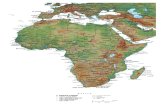

Boosting Organic Trade in Africa

Transcript of Boosting Organic Trade in Africa

Kenya 1

Boosting Organic Trade in AfricaMarket analysis and recommended strategic interventions to boost organic trade in and from Africa

COUNTRY MARKET BRIEF FOR KENYA

Imprint

Published by the

Deutsche Gesellschaft für

Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH

Registered offices

Bonn and Eschborn, Germany

Global project Knowledge Centre for

Organic Agriculture in Africa

Dag-Hammarskjöld-Weg 1-5

65760 Eschborn, Germany

T +49 61 96 79-0

F +49 61 96 79-11 15

I www.giz.de/en

As at

Bonn / Eschborn, 2020

Design

DIAMOND media GmbH

Neunkirchen-Seelscheid

Photo credits

istock/boezie, shutterstock.com

Text

ProFound Advisers in Development, Utrecht & Organics & Development, Markus Arbenz, Winterthur

Responsible: Dorith von Behaim, Eschborn

Referencing this report:

ProFound Advisers in Development, Organics & Development, Markus Arbenz (2020),

Boosting Organic Trade in Africa, IFOAM – Organics International, Bonn /

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Bonn / Eschborn.

GIZ is responsible for the content of this publication.

On behalf of the

German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ)

Division 124 – Rural Development, Land Rights, Forests

Dr. Maria Tekülve, Berlin

This Market brief series is based on a study com missioned by IFOAM – Organics International in 2020 in order to better understand possible interventions

that can promote market development and trade of organic produce in Africa.

The study was financed in the framework of the global project “Knowledge Centre for Organic Agriculture in Africa” (KCOA). The objective of the project is

to establish five knowledge hubs that promote organic agriculture in Africa by disseminating knowledge on the pro duction, processing and marketing of

organic pro ducts as well as shaping a continental network. The project is implemented by Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ)

GmbH on behalf of the German Ministry of Eco nomic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) as part of the special initiative ONE WORLD – No Hunger.

INTRODUCTION

The Kenya Market brief is part of a series with 12 specific Market briefs. They include information on the status of the organic sector and on the devel-opment of organic agricultural production and trade. They also provide deeper insight into how the organic market is organised: supply and demand dynamics including trends, supporting functions available and rules and regulations. All this is relevant information when trading with or in African organic markets.

The objective of the Market briefs is to inform national, regional and international specialists and interested public about the potentials of trade in organic products in and with African countries. The insights gained will facilitate the identification of possible interventions and opportunities and help to further build the organic sector in Africa.

This Market brief focuses on the organic market of Kenya. The complete series includes the following Market briefs:

1 Regional Market brief covering the 5 regions of the African continent: Southern, Eastern, Central, West and North Africa.

8 Country Market briefs covering the countries: Burkina Faso, Egypt, Kenya, Morocco, South Africa, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda

3 Product Market briefs covering the value chains: Coffee, Tropical fruits, Shea

Kenya 3

Fruit and vegetable market in Nairobi

4

4 Boosting Organic Trade in Africa

Overview and development

Kenya has a longstanding tradition in organic ag-riculture. The growth and development of the sector in Kenya was initially driven by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and institutes such as the Kenya Institute of Organic Farming (KIOF, formed back in 1986)1. From the mid-1990s, efforts shifted from fragmented and isolated approaches to more collaborative efforts. This resulted for instance in the establishment of the Kenya Organic Farmers As-sociation (KOFA), initiated by farmers participating in KIOF extension and training programmes. The association published organic farming standards for members based on the Basic Standard of IFOAM – Organics International and the European Union Organic Regulation.

KOFA wanted to develop an organic market, both locally and internationally, for their produce. How-ever, larger companies and commercial farmers were already united for the export market in the Kenya Organic Producers Association (KOPA). Eventually, all organic agriculture stakeholders, including KOFA and KOPA, united in the Kenyan Organic Agriculture Net-work (KOAN) as an umbrella organisation.

