From Violin to Piano A Perspective on Beethoven's ...

Transcript of From Violin to Piano A Perspective on Beethoven's ...

!

Oksana Germain

61807215

From Violin to Piano: A Perspective on Beethoven’s Arrangement of his

Violin Concerto Op. 61

Masterarbeit

zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades

Master of Arts

des Studiums Masterstudium; Klavier (HS-QSG)

Studienkennzahl: RA 066 711

an der

Anton Bruckner Privatuniversität

Betreut durch: Caroline Stahrenberg

Zweitleser: Michael Korstick

San Diego, CA, USA

September 5, 2020

ANTON BRUCKNER PRIVATUNIVERSITÄT für Musik, Schauspiel und Tanz Hagenstraße 57 I 4040 Linz, Österreich I W www.bruckneruni.at

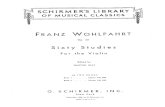

Abstract

The piano arrangement of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto Op. 61 is a unique concerto in comparison with the Violin Concerto and Beethoven’s well-known five piano concertos. It was composed only the year after the Violin Concerto, at the request of Muzio Clementi who wanted publishing rights to Beethoven’s compositions. Arranging of original compositions for other instruments was not uncommon in the eighteenth century and the Violin Concerto, according to some critics, was so well received that it was supposed pianists would want to play it themselves. While the piano arrangement is different from the five piano concertos of Beethoven, it is also similar in many ways. The Violin Concerto is more idiomatic for the instrument than its arrangement is for the piano due to obvious changes in texture between the two instruments which affects balance, technical difficulty, and other such aspects. In spite of the fact that this piano concerto may not be at the same level as Beethoven’s famous five piano concertos, it still has its charm and is one concerto which I hadn’t heard of previously and which I wouldn’t mind performing with an orchestra in the future.

� of �1 49

Table of Contents

Introduction Page 3

Development and Historical Background

A Biographical Context Page 4

Genesis of the Two Works Page 7

18th Century Composers and Arranging Page 12

Beethoven’s Violin Concerto and Others of the Time Period Page 14

The Authorship Dispute Page 16

Analysis and Performance

A Brief Analysis Page 19

Performance Practice and Joseph Joachim Page 22

Differences Between the Two Concertos Page 24

The Piano Arrangement: Performance Challenges Page 26

Period Performance: Pianos of the Era Page 36

Conclusion Page 42

Sources Page 46

Bibliography Page 47

Statutory Declaration Page 50

� of �2 49

Introduction

In my thesis, I will discuss Beethoven’s Violin Concerto Op. 61 and his arrangement of it for the piano. Firstly, to provide context for the genesis of both the violin concerto and its piano arrangement, I will provide a few details about Beethoven’s life and which events took place around the time in which he composed these two works. I will then provide brief analyses of both the violin concerto and it’s piano arrangement, then comment on any changes made during the composition of the piano version. This will lead to a perspective on whether or not the writing in both works was idiomatic for their respective instruments. In order to determine any idiomatic aspects of the piano arrangement, I will explore what some challenges might be in arranging this particular piece for the piano. In addition, performance practice will be an important element, including which instruments were used in Beethoven’s time. Just three years prior to the composition of the Violin Concerto, Beethoven had received an Erard piano which he could have used for the piano arrangement. Other 1

possibilities include Stein or Streicher pianos, one or both of which he is assumed to have obtained a few years earlier. It is believed, however, that Beethoven used a 2

Streicher for the piano arrangement because of the six and a half octave range which he used for the first time in this composition. 3

Before starting to write this thesis, I researched and read many different articles on various aspects of my topic searching multiple platforms on the internet. Unfortunately, I was not able to go to a music library or to the school library as, because of the situation with the pandemic, I had to suddenly leave school and go home and my city was in lockdown for some time. I had limited resources on the internet because, although some websites included large lists of pertinent source names, I was not able to find a lot of the articles in full. I ended up mainly using JSTOR and was able to find a few pdfs online of some shorter books about Beethoven’s Violin

William S. Newman. “Beethoven’s Pianos versus His Piano Ideals.” Journal of the American 1

Musicological Society, vol. 23, no. 3, 1970, p. 488 William S. Newman. “Beethoven’s Pianos versus His Piano Ideals.” Journal of the American 2

Musicological Society, vol. 23, no. 3, 1970, p. 484 Newman. “Beethoven’s Pianos versus His Piano Ideals.” 1970, p. 4923

� of �3 49

Concerto. When I started writing my paper, as I wrapped up my research I was given the opportunity to interview two wonderful violinists who have had experience practicing and performing Beethoven’s Violin Concerto so that I could get a perspective from them on the violin portion. I would like to thank Sergei Galperin and Annelle Gregory for offering to answer my detailed questions about their view of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto and how they would approach it. In conclusion, I will provide some perspective and context of where these two works fit into the body of their respective repertoires. Being that the piano concerto is a lesser known piece, I would like to show how it compares to Beethoven’s other concerti. Put into historical context and with the added information of Beethoven’s compositional output and inspiration at the time, this thesis will give a perspective on where these pieces fit into the repertoire of each instrument. In the end, I would like to see whether or not the piano arrangement of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto Op. 61 is idiomatic for the instrument, compared to his other piano concertos.

Development and Historical Background

A Biographical Context

1806, the year in which Ludwig van Beethoven composed his Violin Concerto Op. 61, was an important and eventful year for many reasons. The most significant event of the year could have possibly been the birth of Beethoven's nephew Karl on September 4, 1806 to his brother Kaspar Anton Karl van Beethoven and wife Johanna Theresia Reiss, who had just been married three months prior to their son’s birth. 4

Another more momentous occasion, in May of 1806, was that of Beethoven’s betrothal to his former student in Vienna, Theresa von Brunswick, the sister of his friend Count Franz. The result of this happy occasion for Beethoven brought about the composition of the Fourth Symphony Op. 60 which he wrote entirely in one sitting, after dropping

Donald W. MacArdle. “The Family van Beethoven.” The Musical Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 4, 1949, 4

p. 538.

� of �4 49

the C minor Symphony in the middle of composition. Having been commissioned by 5

Count Andreas Razumovsky the previous year to compose his Three String Quartets Op. 59, he completed them in 1806 before having them published in 1808. Another major composition completed in 1806 was the Thirty-two Variations for Piano WoO 80, which was published the following year in 1807. 1806 also saw performances of the second version of Beethoven’s Fidelio, also known as Beethoven’s preferred title, Leonore. 6

1807 was a bit busier for Beethoven as he was actively composing intensive works and having them published. Both Prince Nikolaus Esterhazy and Muzio Clementi, who met Beethoven for the first time that year, commissioned works, the former requesting a mass - Mass in C Op. 86, and the latter three piano sonatas - Op. 78, 79, and 81a. Upon meeting Clementi, Beethoven requested the publishing of his String Quartets op. 59, Fourth Symphony, and other works, a request which was accepted. Beethoven also submitted a petition to the Court Theater in Vienna for a position as composer but was not successful. During this time, Beethoven worked on his Fifth Symphony, Coriolan Overture op. 62, Cello Sonata op. 69, and Mass in C op. 86. 7

Leading up to the composition of the Violin Concerto Op. 61, notable works include the Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Op. 55, the Triple Concerto in C Op. 56, Piano Sonata No. 23 in f Op. 57, and the first version of Fidelio Op. 72. Other compositions completed in 1806 include his Piano Concerto No. 4 in G Op. 58, Symphony No. 4 in B-flat Op. 60, String Quartets Op. 59, Thirty-two variations on an original theme in c WoO 80, and an overture along with the second version of Fidelio. The same year that Beethoven arranged the Violin Concerto for piano, he also composed his Symphony No. 5 in C minor Op. 67, Cello Sonata No. 3 in A Op. 69, Coriolan Overture in c Op. 62, another overture for Fidelio and a mass. The first ever violin concerto Beethoven wrote,

Romain Rolland. Beethoven. Chapter 1: “His Life”. Gutenberg. November 12, 2017. Original 5

published in 1903. Stanley Glenn. “Some thoughts on biography and a chronology of Beethoven's life and 6

music.” The Cambridge Companion to Beethoven. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 10. Stanley Glenn. “Some thoughts on biography and a chronology of Beethoven's life and 7

music.” The Cambridge Companion to Beethoven. p. 10.

