Dance.Bangert,M. (zoo6).Brainactivation uringpianoplaying' n E, Alte1m1l-ller I' Kesselring(eds),Mr,rslc,motorcontrolanrlthebrain(pp.r73-r88).oxford:oxford-UniversityPress.Barnard,Na. rssl). Advertising: he rhetoricalmperative.n c. Jenks ed.),visualculture(pp. z6-41.London:Routledge'Baxandall,M. (rgl+). folrti"l 'ia experiencen fifteenthcentury talyi A primer in thesocialhistoryofpictorialstyle.New York: Oxford UniversityPress'Becker ,A.L.(1995).Beyondtranslat ion:Essaystowardamodernphi lo logy.AnnArbor ,Ml:UniversitYof MichiganPress'Becker, . f. (lggq).A short, amiliaressay n person' anguageciences'1'229-36'Becker,l.(rS8:).'Aesthetics'inLate2othCenturySchoiarship'TheWorldo'fMusic'25'65-8o'Becker ,J.Qoo+).Deepl isteners:Music,emot ion,andtrancing.Bloomington, IN: IndianaUniversitY ress.Benamou,M.(zoor) .Compar ingmusicalaf fect :JavaandtheWest,WorklofMusic,45,

57-76.Benveniste, . (t'gzt)' Subjectivityn language.n Problemsn general inguisticstrans.M. E.Meek) pp.zz3-3o)'CoralGables' L:University f Miami Press'Benzon,W,L.(zoor) .B, , th,oy, , , ,anvi l . 'Music inmindandcul ture.NewYork:BasicBooks.Bhabha, . K. (rqg+).The ocation fculture' ondon:Routledge'Blacking,J.Ogli.Howmusicalisman?Seattle'WA:UniversityofWashingtonPress'Blakeslee,., & Blakeslee, . (zoo7).Thebodyhasa mindof itsown:How bodymaps n yourbrainhelpyou lo (almost)et'erything effer'New York: RandomHouse'Blood,A. 1. ,&zatofie,n. i. troorl. Iitenselypleasurableesponseso musiccorrelatewithactivity in brain regions mplicated n rewardand emotion' Proceedingsf the NationalAcademYfScience,S'11818-23'Bourdieu,p (rslil. outli"neot'a tieory ofpractice trans.R.Nice) cambridge,uK: cambridge

152 EXPLORING TH E HABITUS OF LISTENING

UniversityPress.Brennan, ., & |ay,M' (eds) D96)' Visionn context:'on sight. ondon:Routledge'Brown,b. E. (rqqr).Humanuniversals'hiladelphia'Chapple,E. D. (rqZo).Cultureand biologicalman:

Historicaland contemporaryerspectitesPA:TempleUniversitYPress.Explorationsn behavioralnthropology'

NewYork:Rinehart& Winston'Cla l- ton,M.,Sager,R. ,&Wil l ,U' (zooS) ' Int imewiththemusic: theconcePtofentra inment and ts signidcanceor ethnomusicology. uropeanMeetingsn Ethnomusicology'7' -75'Clynes,M. (rqs6).When ime s music' n J'Evans M' Ciyneseds)'Rhythmn psychological'--' Iingukticantlmusicalprocessespp' 169-zz$'Springfield' L: C' C' Thomas'Churchland,P.S.( rgs6) .N,"ophi lo 'ophy:Towardauni fedscienceof themind-brain 'Cambridge, A: MIT Press'Condon,W'S.( rqs6) .Communicat ion:Rhl thmandstructure. In} 'Evans&M'Clynes(eds),Rhythm n psychological,inguistic nd musical rocessespp' ss-ll)' springfield'L:C.C.Thomas.Coomaraswamy,A.K.(1957)'ThedanceofShiva'NewYork:TheNoondayPress'Cox'H.(t995).Firefro*'hno,,n'TheriseofPentecostalspiritualityandthereshapingofreligtonin the wenty-firstentury' eading, A: Addison-Wesley'

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

27/31

'$oq@duaun-oIuSp:Mls.

:uaauun:laJapg.

.$E.snloauauuJa;3.

'aw: 'Appapso,a

|.1 .saa: nn

JsmaaaG(Wur .fe 'a6dploapo nt:Uureus.u

'JWataug'ueANSleJVA .

fu pawpu"V'.up

sHA 'o'SlQa;suoa...C '

f:31plaopHqsntupueuBaUSVgH.V .