Official policies for organic agriculture or agro-ecology in Kenya do not exist yet, however public interest and recognition of organic agriculture has been increasing. There is limited integration of agro-ecology and biodiversity in agriculture in national policy documents as a crosscutting topic. The Minis-try of Agriculture has established an organic desk to lead the development of an organic policy under the department of Food Security and Early Warning Sys-tems together with KOAN and Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organisation (KALRO). This policy process began in 2009, and went through extensive sector analyses, draft policy development and consultation processes. As of 2020, a draft poli-cy is ready for deliberation by the Cabinet. Reasons for the duration of the process are seen in the lack of adequate empirical data to prove that organic farming is a sustainable and scalable production system, therefore leading to scepticism about its potential for volume production and subsequent demand in markets. In contrast, the Kenya National Agricultural Insurance Program launched in 2016 was rather unfavourable for the organic sector.

The current approach of the Ministry is to develop a policy for organic agriculture/agroecology within a broader context of policies concerning agriculture, food security and the environment. These are for in-stance the National Biodiversity Action Plan (NBSAP), policies related to Environment, Forests, and Bio-technology, the National Agriculture Investment Plan, and the Agricultural Sector Transformation and Growth Strategy 2019 – 2029. Organic agriculture has so far been incorporated in the Food Security Policy draft and the Soil Fertility Policy draft, with the latter having a focus on conservation agriculture.

A basic legal framework for seeds, crop production, environment, marketing, health and consumer pro-tection is in place. One way to get organic agriculture recognised as a mature sector at Kenya’s policy level, is the link with agroecology. In 2019, following a ‘Scaling up Agroecology’ call by the Food and Ag-riculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), a first conference was organised by the Biovision Africa Trust (BvAT), and the Kenyan Peasant League organised a first summer school on agroecology. This concept links well with international developmental priorities concerning the Sustainable Development Goals, the Aichi Biodiversity Targets and the Climate Change Action Plans, hence in line with the policy priorities of Kenya’s Ministry of Agriculture.

Another angle is food safety; many studies have showcased that produce at ‘wet markets’ and in supermarkets contain high levels of pesticide and heavy metal residues (see for example the Master Study of the Moi University in BvAT’s annual Eco-logical Organic Agriculture (EOA) report of 20182). In the same report, it is highlighted that Kirinyaga County has planned for a complete ‘organic city’. Similarly, Busia County supports the establishment of an organic fertiliser factory: private investors will build the factory, and the county provides land and funds to support the project. These cases exemplify the current conducive environment for developing organic agriculture in Kenya, and BvAT therefore continues with mainstreaming EOA into national policies as a key activity in Kenya.

1 Kundermann, B. and Arbenz, M. (2020). Agroecology – A Rapid Country Assessment.2 Biovision Africa Trust (2019). Ecological Organic Agriculture Project 2018, page 50.

5

3 Kundermann, B. and Arbenz, M. (2020). Agroecology – A Rapid Country Assessment.

Organic certified agriculture land:

154,488 ha (converted and under conversion)

Organic certified other areas (wild collection):

121,625 ha

Kenya’s organic production Infographic Kenya’s organic production

Percentage of Agriculture

0.56%Organic producers3:

in 2019: 44,966 certified producers + 22 processors and 32 exporters

The Rift Valley, one of Kenya’s most productive zones

Kenya 5

6

Products Area (ha) Volume (t) Export value(CIF in €)

Remarks

Apiculture a) 121,625 n/a. n/a.

Macadamia a) 50,516 a) 70,000 n/a.

Coconut a) 20,500 a) 50 n/a.

Cashew nuts a) 19,245 a) 20,000 n/a.

Fruit, including bananas a) 8,782 n/a. n/a.

Avocados a) 8,377 a) 5,789 n/a.

Fresh vegetables and melons a) 4,786 n/a. n/a.

Root crops a) 2,355 n/a. n/a.

MAPs (tea tree, herbs) a) 2,026 a) 502 n/a.

Sesame a) 715 a) 2,500 n/a.

Tea a) 583 a) 1,000 n/a.

Coffee a) 251 a) 5,000 n/a.

Moringa n/a. a) 50 n/a.