� of �5 49

WoO 5, helped to set the stage for the later concerto Op. 61. Unfortunately, this concerto was never finished. Other compositions directly leading up to the writing of the violin concerto op. 61 are two Romances Op. 50 in F (1798) and Op. 40 in G (1801-2), and the ‘Kreutzer’ sonata Op. 47 (1802-03). Out of these compositions 8

around the time Beethoven composed his piano arrangement, his Piano Sonata Op. 57 is a good example which offers similarities to the piano arrangement in texture and spacing of the hands which are two octaves apart in both works. They also are alike in lightness of texture at some parts of the scores as well as similar in the motion of the hands. At the same time as Beethoven received piano lessons from his father, he was also coached on the violin. Later, he was tutored on both the violin and viola by Franz Georg Rovantini who was a distant family member of Beethoven’s and a young violinist in the court. Ludwig’s instruction in the stringed instruments ended suddenly at the death of Rovantini in 1781. Beethoven had, however, always loved the violin and 9

attempted to keep up his playing but was, unfortunately for him, never able to succeed. A major reason for this could have been his poor hearing, an ailment which generally makes it difficult to attain good intonation and sound on a stringed instrument like the violin. Later in life, he took a few lessons with Franz Ries, Wenzel Krumpholz, 10

and Ignaz Schuppanzigh, even playing his own violin sonatas with student Ferdinand Ries accompanying on the piano. However, while Beethoven was an excellent pianist, even before he lost his hearing, his intonation left something to be desired. 11

Fortunately, his love for the instrument led him to compose the famous Violin Concerto Op. 61 which is learned and performed by most Classical violinists at some point during their careers. 12

Robin Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. Cambridge Music Handbooks. Cambridge 8

University Press, New York 1998. p. 4. Robin Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. 1998. p. 3.9

Lawrence Sommers. “Beethoven’s Violin Concerto.” Music & Letters, vol. 15, no. 1. 1934, p. 10

46. Robin Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. 1998. p. 3.11

Lawrence Sommers. “Beethoven’s Violin Concerto.” Music & Letters, vol. 15, no. 1. p. 46.12

� of �6 49

Genesis of the Two Works

The idea to compose this concerto came to Beethoven when he observed Viennese violinist Franz Clement in performance and liked his style and ability. He had 13

first met this young prodigy in Bonn at a concert which was part of his performance tour. Clement also went to London in the same year, 1791, and appeared with Haydn there. In a letter to Clement himself, Beethoven said: 14

“Go forth on the way which you hitherto have travelled so beautifully, so magnificently. Nature and art vie with each other in making you a great artist. Follow both and, never fear, you will reach the great-the greatest-goal possible to an artist here on earth. All wishes for your happiness, dear youth; and return soon, that I may again hear your dear, magnificent playing.” 15

Although Beethoven may have had nothing but high praise for Clement early in the violinist’s career, in 1819 after a concert in which Clement performed a work Beethoven composed of variations on a theme, the latter wrote poorly of him in his conversation-notebooks, seeming to demonstrate that Clement’s abilities and talents had subsided or diminished in some shape or form, saying the following concerning Clement’s composition: “Poor stuff, empty, quite ineffective…with great monotony he contrives fifteen or twenty variations, and ends each one with a fermata. You can imagine what one had to put up with! He has lost a great deal, and seems too old to be entertaining with his capers on the fiddle.” 16

Sommers. “Beethoven’s Violin Concerto.” p. 46.13

Duncan Druce. “A Viennese Violin Concerto.” Early Music, vol. 34, no. 2, 2006, p. 314.14

Robert Haas and Willis Wager. “The Viennese Violinist, Franz Clement.” The Musical 15

Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 1, 1948, p. 22.Inscription in an album of Clement’s written by Beethoven in Vienna in 1794. Quoted from: Robert Haas and Willis Wager. “The Viennese Violinist, Franz Clement.” The Musical Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 1, 1948, p. 22.

Robert Haas and Willis Wager. “The Viennese Violinist, Franz Clement.” The Musical 16

Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 1, p. 24.From the conversation-notebooks of Beethoven around or after the year 1819. Quoted from: Haas and Wager 1948, p. 24.

� of �7 49

For this reason, when Clement showed interest in being the concert-master for the performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, he was promptly rejected by the composer. 17

Clement is known as the musician who performed Beethoven’s works at a time when they weren’t yet so well received or accepted. Some compositions he was linked with are the Eroica, Christus am Ölberg, Ruins of Athens, and Overture to the Play “Hungary’s Benefactor”. He was born in 1780 in Vienna and first started taking violin lessons at the age of seven, after having been discovered as a virtuoso with immense talent to the extent that he was giving concerts at the age of eight years old. 18

It is said by some that Beethoven did not complete the composition of the concerto until the day of the performance, which forced Clement to have to sight-read the last movement, but a look at Beethoven’s manuscript makes that seem like an impossible story as, I can imagine, it isn’t very legible. The Wiener Theaterzeitung published a review of Clement’s performance of Beethoven’s violin concerto: “The excellent violinist Clement played, among other remarkable pieces, a violin concerto by Beethofen [sic] which, due to its originality and some very beautiful passages, earned exceptional applause. It was the art of Clement especially that was acclaimed for its charm, force, and surety of intonation. As for the concerto of Beethoven, the judgment of the critics is unanimous; certain beauty is conceded, but they find that the construction is weak, and that unending repetition of certain uninteresting places might easily cause fatigue.” 19

Clement reportedly added other “remarkable pieces” to the program as this would be the first time Beethoven’s new composition, the violin concerto, would be performed so he wasn’t sure how it would be received. The other pieces were safety measures of a sort, to ensure the success of the performance, even if the concerto wasn’t well received. These pieces included an overture by Méhul and a set of variations composed by Clement himself which he performed while holding the violin upside

Robert Haas and Willis Wager. “The Viennese Violinist, Franz Clement.” p. 25.17

Haas and Wager. “The Viennese Violinist, Franz Clement.” p. 15.18

Lawrence Sommers. “Beethoven’s Violin Concerto.” p. 47.19

Wiener Theaterzeitung publication. Year Unknown. Quoted from Lawrence Sommers. “Beethoven’s Violin Concerto.” Music & Letters, vol. 15, no. 1. 1934, p. 47.

� of �8 49

down. Another review by the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung released in January 1807 stated, “Admirers of Beethoven will learn with pleasure that he has composed a violin concerto, which the favorite Viennese violinist Clement executed with his habitual elegance and clarity.” 20

Johannn Nepomuk Möser wrote: “[…]With regard to Beethhofen’s [sic] concerto, the opinion of all connoisseurs is the same; while they acknowledge that it contains some fine things, they agree that the continuity often seems to be completely disrupted, and that the endless repetitions of a few commonplace passages could easily lead to weariness. It is being said that Beethohofen [sic] ought to make better use of his admittedly great talents, and give us works like his first Symphonies in C and D, his charming Septet in Eb, the spirited Quintet in D and others of his earlier compositions, which will assure him of a permanent place among the foremost composers. It is feared, though, that if Beethhofen [sic] continues to follow his present course, it will go ill both with him and the public. The music could soon fail to please anyone not completely familiar with the rules and difficulties of the art. Burdened by a host of unconnected and piled-up ideas, and a continual tumult of different instruments which should merely create a characteristic effect at their entry, he could only leave the concert with an unpleasant sense of exhaustion. The audience in general were extremely pleased by this Concerto and by Klement’s [sic] improvising.” 21

The editor of the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, Friedrich Rochlitz described the overall reception of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto by using the phrases “awed, but sceptical”, “generally reflecting ‘neither condemnation nor outright acceptance’”. 22

Lawrence Sommers. “Beethoven’s Violin Concerto.” p. 47.20

Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung publication in 1807. Quoted from Sommers “Beethoven’s Violin Concerto.” 1934, p. 47.

Robin Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. 1998. p. 32.21

Quoted from Robin Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. Cambridge Music Handbooks. Cambridge University Press, New York 1998. p. 32.

Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. 1998. p. 35.22

Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung publication in 1841. Quoted from Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. 1998. p. 35.