:..utwntp1aGur'uWu8o.'n .

ud:a 'ulnSpsSupS .

loep lpuapupepo.eo

:'dod'uyo auuepolenpo

'spd 'Up1uuwpo, '$o

{'patouupl7.e'sI.eu

'aSsaauuViO 'sfa:3,Ou) 'o

^:-s.C .guE -us

aeo.GU'o

loupwoaV .s$:'uupQlaaca.@,E .ga

pJua$Taaaennpqr3

r

D

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

28/31

154 EXPLORING THE HABITUS OF LISTENING

Geertz,H. (rgZD.Thevocabulary f emotion:A studyof favaneseocializationrocesses.nR. A. LeVine ed.),Culture ndpersonality:ontemporaryeadingspp.z+g-6+).Chicago,IL: Aldine.Gergen, . J. (rqqr).Thesaturatedelf.Dilemmas f identity n contemporarTfe.New York:BasicBooks.Gnoli, R. (rg68). The aesthetic xperience ccording o Abhinava Gupta. Yaranasi, ndia:Chowkhamba ublications.Good,B. . (zool. Rethinking'emotions'n Southeast sia.Ethnos, 9,5zg-33.Goffman, E. (rSSS).Thepresentation f self n everydayife. GardenCity, NY: Doubleday/AnchorBooks.Goldhill,S. rqq6).Refractinglassicalision:Changing ultures f viewing. n T. Brennan&M. Ia y eds), isionn conrext'.istor icalndconremporaryerspectivesonight pp .17-28).London:Routledge.Goodenough,W. H. (tqzo).Descriptionndcomparisonn cultural nthropology.hicago,L:Aldine.Grotowski,. (1968). owards poor heatre. ewYork: SimonandSchuster.Hall, E. Q977). eyond ulture.GardenCity,NY: Anchor Books.Harkin,M. E.(zoo3). eeling nd hinking n memoryand orgetting: owardan ethnohistoryof theemotions. thnohistory,o, z6r-84.Haueisen,.,& Knosche, . R. (zoor). nvoluntarymotoractivityn pianists voked y musicperception. ournalof CognitiveNeuroscience,j, 786-92.Hebdige,D. (rSSi).Fabulous onfusion!Pop beforepop? n C. ienks (ed.),Vkual culture(pp.96-tzz).London:Routledge.Hinton,A. L. (rqSS).ntroduction:Developingbiocultural pproacho theemotions.n A. L.Hinton (ed.),Biocultural pproacheso theemotionspp. -:Z). Cambridge, K: CambridgeUniversityPress.Huron, D. (zoo6).Sweet nticipation: usicand he sycholog,,f expectation.ambridge, A:MIT Press.Irvine,J. T. (rqgo).Registeringffect: eteroglossian the inguisticexpressionf emotion.In C. Lutz, & L. Abu-Lughod eds),Language nd thepoliticsof emotion pp. tz6-6t).Cambridge, K: Cambridge niversityPress.

James,W. (t89o/t95o). heprinciplesfpsychology,ol .z. NewYork:DoverPublications.Janata,P. (tggZ). Electrophysiologicaltudies of auditory contexts.Dissertation AbstractsInternational. ection : TheSciencesnd Engineering, niversity f Oregon,USA.Jefferson, . (rSS+).Declarationof independencend the constitutionof the Llnited States fAmerica:he exts.Washington, C: NationalDefense ress.Originally ublished776)Jenks, . (ed.) rgqS). isual ulture. ondon:Routledge.Johnson,. H. (rSSi). isteningn Pads.Berkeley, A: University f CaliforniaPress.Katz,R. (1982). cceptingBoilingenergy': he experiencef lKia healing mong he Kung.Ethos,9,348.Keil,C. (1987). articipatory iscrepanciesnd hepowerof music.CulturalAnthropology,,275-83.Kern, S. (t996).Eyesof love: Thegaze n Englishand French ainting and novels, Sqo-t9oo.London:Reaktion ooks.Leach, . (r98r).A poetics f power.NewRepublic,84, ^4.Lerdahl, ., & Jackendoff, . (rg8:).A generativeheory f tonalmusic.Cambridge,MA: MITPress.Levi-Strauss, . (l.962). hesavagemind.London:Wiedenfeld& Nicholson.Levitin,D. J. (zoo6).This syourbrainon musiciThesciencef a humanobsession.ew York:Dutton.

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

29/31

'lH8.puwul:S(.,UN

'9sls.auqps,:qdB.

'sJr :ogpsaQ:ta.G

'0eu 3sul;py.

'$erodotNMpuBoquoualE 'pdpSf '

e;u 'd'$dslussr.

'oErSrpppdVaps..

'a:'a1 q3aee,pqo..

' o:,,:..U' fu

looua'V '9'9utr4.U

'lgaula;ppa:tsa.C

's,pY'aSAW 's

{da..,-aaVuussUAu:squ

'e d:pa.

'du^: -us1aaa4H

'eDqIp.WgN

'srpuIN 'eeauuup:l.('sda:

uolooapa,pgudgsqap'"Ttpluwas,:l '

6lodtl 'dIup'

(fp :aoutaww.

' sueJa.

' .a3(uop1,wus:OaU.Uup,.