6 Boosting Organic Trade in Africa

List of main products (up to 20 products) that are produced:

■ Macadamia ■ Cashew nuts ■ Avocados ■ Coffee ■ Sesame ■ Tea ■ Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (MAPs)

(tea tree, herbs)

■ Coconut ■ Moringa ■ Apiculture ■ Tropical fruits ■ Fresh vegetables and melons ■ Root crops

List of certification bodies operational in Kenya:

■ Soil Association ■ Certification of Environment Standards (CERES) ■ Bioagricert (Bio Suisse standard in Switzerland) ■ AfriCert ■ EnCert ■ Nesvax Control ■ Ecocert ■ Institute for Marketecology (IMO) ■ Kiwa BCS Öko-Garantie ■ Uganda Organic Certification (UgoCert)

Data in above table are based on Research Institute of Organic Agriculture - FiBL (2018) statistics unless mentioned otherwise.

a) Research Institute of Organic Agriculture - FiBL (2018) statistics

Table: Products and production in Kenya

7

Kenya 7

Analysis

Agriculture is the backbone of Kenya’s economy, contributing 26 % of its gross domestic product, and 60 % of its export earnings4. Conventional horticulture and tea alone make up close to 30%. Approximately 80 % of the population lives in rural areas, with three quarters living below the poverty threshold. About 70 % of smallholder farmers are women. Overall, more than half of the population lives below the poverty line, and Kenya ranks among the ten most unequal countries in the world.

Four climate zones prevail in Kenya, where the Great Rift Valley in the southwest is the most pro-ductive. The eastern side of the valley is dominated by Mount Kenya, an extinct volcano, making the Eastern highlands one of the world’s richest ag-ricultural lands. Farms here were mainly established during the British white settler period and are large

compared to the rest of Kenya’s numerous subsis-tence farmers or nomadic pastoralists. They are pre-dominantly export-oriented with horticulture, fruits, coffee, tea and essential oils.

A large number of organic farms can be found here, connected to consumers in Nairobi and with good connectivity to international transport (airfreight terminal in Nairobi and commercial port in Mom-basa). Export markets dominate the organic trade picture and register dynamic growth because of increased demand. The local production sales pitch is based on self-claims (‘default organic’ or ‘natural’) or on Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS)5. Local markets are increasing but need more concerted efforts to reach scale beyond traditionally stronger export products and pioneer initiatives.

4 Kundermann, B. and Arbenz, M. (2020). Agroecology – A Rapid Country Assessment.5 Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) are locally focused quality assurance systems. They certify producers based on active participation of stakeholders and

are built on a foundation of trust, social networks and knowledge exchange. More information can be found here: www.ifoam.bio/pgs

Vegetable farmers harvesting

Main products for interregional export markets: Macadamia, coffee, tea, coconut

Main products for domestic and regional markets: Fruits, vegetables, moringa

Total volume of the exports: 4,846 tonnes in 2019 to EU & 66 tonnes in 2019 to USA

Total value of the exports: 24 million EUR in 2018 to EU, 423 thousand USD in 2019 to USA6

Number of operators that are exporting from Kenya: 32

Number of operators that are importing into Kenya: 15

Kenya’s organic market Infographic Kenya’s organic market

8

8 Boosting Organic Trade in Africa

Number of specialised/overall outlets in the domestic market: n/a

6 Data on export volume and value of organic produce from Africa is only available for the EU and the USA.

9

Kenya 9

Letters in the doughnut refer to:

a) Organic umbrellab) Certification,

Internal Control Systems & PGSc) Trade Facilitationd) Research and Advisee) Advocacy

f) Promotion & PRg) Export Standardsh) Private Standards & Regulationi) Promoting Policiesj) Trade Governance

a) KOAN and various organic institutions, Retail Trade As-sociation of Kenya (RETRAK) is both retail and organic consumer association

b) 8 Certification bodies (7 international + 1 local), 3 PGS schemes

c) 1 trade fair, some organic direc-tories and information systems, export promotion by KOAN, KIOF

e) Civil society with many non-governmental organisations, KALRO / KOAN as a reference

for organic policy, BvAT/EOA-I attracts in-terest through link to agroecology

f) Several donors and investors

g) Export market standards: European Union, U.S. National Organic Program, Naturland, Bio Suisse etc.