� of �9 49

Eight years later, after having heard the Violin Concerto performed numerous times, the same newspaper took a different stance on the concerto: “Most interesting is the Violin Concerto in D major, the only known from or written by Beethoven. We have heard it frequently over several years in Leipzig and always with enjoyment. In outline, it follows the customary concerto form and is so interesting as a composition, as well as so gratifying to the player as a solo piece, that we must express our astonishment that it is not chosen more often by tasteful violin virtuosos for the public domain. Moreover, the two additional cadenzas give the player splendid opportunity to shine not only as a virtuoso but also as a skillful artist. Mr. Jerome Gulomy, whose acquaintance we have made for the first time in this concerto, performed it very beautifully, intelligently and tenderly and with an artistic unanimity, which is peculiar only to genuine talent and a truly educated artistic mind.” 23

As is shown by the varying commentary and critique, the concerto wasn’t so well received at it’s premiere but, as it was performed more the public came to understand and even to appreciate it. Following Clement’s premiere of the concerto, the next performance in 1816 by a Viennese amateur of the first movement did not go so well, which led to violinists avoiding the piece until it was performed again by Baillot in 1828 at a Beethoven gala 24

in Paris. This time, it was so well received that the performance was repeated a few months later by the same artist, after which the work was premiered in London by fourteen year old Henri Vieuxtemps in 1832 and thirteen year old Joseph Joachim in 1844. Joachim, upon adopting the concerto, set out to perform it again under Robert 25

Schumann in Berlin in 1852, and Düsseldorf in 1853. He and Moser, Joachim’s biographer and pupil, created the three-volume Violinschule, in which Joachim included his own edition of Beethoven’s concerto for violin. He set his own ideas for 26

fingering and bowing as well as composed three sets of cadenzas for this violin

Robin Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. 1998. p. 35.23

Haas and Wager. “The Viennese Violinist, Franz Clement.” p. 16.24

Sommers. “Beethoven’s Violin Concerto.” p. 48.25

Robin Stowell. “Beethoven’s Violin Concerto Op. 61 and Joseph Joachim: A Case Study in 26

Performance Practice.” Early Music Performer, no. 14, Oct. 2004, p. 4

� of �10 49

concerto in Beethoven’s style and set the precedent for the performance of this classic for all artists to come. Eugene Ysaye himself, upon hearing Joachim perform the 27

concerto in the mid 1880s said: “[He played it] so well that he now seems part of it. It was he[…]who showed it to the world as a masterpiece. Without his ideal interpretation the work might have been lost among those compositions which are placed on one side and forgotten. He revived it, transfigured it, increased its measure. It was a consecration, a sort of Bayreuth on a reduced scale, in which tradition was perpetuated and made beautiful and strong[…]Joachim’s interpretation was as a mirror in which the power of Beethoven was reflected.” (Joachim’s approach to Beethoven’s Violin Concerto will 28

be discussed in greater depth in Chapter 2.)Eduard Hanslick, a German Bohemian historian and music critic compared the performances of Joachim and Vieuxtemps: “At the close of the first movement it must have been clear to everyone that this was not merely an astonishing virtuoso, but an eminent and striking personality. Joachim, with all his bravura, is so completely lost in the musical ideal, that one might almost describe him as having passed through the most brilliant virtuosity to perfect musicianship. His playing is great, noble, and free…The Beethoven Concerto, especially the free, deeply emotional performance of the adagio (which almost sounded like an improvisation), proved the most decided independence of interpretation. Under Vieuxtemps’ bow the concerto sounded more brilliant and lively; Joachim’s interpretation was deeper, and surpassed, with truly ethical power, the effect which Vieuxtemps obtained by reason of his temperament.” 29

Ysaye himself didn’t make an attempt at playing the concerto until his early thirties, yet brought his own individual style to it which was highly respected. 30

Sommers. “Beethoven’s Violin Concerto.” p. 49.27

Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. p. 37.28

Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. p. 37.29

Eduard Hanslick. 1861. Quoted from Stowell. Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. p. 37.30

� of �11 49

18th Century Composers and Arranging

In the eighteenth century, it was common for more successful works to be arranged for other instruments by the composer, the publisher, or an arranger approved by either the composer or publisher. Nineteenth century records include arrangements of Beethoven’s works either completed by the composer himself or by other musicians, in which case Beethoven supervised their work very carefully. He transcribed ballets, 31

German dances, ecossaises, marches, chamber music, concertos, symphonies, overtures, and vocal works for piano but it isn’t known to what extent or what exactly these compositions are. An example of one of Beethoven’s other arrangements for 32

piano can be seen in his letter to Hoffmeister on January 15, 1801: “And for the time being I am offering you the following compositions: a septet (about which I have already told you, and which could be arranged for the piano-forte also with a view to its wider distribution and to our greater profit) 20 ducats.” 33

As discussed later on in Chapter 1 in the sub-chapter “The Authorship Dispute”, Beethoven may not have arranged many works for piano but some of his arrangements may have been completed by one of his colleagues or students which he then sent to the publisher when requested. In the course of seven years, Beethoven made a transcription of the third movement of his Piano Concerto in C Minor, renaming it “Kleines Konzert”, in addition to turning his Grosse Fuge into a duet piano piece for four hands, which he arranged himself after the publishing company Artaria failed to create an arrangement acceptable for Beethoven. 34

Myron Schwager. “Some Observations on Beethoven as an Arranger.” The Musical Quarterly, 31

vol. 60, no. 1, 1974, p. 81. Schwager. “Some Observations on Beethoven as an Arranger.” 1974, p. 83.32

Schwager. “Some Observations on Beethoven as an Arranger.” p. 85.33

Letter from Beethoven to Hoffmeister on January 15, 1801. Quoted from Myron Schwager. “Some Observations on Beethoven as an Arranger.” The Musical Quarterly, vol. 60, no. 1, 1974, p. 85.

Schwager. “Some Observations on Beethoven as an Arranger.” p. 86.34

� of �12 49

Other recorded evidence of violin concertos being arranged for piano, besides Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, include a few violin concertos composed by Giovanni Battista Viotti, arranged for piano not by Viotti himself but by pianists Steibelt and Dussek. 35

After the premiere of the violin concerto in 1806, Muzio Clementi, who had long wished to obtain the English rights to Beethoven’s music, suggested in 1807 that he arrange the violin concerto for piano. In a letter to Collard, Clementi’s partner in London in April 22, 1807, he said: “I agreed with him to take in M.S. three Quartetts [sic] [Op. 59], A Symphony [Op. 60], an overture [Op. 62], a concerto for the violin which is beautiful, and which, at my request, he will adapt for the pianoforte with and without additional keys; and a concerto for the Pianoforte [Op. 58]…Remember that the Violin concerto he will adapt himself and send it as soon as he can.” 36

He then published it in London in 1810 with the following subscript, “This Concerto is adapted for the Piano-Forte, by the Author”. The piano arrangement score is titled Concerto for the Piano Forte…Composed by Lewis van Beethoven, Op. 61. The 37

arrangement was dedicated to Frau von Breuning and first published in 1808, after which the original violin score was published in 1809 and dedicated to Stefan von Breuning instead of Clement. 38

I was not able to find any evidence of the audience to which this piano arrangement was directed but I imagine there could be multiple reasons for its publishing. It’s highly possible that pianists in Beethoven’s time, upon hearing the violin concerto and wanting to play it for themselves, would have been extremely pleased at the publishing of the concerto as an arrangement for piano so that they could learn and play it for themselves. I have myself often heard compositions written for other instruments which I wished could have also been composed for piano and so I enjoy

Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. p. 48.35

Alan Tyson. “The Text of Beethoven's Op. 61.” Music & Letters, vol. 43, no. 2, 1962, p. 105.36

Letter from Clementi to Collard on April 22, 1807. Quoted from Alan Tyson. “The Text of Beethoven's Op. 61.” Music & Letters, vol. 43, no. 2, 1962, p. 105.

Alan Tyson. “Beethoven's Op 61.” The Musical Times, vol. 111, no. 1530, 1970, p. 827.37

Haas and Wager. “The Viennese Violinist, Franz Clement.” p. 16.38

� of �13 49

the transcriptions which other pianists make of some of those works. I believe this could have also been the case for pianists in the 19th century. Not only amateur or professional pianists but also those of intermediate level, or piano teachers, could have had access to the piano arrangement as a pedagogical source or just to play for enjoyment. Though I did not have the resources or enough time to find out just for whom this piano arrangement was meant, it would be an interesting topic for later research.