S

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

30/31

15 6 EXPLORING THE HABITUS OF LISTENING

o'Neill, I. ogg). Foucault's ptics:The (in)visionof mortaliryand modernity. n c. |enksed.),Visual ulture pp. 9o_zor). ondon:Routledge.ortony, A. , clore, G ! , & collins,A. (rq88).Thecogn"itivetructure f emotrons.cambridge,UK: CambridgeUniversitypress.Patel,A' D. (zoos).Music, anguage,nd hebrain.oxford:oxford universrty ress.Peretz, . (zoor). Listento the train: A biologicarperspective n musicalemotions. nP' N' Juslin& I. A. sroboda eds),Musiconi ,*oiion, n,rory)na-)rsearch pp. 1,,514).Oxford:Oxford Universitypress.Qureshi'R' B' (rq86)' uJimusic f ndiaanrlPakistan:ound, ontext ndmeaningn qawwali.Cambridge,UK: CambridgeUniversitypress.Racy,A. I. (rsss). mprovisation, cstasy,nd performance ynamicsn Arabicmusic. nB' Nettl & M. Russell .3r1. ? the co,ursefperformance: tudies n tt , *orta of musical_ improvisationpp. 95-ttz).chicago, L: univeisiiy of chicagopress.Raffrnan,D. (rSS:).Language, usic,and mind. Cambridge,MA: MIT press.Rider'M' S' ' & Eagle,9' t' ' lt ' (rq86).Rh)'thmic ntrainment samechanismor learningnmusic herapy.n J.Evans& M. crynes eds), hythm n psychotogicaj,rrncuirtl,ora musicarprocessespp. zz5-48).Springfield,L: C. C. Thomas.Rosaldo,M. z. Qgsa).Towardananthropologyof selfand eeling. n R. Shweder& R. LeVine(eds), Culture theory: Essaysn minri, ,ilf, ona emotion tpi ,rzlsrl Cambridge,UK:CambridgeUniversitypress.Rouget'G' (rg8l)' Music^,ald rayce:A theoryof the relationsbetweenmusicand possession_ (trans.B. Beibuyck). hicago,L: TheUniversity f Chicago ress.*":::tl,lj eegra).curture and the categorization f .moiio.,r. isychologicar uuetin, ro,

Russell'' A' (rqqrb).Ti.f":. of a protoqpe approach o emotionconcepts.ournar fer onality and Social psy hotoy, oo, 37_7'.-Schechner, . ( 988 . perfomanci' h,o f .' Lo)ndonRoutledge.Schieffelin,B. (rqqo). ,I:_q:r: an! ylke of everydayife,Linguog, and sociatization f Kaluli^ chi.ldren. ambridge,UK: Cambridge iniversity press.seckel' ' (ed')(rq86)'BertrandRusselln Godand eligion.Buffalo,y: prometheusBooks.seeger, ' (ry8.). \\hy suyasing:A musicat nthroporory f anAmazonian npk.cambridge,UK: CambridgeUniversitypress.Shankar, . tg6'). My musii, y1fe.Ne wDelhi, ndia:Vikas ublicarions.Shepherd'I' ' & Giles-David,l. (ri9r). Music, ext and subjectivity.rnMusicas sociarextpp.rz+-8). Cambridge, A: politypress.shweder'R' A' (rq8s)'Menstrual oilution,soul oss, nd hecomparativetudyof emotions.In A' Kleinman & B. Good (eds),curture and depression:tuiies , ll* ortt roporogy nd,;::;#::,;::,::chiatry of ffict and disorder pp. nz-zt5). s.ft;I.;, ca, university of

Shweder, . A. (rqzq).Rethinking ultureandpersonalityh eory. thos, ,279_3tr.shweder,R' A' , & Bourne,E. i. (rq8+).Does he conceptof the personvary cross-cultur_ally? n R. Shweder& R. Levine (eds),culture theory:Essays n mind, self,and emotion(pp. fs-ss). Cambridge, K: Cambridge niversity ress.slater'D' (1995)'photographyand modirn vision: The spectacle f .natura.lmagic,. nC. Jenksed.),Visual ulture pp. zt81).London: Routledge.small, c. (ryg'). Musicking:Thi-meaniigs of performingori listening.London: wesleyanUniversitypress.Smith, . C. ,& Ferstman, . (rgg6).Knowledge nd the anguaging ody. n I. Smith (ed.),Thecastration f oedipus:Feminism, sycitoanarysis,ncl he will to power (pp. sz-zg).ewYork:New york Universitypress.

SrS

SS

S

SSSTiTI

TTVi

VVl

vc\A\ ,\AY

Z

-

7/29/2019 Becker, Judith

31/31

'sdadasnPa'4SBUuequadn1S4 's

JWa 'anuuuwS'34'1

'wunlooaJaaa68 'o'hsna'

)0uePuaeugg8In1A'9SIUupSaT

'un:JIuCA'eAA'P'su:ugopsaus

lop1&'1ml'15'uAT :ysqma

loa9'uu'soodopo

aus:nloa,wIDgeyu -a{eu'uIue1'zzlon4'deSossoueu1spwodu

'sIW'aaupn:aa$>gud'ea

'Sg'uenpueA''so:ou&ulo

aapoalo'8'J'o'spud

spJuuQG4'CIeU'SuqepJu1 's

.p:aQualo{alon3'd 'a:'analalosplouaagu

's&uSloS4tlouaaaaP6'o

'$o^'UUsppap7ulosloaaustu,#s^agsrS 'a

qso1usiro439'>'&a:aGppw

uslhaaUI'UuuPu0apueePaF1ogJo .

fr'a'duptapusaeUg6SouoJU'uo '

ef:t4o)uoprp&'ygalSN