h) No organic regulation, East African Organic Products Standard (EAOAP), Kilimohai (not mandatory)

i) Organic policy in preparation for 10 years, no reference to “organic” in agriculture policy

j) No government support

ORGANIC TRADE

DEMAND SUPPLY

Informing andcommunicating

Setting and enforcing the rules

SUPPORTINGFUNCTIONS

RULES

Consumers, domestic outlets and importers

Farmers, cooperatives processors

d) Various national and international institutions doing research and development in organic agriculture, no organic extension

10

10 Boosting Organic Trade in Africa

Supply chains’ demand

Organic produce is visible to a very marginal extent. In informal local markets, it is often not possible to distinguish between conventional and organic. If said to be organic, it cannot always be verified and is sometimes referred to as ‘organic by default’ or ‘naturally produced’. In some way, through organic certification or PGS, standards need to be adhered to and controllable (traceability and transparency), otherwise there is a risk that producers following organic principles and practices may become discouraged.

Current consumer demand for ‘food-safe’ products can be a good driver for local organic markets, as well as for giving farmers a better return on their hard physical labour with fair prices. Even if it is difficult to find statistics, most respondents mention that there is a growing demand for organic products from Kenya. In Kenyan cities, consumers are increasingly worried about food safety issues (pesticide and heavy metal residues, microbiological contamination), and are therefore looking for better foods. Yet, the Kenyan retail sector is marked by strong competition and ‘boom and bust’ scenarios for supermarket retail chains. Because of the price competition with low margins, chances for organic suppliers are not good, but there are signs of specialist retailers (specialist outlets, restaurants and online delivery service) looking for oppor-tunities to cater to urban consumers who look for safe and responsibly sourced foods.

Supply chains’ supply

A large number of organic farms is concentrated in central Kenya, well-connected to consumers in Nairobi and with good connectivity to international transport. Organic production is organised around a small number of large farms, outgrowers and input suppliers. Fruits, nuts, coffee, essential oils, and tea are the five major organic product categories Kenya produces and exports. With respect to local markets, the above-mentioned trend of specialist retailers looking for opportunities to cater for con-scious consumers, offers opportunities for organic suppliers.

Market place

Kenya has a population of about 50 million. This in itself constitutes a large market potential for organic products, but over the years organic production has been geared to export markets. This is the result of low visibility of organic smallholder farmer’s efforts in producing for local markets; many of the pop-up ‘wet markets’ are irregular and informal; there are few semi-permanent outlets in shopping malls.

According to Kundermann and Arbenz (2020), the main local organic market is placed around the capital city, where a large number of consumers are foreigners and upper middle-class citizens. In Nairobi, the more than 10 outlets selling organic products are situated in the wealthy areas. The organic products sold in the supermarkets are typically coffee, tea, honey, sunflower oil, flour, macadamia nuts, and various health products. The greengrocers offer a variety of vegetables and fruits. Organic res-taurants and online delivery services exist in Nairobi and in Mombasa, with tourism being an important driver for organic food demand.

11

Kenya 11

Supporting functions

According to BvAT’s 2018 annual report, Kenya’s Ecological Organic Agriculture (EOA) national platform is fully operational, and the National Steering Committee (NSC) is keenly following the progress of EOA implementation at the country level. The NSC held 2 meetings in 2018, during which partner workplans, progress reports and exchanges were shared. The NSC has kept track of project implementation and provides advice and support, in particular with respect to creating synergies between implementing partners.

The Kenya Organic Agriculture Network (KOAN) is a national membership organ-isation for organic agriculture in Kenya, formed to coordinate, facilitate and provide leadership and professional services to all members and stakeholders in the organic sector in Kenya. Its members are farmers, traders, exporters, service providers (ex-tension officers, certification bodies), and research institutions.