Beethoven’s Violin Concerto and Others of the Time Period

To give perspective to Beethoven’s violin concerto and the style of the time and looking at other works composed in the same period, only two other violin concertos were composed during the time these two works of Beethoven were completed. Franz Clement himself composed a violin concerto of his own in D major in 1805 which shows similarities with Beethoven’s style. The orchestration of both concertos is 39

similar, with the exception of some instrument omissions in the second movement of Beethoven’s concerto. The structure of tutti versus violin solo is also similar in the number of bars before the first entry of the soloist, with only a difference of 18 bars in Clement’s concerto. Beethoven also seems to have borrowed the contrasting major to minor method, which Clement himself incorporated into the second theme of his first movement. The last movement of both concertos are rondos in 6/8 meter and, the soloist enters with minimal accompaniment by the orchestra. This concerto premiered in the same concert as that of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony, in which Clement also participated. 40

The other violin concerto of this time period was that of Louis Spohr who finished his Violin Concerto No. 5, Op. 17 in 1807, the same year that Beethoven arranged his Violin Concerto Op. 61 for piano. Although there isn’t much information on Spohr’s violin concertos, after hearing a performance of Beethoven’s violin concerto by

Duncan Druce. “A Viennese Violin Concerto.” Early Music, vol. 34, no. 2, 2006, p. 314.39

Boris Schwarz. “Beethoven and the French Violin School.” The Musical Quarterly, vol. 44, no. 40

4, 1958, p. 442.

� of �14 49

Joseph Joachim with Mendelssohn conducting, Spohr is said to have commented, “This is all very nice, but now I’d like to hear you play a real violin piece.” Spohr is said to have not approved of Beethoven’s late works but it is reminiscent of the general feeling of the time, as violinists of that period were mainly interested only in performing their own works and not so much involved in learning or playing the compositions of other composers unless they were commissioned specifically for them with their style in mind at the time of composition. 41

Three other concertos were written in the period of 1806-1807 by lesser known composers Ferdinand Ries, Johann Baptist Cramer, and Joseph Wölfl. Ries was not only a full-time student of Beethovens since 1801, having three lessons a week with him, but was also supported by him both financially and otherwise, securing him a job as well. He also performed in various venues as Beethoven's student, playing his piano concertos for which he provided his own cadenzas. Ferdinand Ries composed his 42

Piano Concerto No. 6 in C Major, Op. 123 in 1806, the same year Beethoven completed his Violin Concerto Op. 61 and Piano Concerto No. 4 in G, Op. 58. The second piano concerto composed in 1806 was Joseph Wölfl’s Piano Concerto No. 5 “Grand Concerto Militaire”, Op. 43. Joseph Wölfl was a student of Leopold Mozart and Michael Haydn in his home-town of Salzburg and later dedicated a set of three piano sonatas to Beethoven. Wölfl and Beethoven were known to have piano duels to see who could improvise the best. 43

Johann Baptist Cramer composed his Piano Concerto No. 5, Op. 48 in 1807, the year Beethoven arranged his Violin Concerto for piano. Cramer was known for composing two books of studies Op. 50 for piano which were compared to Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words in that they were like poems. Beethoven himself highly approved these Studies as preparation for his own works and even assigned

Boris Schwarz. “Beethoven and the French Violin School.” The Musical Quarterly, vol. 44, no. 41

4, 1958, p. 442. Donald W. MacArdle. “Beethoven and Ferdinand Ries.” Music & Letters, vol. 46, no. 1, 1965, 42

pp. 23–34. Katalin Komlós. “After Mozart: The Viennese Piano Scene in the 1790s.” Studia 43

Musicologica, vol. 49, no. 1/2, 2008, p. 45.

� of �15 49

some of them to his nephew to practice. In a Musical Times article about J.B. Cramer, 44

the author states that a certain unknown man named Schindler says: ‘Our master (Beethoven) declared that these etudes were the chief basis of all genuine playing. If he ever carried out his own intention of writing a Pianoforte-School, these etudes would have formed in it the most important part of the practical examples.’” 45

The Authorship Dispute Sources dispute whether or not Beethoven truly arranged his Violin Concerto Op. 61 for piano and there is evidence to prove both views on this topic. Beethoven seemed to be active in the arrangement of his own compositions, yet hesitated to arrange other composers’ works but felt free to ask students or colleagues to arrange works of his own, though he was very picky about who he chose to arrange his compositions and how the process was completed. For example, Beethoven’s Fidelio 46

was arranged for piano by Ignaz Moscheles but Beethoven himself kept an eye on the process. Another example is a letter from Beethoven to Czerny which proves that the 47

latter was one of Beethoven’s arrangers: “My profound thanks for the affection which you have shown me. Unfortunately my brother forgot to ask you for the pianoforte arrangements for four hands of the overture. In this case too I trust you will comply with my request to undertake that as well. From the rapidity with which you have finished this pianoforte arrangement I see that it will give you no trouble to complete the other one also and as soon as possible. Unfortunately thanks to my brother the matter has been considerably delayed; so that everything must now be done at breakneck speed. I owe my brother a sum for which I

Frederick George Edwards. “J. B. Cramer (1771-1858).” The Musical Times and Singing 44

Class Circular, vol. 43, no. 716, 1902, p. 643. Edwards. “J. B. Cramer (1771-1858).” The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, vol. 43, 45

no. 716, 1902, p. 643.Quoted from Frederick George Edwards. “J. B. Cramer (1771-1858).” The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, vol. 43, no. 716, 1902, p. 643.

Schwager. “Some Observations on Beethoven as an Arranger.” p. 92.46

Schwager. “Some Observations on Beethoven as an Arranger.” p. 81.47

� of �16 49

have given him this overture and a few other works. That is the reason why he has been brought into his transaction. — By the way, please inform me what fee you ask for the two pianoforte arrangements. I shall be delighted to let you have it. A long time ago I informed you of my desire to be able to serve you. So if such an occasion should arise, please do not forget me. For I am ever ready to show you my affection, gratitude and respect. PS. Thinking that you may like to use the completed pianoforte arrangement when arranging the one for four hands, I have enclosed it.” 48

Beethoven even gave the publishing company Bernhard Schotts Söhne the opportunity the publish his arrangements with either his name on them or that of Czerny. 49

Questions have been raised as to whether or not Beethoven completed this arrangement himself. One reason for this being that he wasn't very interested in transcribing as a rule but the four cadenzas for the Violin Concerto apparently have Beethoven’s signature, which would seem to prove that he did arrange it himself. “Fritz Kaiser suggests that Beethoven’s contribution to the solo piano part was minimal, a plausible view in spite of the four cadenzas in the composer’s hand.” It seems as if 50

either Beethoven arranged the work for piano himself or at least did some major editing after having someone else, either one of his students such as Ries or Czerny, do the initial work. On the other hand, when Beethoven gave pianist Charles Neate a copy of the arrangement, he said that he himself had composed and played it. The authorship of the arrangement of this concerto is thus disputed by various Beethoven experts and theorists. 51

Tyson writes the following on his thoughts about the originality of the arrangement: “Anyone who wants to defend Beethoven’s full authorship should at any rate ask himself why there are no chords in the piano’s right hand — a form of abstinence

Schwager. “Some Observations on Beethoven as an Arranger.” p. 88.48

Letter from Beethoven to Czerny on October 8, 1824. Quoted from Schwager. “Some Observations on Beethoven as an Arranger.” 1974, p. 88.

Schwager. “Some Observations on Beethoven as an Arranger.” p. 89.49

Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. p. 48.50

Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. p. 4951

� of �17 49

renounced by the Beethoven who wrote the cadenzas. And he should look at the broken-backed adaptation of the coda of the first movement, particularly bars 511-23.” 52

The arrangement shows this in the left hand which has sparse and plain accompaniment patterns consisting mostly of broken triads and double the right hand part in octaves, unlike Beethoven’s usual style. At the time of this arrangement, Beethoven was also trying to finish another commission, the Mass in C, so this could be another piece of evidence that, because he was busy with the other commission and rushing to get the arrangement to Clementi, he could have given it to one of his students or colleagues to arrange in his place. In either case, Tyson and others are positive that, even if Beethoven didn’t arrange the work himself, he was supervising the process every step of the way and most probably edited the final draft before sending it to the publisher. 53

Robin Stowell, in his publication “Beethoven: Violin Concerto” was of the following opinion: “Pianists have almost completely neglected Op. 61a, largely because it is ‘highly unsatisfactory’ and because Beethoven’s five other piano concertos are in their various different ways so much more fulfilling. One wonders, however, whether it would be quite so maligned if listeners were not so familiar with the ‘original’ version for violin.” 54

I can understand how this could be the case as I myself had not known about this concerto and, upon hearing it, agree with Stowell that it can not compare to Beethoven’s five piano concertos. However, I would like to believe that Beethoven made this arrangement himself and just may not have spent much time on it due to the fact that he was asked to complete it in a short amount of time, in which he had already been spending his time working on larger compositions. If Beethoven hadn't been the one to arrange this concerto for piano, but had instead entrusted it to one of

Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. p. 4952

Tyson - Quoted from Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. 1998. p. 49. Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. p. 4953

Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. p. 4954

� of �18 49

his colleagues or students then this arrangement may not have been as interesting a topic. From Beethoven’s authorship of the arrangement, we can learn how he approached arranging in general as well as see what changes he made in the violin concerto to make it playable for the piano. Despite a few issues with balance and placement of the two hands in the piano score, discussed in chapter 2, this arrangement seems like it could be a good choice for piano students who are relatively new to Beethoven and piano concertos. This is because the level of difficulty of this concerto is similar to Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 2 and earlier Classical piano concertos which are very light in texture. This concerto is also good for technique building due to the running passages and practice in balancing of the two hands. Even though this concerto is not at the same level as Beethoven’s other piano concertos, I think it would still be a pleasure to perform with an orchestra.

Analysis and Performance

A Brief Analysis

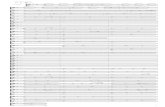

The following chart describes the structure of the first movement:

Bars

1-88 Ritornello 1 (Tutti exposition)1 D major/D minor

89-223 First solo (Solo exposition) D major - A major

224-283 Ritornello 2 (Development) [F major] A major/A minor - C major

284-364 Second solo C major - G minor

365-385 Ritornello 3 (Recapitulation) D major

386-496 Third solo

497-510 Ritornello 4

510 Solo cadenza (Solo cadenza)

511-535 Coda (Coda)

� of �19 49

From George Grove’s “Beethoven’s Violin Concerto. (Op. 61)”

Not unlike the first movement of a symphony, the first movement of this concerto is begun with a full-length tutti introduction before the violin solo makes its entrance. However, unlike a traditional symphony of the time period, Beethoven begins the concerto with an instrument which was normally used to create more noise and help the orchestra gain volume in the forte sections or higher: he makes an instrument made for accompaniment or added sound effect into that of a soloist. 55

The timpani begins the concerto with five even strokes, which resemble fate knocking, a motive which Beethoven is famous for using in some of his other compositions. According to Robert Stowell, Andreas Moser suggested a possible inspiration for this motive which seems to be a hypothesis and is not proven to be true: “The idea of this curious motive is said to have occurred to Beethoven during the stillness of a sleepless night, on hearing someone knocking at the door of a neighboring house. The knocking consisted always of five regular blows in succession, repeated after a pause; and Beethoven, overjoyed at being able to distinguish the sound so clearly, for at this time his hearing was beginning to be seriously impaired, used it as the opening theme for the violin concerto with which he was then occupied. Thus these sounds, so prosaic in themselves, became for him the germ of a musical idea, from which, in the course of the movement, he evolved a wonderfully poetic meaning.” 56

His Waldstein and Appassionata Sonatas, Fourth Piano Concerto, and Fifth Symphony also show repeated-note patterns. The only difference between the two was the motion behind it. In the Violin Concerto, a five-note motive begins the piece as a stabilizer of sorts, while the repeated-note pattern in the before-mentioned four compositions acts as a propeller of forward motion. 57

George Grove. “Beethoven's Violin Concerto. (Op. 61).” The Musical Times, vol. 46, no. 749, 55

1905, p. 459. Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. p. 61-6256

Andreas Moser - Quoted from Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. 1998. p. 61-62. Stowell. “Beethoven: Violin Concerto”. p. 6257

� of �20 49

Example 1: 58

Years before Beethoven was even born, Johann Sebastian Bach himself had the idea to open his ‘Christmas Oratorio’ in the same style, with a drum solo playing four repeated notes followed by the entrance of the wind instruments, as shown in the following example:

Example 2: 59

It is highly unlikely, however, that Beethoven had known this early work by Bach. Aside from this one rhythmic pattern found in Beethoven’s Concerto and Bach’s Oratorio, there are no other similarities. 60

After the twice-repeated pattern of drum solo and woodwind melodic entrance, first in the tonic key and then in the dominant key, Beethoven makes a sudden change to the piece while keeping it in the same style: he keeps the four-note pattern but this time, not only is it played by another instrument, the violin, but instead of a D, Beethoven introduces D sharps. 61

Beethoven. Violin Concerto, Opus 61. Edited by Leopold Auer. New York: Carl Fischer, 1917. 58

p. 1. J.S.Bach. Christmas Oratorio, Part 1: For the First Day of Christmas, BWV 248. 1734. p. 1.59

Grove. “Beethoven's Violin Concerto. (Op. 61).” The Musical Times. 1905, p. 459. 60

This wasn’t actually the first time that Bach used this motive as the first time it appeared was in his Tonet ihr Pauken.

George Grove. “Beethoven's Violin Concerto. (Op. 61).” The Musical Times, vol. 46, no. 749, 61

1905, p. 459.

� of �21 49

Performance Practice and Joseph Joachim

Joseph Joachim had a very high-quality, lyrical sound which fit well with the style of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto. He achieved this sound by keeping the upper portion of his right arm held against his body and his wrist at a high angle in relation to the violin and bow. His fingers were kept close together, positioned so that the fingertips lay on the frog of the bow. He was able to control dynamic differences and color changes by using rotary wrist motion and tensing of the fingers. Carl Flesch, a former pupil of Joachim’s, stated that this method, though it may have worked for Joachim, was not natural in the least and led to violin students having problems with their arms, and even, in the worst cases, crippling themselves. 62

In some passages of the concerto, Joachim preferred playing on the E string instead of the higher A string positions. The passage below is an example of one place which he would play on the E string:

Example 3: 63

Dessauer explains the reason for this method by saying that “in order that this passage may sound exactly as bright and harmonious as before in the lower position, many violinists, among them Joachim, play it entirely upon the E-string.” He goes on to say that, while Joachim uses a fingering which requires sliding from third to sixth position, a better approach might be the use of two-strings. 64

During that time, vibrato was not only used to make longer notes sound beautiful, but also in passages which were played more quickly. Joachim and Moser’s Violinschule does not promote ‘habitual use’ of vibrato, ‘especially in the wrong place’,

Robin Stowell. “Beethoven’s Violin Concerto Op. 61 and Joseph Joachim: A Case Study in 62

Performance Practice.” Early Music Performer, no. 14, Oct. 2004, p. 5. Ludwig van Beethoven. Concerto pour Violon et Piano. Edited by Edouard Nadaud and 63

Hubert Leonard. Paris: Costallat et Cie, 1910. p. 34. Stowell. “Beethoven’s Violin Concerto Op. 61 and Joseph Joachim: A Case Study in 64

Performance Practice.” 2004, p. 5.

� of �22 49

and teaches that students should see ‘the steady tone as the ruling on’. It also suggests using vibrato ‘only where the expression seems to demand it’. In the Violinschule, for the following example, it is recommended, in accordance with each stress of the German text, that the vibrato ‘must only occur, like a delicate breath, on the notes under which the syllables “früh” and “wie” are placed’. The resulting performance leaves a large quantity of notes without vibrato:

Example 4: 65

While Joachim created his vibrato mainly using finger technique, Fritz Kreisler, who recorded Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in 1926, used his entire arm in addition to his fingers and hand to create more of a constant vibrato throughout the piece, instead of only using it in sections. 66

Due to the fact that Beethoven had not written any cadenzas for his violin concerto, even though he had written four for his piano transcription, violinists and performing artists were obliged to compose their own cadenzas. The most-often played cadenzas for this concerto were composed by Joachim and Kreisler. Joachim himself wrote two sets of cadenzas, one of which is a definite challenge while the other is easier. The more difficult cadenza which Joachim composed for the first movement consists of seventy-six bars in the same style as the beginning of the movement. It follows the general format with the timpani motive and solo entry in the first section. The timpani motive then returns in the development with a con delicatezza marking in

Joseph Joachim/Andreas Moser, Violin School, Book 3. Translated by Alfred Moffat. Berlin: 65

N. Simrock, 1905. p. 6. Stowell. “Beethoven’s Violin Concerto Op. 61 and Joseph Joachim: A Case Study in 66

Performance Practice.” p. 6.