As for international support, Busia County partnered with local organic NGOs to train its extension officers on organic agriculture through a donor-funded project, resulting in 18 extension workers attending the one-week training. The county’s ag-riculture office allocated the time for the extension staff to participate in the training.GIZ is active in mainstreaming biodiversity in agricultural landscapes, as a work-ing package in its global project “Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services in Agrarian Landscapes” funded by the German government. It also hosts policy dialogues and participates in forums as approaches to move from awareness to the development of guiding documents at national and county level. Together with organisations such as Bioversity International, GIZ supports the Busia Biodiversity Policy and influences the sector and extension policies on sustainable agriculture. In this context, the German Cooperation provides advisory services, financial services and support for agriculture research through its development bank KfW.

The Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) supports ecological or-ganic agriculture; the Swiss Biovision Foundation is active in organic and agroecolog-ical knowledge management and livelihood development. The Danish Cooperation supports agroecology and organic research as well as institution building.

Man selling mangoes and other fruits in a market stall in Mombasa

12

12 Boosting Organic Trade in Africa

Certification, ICS7 and PGS: There are various international certification bodies (CBs) involved in Kenya, including: Soil Association, Certification of Environ-ment Standards (CERES), Bioagricert (Bio Suisse standard in Switzerland), Af-riCert, EnCert, Nesvax Control, Ecocert, Institute for Marketecology (IMO), Kiwa BCS Öko-Garantie, Uganda Organic Certification (UgoCert).

Most of the CBs are international bodies using locally trained inspectors and certify in their offices overseas. A national certification body EnCert was established in 2005 to certify for the national markets. PGS exists in Kenya, but is not widespread. In May 2007, the East African Organic Products Standard (EAOPS) was launched after a consul-tative process, which started in 2005 by harmonising existing organic standards in the East African region. Together with the EAOPS, the ‘Kilimohai’ brand was developed to help promote and boost regional trade.

Building the capacity of ICS on PGS en-ables increased compliance with organic standards. The PGS may be managed by the private sector with endorsement/recognition by the government making it the common system for the country/region. An example for this is the East African Community (EAC) including Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Burundi and Rwanda. The East African Organic Products Standard is approved by the intergovernmental body of the EAC and linked to the regional East African Organic Mark, but the mark is managed by a consortium of the national organic umbrella organisations. This consortium also decides on the East African Organic Guarantee System, i.e. the Agroecology Rapid Assessment criteria for granting the use of the logo. Governments can adopt similar models whereby they del-egate the management of the common organic logo to the private sector.

Trade Facilitation Services: The Food Kenya trade show 2019 took place from 20 to 22 September at the Sarit Expo Centre, Nairobi. Food Kenya is the global platform that aims to connect international food and hospitality companies to showcase their products to the developing market of Kenya and other East and Central African countries. It will provide wider oppor-tunities for international and Kenyan companies to stand out with their distinctive products and explore the current requirements and opportunities in the market.

Advocacy, Research and Advise: Kenya has an active civil society. There are various organic and agroecology research and development institutions (International Center for Tropical Ag-riculture (CIAT), International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (Icipe), International Centre for Research in Agroforestry (ICRAF), Kenya In-stitute for Public Policy Research and Analysis (KIPPRA); Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organisation (KALRO), Biovision Africa Trust (BvAT), Participatory Ecological Land Use Man-agement (PELUM) Kenya, Sustainable Agriculture Community Development Programme (SACDEP), the Kenya In-stitute of Organic Farming (KIOF), the Organic Consumer Alliance, Consumer W@tch (by KOAN), and Organic Food Kenya. The Kenya Institute of Organic Farming (KIOF) is a non-governmental and not-for-profit organisation working throughout Kenya and the region of Eastern Africa in particular. Besides commercial purposes, it serves the public at large by promoting rural development and education in organic agriculture and related marketing ser-vices.

7 Internal Control Systems

13

Rules

Export Standards, Private Standards and Regulations: Kenya’s Agriculture and Food Authority is responsible for the production and trade of all agriculture pro-ducts. The authority is the successor of former regulatory institutions in the sector that were merged into directorates under the authority, including the Coffee Board of Kenya, the Kenya Sugar Board, the Tea Board of Kenya, the Coconut Devel-opment Authority, the Cotton Development Authority, the Sisal Board of Kenya, the Pyrethrum Board of Kenya, the Horticultural Crops Development Authority.