� of �23 49

the left hand with pizzicato articulation. The second theme comes in the form of the soloist’s accompaniment but in triplet rhythm. A good amount of the rest of the cadenza is in the style of the soloist’s entrance and following material. 67

Differences Between the Two Concertos

A solid portion of the piece feels like two accompaniment parts instead of solo and accompaniment - the piano and tutti parts sound similar because we are used to, as an audience, hearing the piano accompanying the violin solo in place of an orchestra when needed. Not only is the tutti exactly the same in both concertos, but in the piano arrangement Beethoven used the same basic structure as that of the tutti for the piano solo when he added the left hand. For example, he sometimes places left hand chords either in the same place as that of the orchestra accompaniment or in place of a rest between notes in the right hand to fill in empty spaces. In certain passages, the accompaniment is very plain and unoriginal, either following the contour of the melody in eighth notes or just copying the right hand completely. In slightly more rare moments, the left hand is more pianistic, most often following the right hand in sixteenth-note passages with the same material instead of leaving only the right hand alone or interrupting with a chord or two now and then. Another tactic Beethoven uses, which also makes the piano arrangement sound like an accompaniment at times, is putting moving lines from the tutti into the left hand while the right hand is playing a running passage in the opposite direction. Measure 184 is one example of this tactic:

Stowell. “Beethoven’s Violin Concerto Op. 61 and Joseph Joachim: A Case Study in 67

Performance Practice.” p. 6.

� of �24 49

Example 5: Violin 68

Example 6: Piano 69

As far as texture is concerned, when Beethoven composed the violin concerto, he often uses sparse instrumentation and places the violin in high registers at times to help with balance. This isn’t true for the entire concerto though, as some portions leave the violinist struggling to be heard over the orchestra if not for special adjustments by the conductor and fuller sound from the soloist. On the other hand, the relationship between orchestra and violin should be almost that of a chamber-music mindset. According to violinist Annelle Gregory, “The violinist needs to have exceptional bow control in order to be able to adjust to the orchestra’s dynamics and phrasing.” 70

Ludwig van Beethoven. Violin Concerto, Opus 61. Edited by Leopold Auer. New York: Carl 68

Fischer, 1917. p. 11. Ludwig van Beethoven. Ludwig van Beethovens Werke, Serie 9: Für Pianoforte und 69

Orchester, Nr. 73. Concerto für das Pianoforte, arrangiert nach dem Violin-Concerto Op. 61. Edited by Breitkopf and Härtel. Leipzig, 1862-90. p. 6.

Annelle Gregory, Violin. Interviewed on July 28, 2020 at 11pm.70

� of �25 49

From the very beginning, the piano rendition of the violin concerto sounds like it was meant for violin. The lack of accompaniment in the left hand as well as the difference in ranges between the two hands shows this, not only in the beginning but also throughout the rest of the piece. On the other hand, the violin version sounds very pianistic due to the almost constant technical passages and runs either in sixteenth notes or triplets. Because Beethoven was more a pianist than a violinist, this work is accordingly lacking at times in true violinistic style - the violin shines more with pieces which are mainly melodic and singing rather than those filled with running notes. The piano, on the other hand, doesn’t have the same capability for singing, so running passages are more suited for the instrument, whereas the violin’s best feature is its singing capability. Gregory verified this when she said, “The lack of long singing melodies such as one would find in most violin concerti leaves less room for expression and makes it exceptionally difficult to make it sound like something more than scales and arpeggios. Every note has to be perfect in intonation and tone. Only then can one begin to work on a convincing interpretation.” Violinist Sergei Galperin, 71

when interviewed, said that the scales, arpeggios, and broken thirds, which make up the majority of this piece are standard basic training for good violinists but he agrees with Gregory when he said, “Making music out of these seemingly simple notes requires taste and tremendous skill in tone, phrasing and style.” 72

The Piano Arrangement: Performance Challenges

It is important that pianists keep in mind the fact that, instead of only one solo line with orchestra, they now have an added hand, so they should accordingly create the appropriate balance between the two hands and the orchestra. Beethoven uses the left hand to fill in rests and pauses which come in the middle of the right hand passages. He also takes advantage of having the use of an additional hand in places like measure 111 which, in the violin concerto, is a simple set of four triplet patterns. In

Annelle Gregory, Violin. Interviewed on July 28, 2020. 71

Sergei Galperin, Violin. Interviewed on July 26, 2020 at 8:30pm.72

� of �26 49

the piano version, he changes three of the four triplet sets to sixteenth-notes and gives the first set to the left hand in the bass so the range of notes is wider, fuller, and gives the measure a more virtuosic and pianistic aura. In measure 102 of the first movement, the melody is two octaves higher than the left hand accompaniment and, if the pianist really wishes to get a singing sound in similarity with that of the violin as much as possible, this leads to problems with balance between the two hands. Since the left hand accompaniment placement on the piano keyboard is near the middle of the piano, the sound is naturally louder while the melody being at the higher end of the keyboard gives pianists a challenge to balance the naturally softer sound of the high end with the naturally louder sound of the middle register. Here the difficulty is to really hear the melody while playing the accompaniment softly. Fortunately, a restatement of the second theme in measure 422, which is in a similar situation, puts half of the phrase in octaves which helps with the balance of the two hands:

Example 7: 73

Example 8: 74

Ludwig van Beethoven. Ludwig van Beethovens Werke, Serie 9: Für Pianoforte und 73

Orchester, Nr. 73. Concerto für das Pianoforte, arrangiert nach dem Violin-Concerto Op. 61. Edited by Breitkopf and Härtel. Leipzig, 1862-90. p. 3.

Ludwig van Beethoven. Concerto für das Pianoforte, arrangiert nach dem Violin-Concerto 74

Op. 61. Edited by Breitkopf and Härtel. Leipzig, 1862-90. p. 14.

� of �27 49

The lack of material in the left hand accompaniment and thin texture in the right hand makes this piece much easier than Beethoven’s other piano concertos. However, this also proves difficult to play as the right hand line is more exposed, so the challenge is to make sure all notes are clear and evenly played because everything is heard. Also, timing is important, as it is different for the piano to have to make jumps over multiple octaves versus having to do it on the violin. As a result, it could be easy to lose the pulse. Some of the passages are also a bit awkward as the runs require certain fingers to spread apart in a not-so-comfortable position. Fingerings in some running passages can also be tricky to figure out sometimes because of the awkward positions. One example of a more significant change which Beethoven made in the piano score is one solo passage in the first section where the soloist is alone and brings the tutti back in with a trill. The last measure before the orchestra’s entrance in the violin score consists of triplets and the last triplet set spans one octave directly before the trill. In the piano arrangement, that same measure takes the previous sixteenth-note patterns and just turns them into downward-playing triplets, while the violin version takes the triplets in a gradual upward-stepping motion. Just a few measures later, Beethoven clearly has made the passage easier to execute in the piano arrangement than in the violin score. While both the original and the arrangement start the passage the same, the violin switches to octaves and tenths in addition to triplets while the piano only has triplets which are mirrored in both hands. Some parts of the passage are the same in both scores with the exception of the added left hand, however, what started as easier in the piano ends a bit more virtuosic with the right hand copying the violin solo notes and the left hand following with sixteenth notes of it’s own. Overall, I get the general feeling that the left hand acts as a filler to what the right hand is doing and doesn’t contribute anything really besides giving the extra hand something to do. It is sometimes absent during long runs, which makes it sound like the violin version. One passage on page 10 of the violin score has a more natural-flowing triplet line which travels up and down the space of two octaves while the piano uses the same two-octave range but, after playing four triplet patterns down the octave, jumps back up to the top of the sequence multiple times, instead of using the more natural approach of the violin:

� of �28 49

Example 9: 75

Example 10: 76

Another instance is a triplet passage with turns in the violin part which is changed to sixteenth notes in the piano version. The harmonies are usually the same or similar in the piano version to that of the violin score but there are a few places in which, because of the repositioning of the accompaniment from the orchestra to the left hand, makes it sound like a tritone since the notes are close together. The end effect is a bit strange to my ears. One passage I find even stranger and not so comfortable to execute is found on page 13 (measure 413) of the piano score. When arranging the piano version of the

Ludwig van Beethoven. Violin Concerto, Opus 61. Edited by Leopold Auer. 1917. p. 17.75

Beethoven. Concerto für das Pianoforte, arrangiert nach dem Violin-Concerto Op. 61. Edited 76

by Breitkopf and Härtel. 1862-90. p. 10

� of �29 49

concerto, Beethoven, whether on purpose or inadvertently, made the execution harder for the piano than he did for the violin:

Example 11: 77

Example 12: 78

Beethoven could have left out the second sixteenth note, as it is written in the violin score, and kept the final eighth note before the jump, but he added the sixteenth note into the piano part and that makes execution both in technique and timing/rhythm a bit difficult. Being that the next few measures are for the soloist alone as a kind of small cadenza though, it can be dealt with. When asked how a violinist might approach this jump, Gregory answered: “I personally do a slight allargando in the 2nd measure so I can have enough time to make the shift without compromising too much rhythm. I’ve heard others play it

Beethoven. Concerto für das Pianoforte. Edited by Breitkopf and Härtel. 1862-90. p. 1377

Beethoven. Violin Concerto, Opus 61. Edited by Leopold Auer. 1917. p. 22.78

� of �30 49

that way also. If one wants to play it strictly in time, then you would need a slight break to make the shift.” 79

For the piano as well, especially with the added sixteenth note, it is only natural to take some time to arrive at the second note, though the added note, in appearance, doesn’t seem to ask for that approach. One particularly awkward moment in the piano score is not only awkward technically but also affects timing and rhythm. The left hand has a syncopated eighth-note pattern accompaniment to the right hand sixteenth notes in Measure 355 and this could prove tricky to coordinate the two hands at first.Another example of Beethoven changing passages according to the instrument’s capabilities is Measure 425 where the violin has triplets in octaves and tenths and he changed that pattern to triplets in half-step chromatics, thirds, and sixths for the piano as it is easier to execute. The octave passages in the violin which copy the melody in the orchestra sound more lyrical and melodic than the piano’s triplets so that is one section where the violin can shine more while the piano is made to be an accompaniment once more. The final statement of the theme in the first movement sees the two hands so close together to the point that one note is played by both hands at the same time. This seems unusual for Beethoven in this concerto as, in other instances, he has kept a decent distance between the two hands and this passage in Measure 521 is awkward both for technical reasons and balance. In these situations where balance can easily take a wrong turn, it is important to use very little pedal. On the other hand, some parts of the piano score, like in Measure 533 and 537, feature added notes in the left hand which don’t exist in any form in the violin part. While some piano arrangements of passages in the violin score may not be so pianistic, others are. One example is a passage in the violin score which include triplets over an octave span which was changed to being only sixteenth notes in the piano score. Both technical styles were written according to the instrument. Passages, like Measure 535, where both hands play the same running passages should be handled

Annelle Gregory, Violin. Interviewed on July 28, 2020 at 11pm.79

� of �31 49

with care, depending on the instrument playing the melody line, so as not to play over what should be heard the loudest (ie. measure 134). The finale in the piano version is very pianistic and like the style of Beethoven’s later periods - the right hand sixteenth-note runs added to the left hand make for a very dramatic ending. Beethoven is known for ending compositions with long passages which gradually build up to a climactic ending. The first movement of the Piano Concerto No. 4 ends with sixteenth and thirty-second-note runs gradually climbing the piano keyboard until the climax of two ending chords, which also appears in the violin concerto. The third movement achieves this with triplets in both hands. The first piano concerto ending, like the concerto itself in its entirety, is more in the style of earlier Classical compositions, finishing with a trill in the piano in the first movement and a small cadenza-like sequence in the third movement. The third piano concerto, on the other hand, starts to show more characteristics of the later Classical period, as the first movement ends with a sixteenth-note arpeggio run in both hands down the keyboard before making the final ascent in a scale to the end. The ending of the third movement is even more pianistic with octaves in both hands. While the first movement of the fifth concerto is less dramatic in terms of technical difficulty, the volume of three fortes makes up for it. The third movement makes up for the lack of drama in terms of technical difficulty by ending with sixteen-note scales and triplet runs.

The second movement, starting in measure 45, has a similar issue with the first movement regarding balance between the light melody and heavier accompaniment. This is because of the different registers on the keyboard. Accordingly, it is a challenge to balance lines so that the thin melody line is heard over the accompaniment. One place in the second movement which doesn’t really make sense is a passage where Beethoven added a turn in the piano part, which is non-existent in the violin score, when there already is so much material in the piano. The violin part doesn’t have a turn or an additional hand and it sounds much simpler that way. To me, it just seems that Beethoven added more notes, either to try and make it more interesting for the piano or just to have more material even though the balance is already much different than it

� of �32 49

would be with a violin soloist. The following section with the theme as melody may seem to some to have lost its beauty in the piano score because of the added left hand sixteenth notes which make it sound busy. The orchestral part of this section is simple and unassuming in this part without too many busy notes and the left hand in the piano adds, maybe excessive, amounts of material, changing the original aesthetic of the violin version. Of course, this piece was viewed differently in Beethoven’s time than it is now with modern instruments and sound so, if I were to take a trip back in time, it is a high possibility that I would have a different opinion. It is up to the listener to decide on their own view of the piece so I will leave it open for interpretation. One passage which was interesting in regards to different articulation was a measure where the violin score has a tenuto marking while the piano score shows a staccato with a slur. I think this is due to the different ways of articulation based on the instrument. On the violin, a tenuto would be accomplished with the bow, while, on the piano it would be done with a certain degree of finger action and the amount of time a key is held. Measure 69 is a good example of this. The end of the second movement also includes another awkward hand situation in Measure 73, being too close to each other and almost stepping on fingers to reach the same note. In the third movement, we see more copying of accompaniment in the left hand of the piano version but this time adding chromatic passing notes to the line in Measure 13. Another performance practice issue for pianists regarding large jumps in this piece is the following measure where the note right before the jump is the first note in the measure. So it could be tempting for the pianist, or just happen by accident, to place an accent on that note. This note should therefore be approached with care and as if it is the end of the phrase - in other words, to make it a resolution of sorts, an action which the violin would do naturally with the bow:

� of �33 49

Example 13: 80

Another interesting example of the difference in composition based on the abilities of the instrument is located on the same page as the previous example shown in Measure 52. In this measure, the sixteenth-note arpeggio action in the violin starts from above while that of the piano version starts from the bottom note. It is true that, for a pianist, having the moving line on the bottom with the static note on top is definitely technically less challenging and Gregory attests to the fact that the opposite way of playing this passage, the way it was written for the violin, is technically easier for the violin. She stated that, “[This way of executing this passage] is easier in this case because the bottom note is an open string. If it wasn’t, then this passage would be extremely difficult.” 81

Example 14: 82

Beethoven. Concerto für das Pianoforte. Edited by Breitkopf and Härtel. 1862-90. p. 23.80

Annelle Gregory, Violin. Interview. July 28, 2020 at 11:00pm.81

Beethoven. Violin Concerto, Opus 61. Edited by Leopold Auer. 1917. p. 33.82

� of �34 49

Example 15: 83

Yet another technical difference between both scores in the same page is where the violin has moving notes on top of a static bass but the piano has it in more of an octave format with both fingers moving in the same direction. This is due to the fact that the piano can’t easily reach some notes in the violin score which jump to a tenth or higher and are easier to navigate on the violin. In the piano version, this passage starting in Measure 68 proves to be one of the more technically difficult and pianistic places which is repeated twice. One aspect of this composition which appears in both scores is that of repetition, as shown in Measure 89. Beethoven tends to keep certain parts of the composition the same way it was started, without changing texture or rhythm. For example, in one measure of the piano arrangement, instead of keeping the violin chromatic line, he starts the passage with triplet arpeggios which are kept the same until the end of the phrase. I personally find that his approach to this concerto made it less interesting than it could have been. Overall, the original violin score, for me, is more interesting than the piano arrangement. It didn’t seem like Beethoven put a lot of time or effort into the arrangement, as he was asked to do it quickly, so I think that explains why it is so different from his original piano concertos. Even though the piano arrangement does have running passages and a few slightly more technically challenging parts, it is nothing like the five piano concertos or the violin concerto which are all more soloistic and expressive. The lack of left hand material, which is truer to the violin score, is not

Beethoven. Concerto für das Pianoforte. Edited by Breitkopf and Härtel. 1862-90. p. 23.83

� of �35 49

very pianistic for a concerto as well as the repeated passages which remain unchanged throughout, unlike those of the violin solo. Where sixteenth notes turn into an octave pattern in the violin part, Beethoven puts single syncopated notes in both hands of the piano score which doesn’t make sense for a piano which has the capacity to play a wider variety of notes. A few parts do prove more interesting than the violin score as the two hands in the piano create a call and answer pattern but, in general, the violin part could be seen as significantly more aesthetically pleasant to the ear than that of the piano. The piano arrangement mostly sounds like an accompaniment as it tends to copy the orchestral part except sometimes in different rhythmic forms like sixteenth notes instead of eighth-note triplets.