KOAN and KIOF have extension and training programmes. They published organic farming standards for members based on the Basic Standard of IFOAM-Organics International and the European Union Organic Regulation, the East African Organic Products Standard, and the East African Organic Mark.

Promoting Policies: Kenya has no national policy in place, but since 2009 it has been in the process of developing one. The following are initiatives and organisations that contribute to the policy development and the promotion of organic production and markets in Kenya. In addition to KOAN, KIOF and BvAT, media products such as spe-cialised radio shows and BvAT’s magazine “The organic farmer” are being produced. The Green Belt movement of Nobel prize awardee Wangari Maathai, AFSA (Africa Food Sovereignty Alliance) and international networks such as La Via Campesina with its member the Kenyan Peasants League closely liaise with the agroecological principles and movement in Kenya. The new Alliance of Networks in Agroecology in Kenya (ANAK) is being formed but does not yet have an internet presence.

Trade Governance: As mentioned above, Kenya’s Agriculture and Food Authority (AFA) is responsible for all production and trade of agriculture products.

Kenya 13

Smallholder potato farmer harvesting

14

14 Boosting Organic Trade in Africa

Conclusions

While Kenya used to have a strong and growing organic sector in terms of production and trade, this seems to have slowed down in recent years. Demand continues to be high, but a more con-ducive trade environment could leverage the growth potential. In this sense, it is interesting to compare to Ethiopia, which showcases how PGS as a local appropriate form of ‘certification’ has proven to be successful for organic producers and consumers. It is now a functioning certification scheme based on trust and registration by the Organic Desk of the Ethiopian Ministry of Agriculture. In Kenya, such an approach could help to reduce the relatively high cost of certification.

In its annual report on Ecological Organic Ag-riculture, BvAT points to the institutional challenges and limited enabling environment that hamper formal development of the organic sector. This is now being addressed by the Ecological Organic Agriculture Initiative (EOA-I), run since 2014 by the African Union Commission, BvAT, PELUM Kenya and other partners. They have designed a roadmap, a concept note and African Organic Action Plan to mainstream ecological organic agriculture into national agricultural production systems by 2025. This concept links well with international devel-opmental priorities concerning the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Aichi Biodiversity Targets and the Climate Change Action Plans, and is hence in line with policy priorities of Kenya’s Minis-try of Agriculture.

Another angle is food safety; numerous studies have showcased that produce at ‘wet markets’ and in supermarkets contain high levels of pesticide and heavy metal residues. The studies and the several cases demonstrate the need for safe food products

as well as BvAT’s continuing work of ‘Mainstreaming EOA into National Policies’ as a key activity. This exemplifies the current conducive environment for developing organic agriculture in Kenya.

Financed by the German government, GIZ im-plements a network of regional Knowledge Hubs for Organic Agriculture in Africa, with one hub being created in Eastern Africa. These can be instrumental to address the shortfall of available data in the organic sector in the region. Using the potential of organic agriculture requires in-depth understanding of ecological interrelationships and knowledge of practices in agricultural production, processing and marketing.

Furthermore, the private sector plays an important role in unlocking the potential of the organic sector, helped by consumers’ demand for safe and sound foods. The Retail Trade Association of Kenya (RE-TRAK), for instance, is the voice of the retail indus-try, its main objective being to put across retail trade concerns (e.g. with respect to safe and healthy food) to the different stakeholders.

Even though there are several trade fairs in Kenya, data is necessary concerning the results of such trade fairs, e.g. in the form of the values of the sales contracts established during the fairs. Fur-ther potential lies in the creation of functional trade platforms for the organic private sector such as the Kilimohai organic market place. Therefore, the par-ticipation of the private sector as a driver for devel-oping the organic sector is crucial. There is a strong rationale for inviting private companies to help set the stage for Kenya’s organic policy and priorities regarding products and markets, diversification and value addition/processing.

Square plots in the Rift Valley