Period Performance: Pianos of the Era

To properly understand the arrangement of Beethoven’s violin concerto for the piano, it is important to know what pianos were being used at the time and particularly which piano was used in the composition of the arrangement. This is in order to better understand the concerto because of the differences in tone, range, and quality between pianos of Beethoven’s period and pianos of today. If we can understand the pianos of the eighteenth century, then we will better be able to interpret Beethoven’s works and understand a little bit better how he might have wanted his compositions played, using that knowledge to recreate his ideas on modern pianos as much as possible. Streicher, in a booklet he wrote in 1801, Kurze Bemerkungen uber das Spielen, Stimmen und Erhalten der Fortepiano , as a sort of owners’ manual given to everyone 84

who bought one of Nannette Streicher’s pianos, described the fortepiano of the time when he said: “Even though some people believe that it [the piano] must be far inferior to other instruments regarding expressive playing: such an accusation refers only to

Richard A. Fuller. “Andreas Streicher’s Notes on the Fortepiano: Chapter 2: ‘On Tone’.” Early 84

Music, vol. 12, no. 4, 1984, p. 462.

� of �36 49

fortepianos, which have an inflexible tone, an extremely heavy-to-play keyboard and an action which does not support the movement of the fingers[…]” 85

Streicher’s pianos were believed to have the lightest action in Vienna at the time while English and French pianos may have been heavier but their tone was fuller. 86

This booklet written by Streicher contains four chapters: the first chapter, titled ‘Viennese action’, discusses mechanics, tone production, tone quality, posture for body, arm, hands, and fingers, and proper relaxation, as well as discourages pianists from hard excessive playing. Chapter 3 and Chapter 4, ‘A tuning pin with proper string winding’ and ‘The instrument as a whole’, talk about suggestions for general maintenance, tuning, handling of piano and string replacement. Chapter 2, ‘On tone’, 87

talks about how to achieve one of the most important aspects of playing the piano - a beautiful tone. In this chapter, Streicher describes the tone of a fortepiano as dry, thin or meagre with a ‘silver tone’ which, if the pianist is not careful and plays too heavily, could easily become an ‘iron tone’. The fact that fortepianos of the time had dry 88

tones probably made playing fast sixteenth-note passages easier to make clean. Streicher gives an example of a true artist playing the fortepiano of the time in the correct way by describing the finger technique as “so light, solid, neat and so naturally beautiful” as well as the position of “the arms, the hand and the action of the fingers themselves is extremely quiet.” This example artist approaches a beautiful tone “because he seeks to play forte and fortissimo more through full-voiced harmonies than through individual notes” and uses a “quick efficient attack” instead of destroying the 89

keyboard trying to achieve the tone he desires. A true piano or pianissimo dynamic is important because “when light notes are produced with the utmost exactness and certainty, this and this alone affords the listener the greatest delight.” Even in that time 90

Tilman Skowroneck. “Beethoven’s Erard Piano: Its Influence on His Compositions and on 85

Viennese Fortepiano Building.” 2002, p. 526.Reflections of Streicher in his booklet. 1801. Quoted from Skowroneck.

Skowroneck. “Beethoven’s Erard Piano: Its Influence on His Compositions and on Viennese 86

Fortepiano Building.” 2002, p. 526. Richard A. Fuller. “Andreas Streicher’s Notes on the Fortepiano: Chapter 2: ‘On Tone’.” 1984, 87

p. 462. Fuller. “Andreas Streicher’s Notes on the Fortepiano: Chapter 2: ‘On Tone’.” 1984, p. 463.88

Fuller. “Andreas Streicher’s Notes on the Fortepiano: Chapter 2: ‘On Tone’.” 1984, p. 464.89

Fuller. “‘On Tone’.” 1984, p. 465.90

� of �37 49

period, it was recommended to make the melody clearer and louder than the accompaniment as they were used to hearing with strings and other solo instruments which had singing capabilities. He goes on to describe this desired way of playing in 91

regards to hand position and technique as well as pedaling. Addressing the reason “that the forte pianist overplays his tone more than other instrumentalists” , Streicher 92

says that, the same as the soundboards of string and wind instruments are closer to the ear than the keyboard, this is the reason pianists cannot control the tone the same way as the tone on the fortepiano of the time projected straight out and away from the pianist. The fortepiano didn’t have much vibration in the front so all the sound went to the back of it. For this reason, audience members standing towards the rear of the 93

piano could hear everything while, at the same time, the pianist would be thinking that the piano wasn’t producing any tone. This situation becomes worse in a large room as the sound takes more time to deflect off of the walls than in a smaller room. Streicher therefore recommends that the pianist use an “articulate, secure touch” which would be foolproof even for those with the most timid hands. A great way to experience and learn from the sound that the fortepiano made was to attend concerts in large halls and listen to and analyze how the sound was produced and what affect it made in the room. As for concerto performers, the fortepiano should be located closer to the audience than the orchestra. Violins should be positioned behind the piano with the bass and wind instruments further away. Before even beginning a piece, the pianist must wait until there is complete silence so that the first most important notes of the piece can be heard clearly. Accordingly, in a concerto the soloist should wait a half or entire beat longer than required before entering. This is all important commentary from Andreas Streicher for pianists on performance practice of the day which we can use even today to translate the style of the time to modern instruments. 94

The three pianos which Beethoven is most known for working with are held today in museums in Austria, Hungary, and Bonn. The Vienna Kunsthistorisches

Fuller. “‘On Tone’.” 1984, p. 465.91

Fuller. “On Tone’.” 1984, p. 468.92

Fuller. “‘On Tone’.” 1984, p. 468.93

Richard A. Fuller. “Andreas Streicher’s Notes on the Fortepiano: Chapter 2: ‘On Tone’.” 1984, 94

p. 469.

� of �38 49

Museum holds the French Erard piano, the Budapest National Museum has the English Broadwood piano, and the Bonn Beethovenhaus has his Austrian Graf piano. The first edition of the Harvard Dictionary of Music by Willi Apel describes Beethoven’s Broadwood piano: “A much heavier structure, allowing for a greater tension of the strings which thus become more sonorous; also the two pedals of the present pianoforte; an action, known as ‘English action’, which was much heavier than the Viennese action but also more expressive and dynamic. Small wonder that Beethoven much preferred his Broadwood to the Viennese instruments.” 95

Hanns Neupert talked about Beethoven’s change of pianos in his article “Klavier” which he wrote for Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart: “Beethoven went over to the English system after he acquired a Broadwood piano in 1818, and thanks to the growing predispisition to energetic playing, heavy tone production, and orchestral effects, this system eventually became universal, although the Vienna action still remained long in use in connection with such names as Ehrbar, Bösendorfer, etc.” 96

Beethoven was also in contact with the families of Stein and Streicher his whole life. His experiences with pianos were similar to Mozart’s in the beginning as, like Mozart, after using the Späth piano, he switched to the Stein piano and even went to see Johann Andreas Stein in Augsburg in 1787. Count von Waldstein himself may have given him a Stein piano in 1788. 97

In 1796, Beethoven wrote a letter to Johann Andreas Streicher showing his approval of Streicher’s piano which Beethoven himself had just received into his possession:

William S. Newman. “Beethoven’s Pianos versus His Piano Ideals.” Journal of the American 95