EXTERNAL FEATURES OF THE DUSKY DOLPHIN Lagenorhynchus obscurus

Transcript of EXTERNAL FEATURES OF THE DUSKY DOLPHIN Lagenorhynchus obscurus

Estud. Oceanol. 12: 37-53 1993 ISSN CL 0O71-173X

EXTERNAL FEATURES OF THE DUSKY DOLPHINLagenorhynchus obscurus (GRAY, 1828) FROM PERUVIAN WATERS

CARACTERisTICAS EXTERNAS DEL DELFiN OSCUROLagenorhynchus obscurus (GRAY, 1828) DE AGUAS PERUANAS

Koen Van Waerebeek

Centro Peruano de Estudios Cetol6gicos (CEPEC),Asociaci6n de Ecologfa y Conservaci6n, Casilla 1536, Lima 18, Peru

ABSTRACT

Individual, sexual and developmental variation is quantified in the external morphology andcolouration of the dusky dolphin Lagenorhynchus obscurus from Peruvian coastal waters. Nosignificant difference in body length between sexes is found{p = 0.09) and, generally, little sexual

dimorphism is present. However, males have a more anteriorly positioned genital slit and anus andtheir dorsal fin is more curved, has a broader base and a greater surface area than females Althoughthe dorsal fin apparently serves as a secondary sexual character, the use of it for sexing free-rangingdusky dolphins is discouraged because of high overlap in values Relative growth in 25 body

measurements is characterized for both sexes by multiplicative regression equations. The colourationpattern of the dorsal fin, flank patch, thoracic field, flipper stripe and possibly (x2, p = 008) the eye

patch, are independent of maturity status. Flipper blaze and lower lip patch are less pigmented injuveniles than in adults No sexual dimorphism is found in the colour pattern The existence of adiscrete "Fitzroy" colour form can not be confirmed from available data. Various cases of anomalous,piebald pigmentation are described, probably equivalent to so-called partial albinism Adult duskydolphins from both SW Africa and New Zealand are 8-10 cm shorter than Peruvian specimens,supporting conclusions of separate populations from a recent skull variability study.

KEY WORDS: colouration, external morphology, dusky dolphin, population, Southeast Pacific.

RESUMEN

Se cuantifica la variaci6n individual, sexual y de desarrollo en la morfologia extern a y la coloraci6ndel delfin oscuro Lagenorhynchus obscurus de aQuas costeras peruanas No se detecta diferenciasignificativa en longitud corporal (p = 0,09) y, en general, poco dimorfismo sexual esta presente La

ranura genital y el ano se situ an mas anteriormente en log machos que en lag hembras Ademas, laaleta dorsal en log machos muestra una mayor inclinaci6n, tiene una base mas larga y una superficiemayor. Aunque, aparentemente, la aleta dorsal sirve como caracteristica sexual secundaria, no serecomienda usarlo para determinar el sexo de delfines oscuros en alIa mar por un alto nivel desobreposici6n en valores Ecuaciones de regresi6n multiplicativa caracterizan el crecimiento relativoen 25 medidas corporales, en ambos sexos EI patr6n de coloraci6n de la aleta dorsal, mancha delflanco, mancha toracica, banda de la aleta pectoral y, posiblemente (x2, p = 0,08), la mancha del ojo

son independientes del estado de madurez; la mancha pectoral y la mancha dellabio inferior en logjuveniles se yen menos pigmentadas que en log adultos. La existencia de una forma discreta decoloraci6n Ilamada "Fitzroy" no se puede confirmar con log datos presentes Se describe unaanomalia de la pigmentaci6n que probablemente es equivalente con albinismo parcial, conocido enotros mamfferos Los delfines oscuros adultos del suroeste de Africa y de Nueva Zelandia miden unos8-10 cm menos que log especfmenes del Peru, confirmandose conclusiones que forman poblacionesseparadas, basado en un estudio reciente de variabilidad cranial.

38 Estud. Oceanol. 12, 1993

INTRODUCTION

Particularities in the external features of whalesand dolphins can offer valuable insight in their gen-eral biology. Differences in colouration pattern, adultsize and body shape often indicate reproductiveisolation, and have contributed to the definition ofpopulations or management units of exploited spe-cies (e.g. YONEKURA et al., 1980; EVANS et al.,1982; BAIRD & STACEY, 1988; KASUYA et al.,1988; HEYNING & PERRIN, 1991; PERRIN, 1990;PERRIN et al., 1991). External features, such assexual dimorphism, play an important role in thevisual communication of gregarious cetaceans, andthey seem closely related to social interactions, es-pecially mating behaviour (see reviews by WURSIGet al., 1990; JEFFERSON, 1990). Ecological andbehavioural field studies are greatly enhanced if sexand some appreciation of age or maturity can bededuced for individuals from visible clues. It is there-fore rather surprising that the external morphologyand colouration for only a few small cetaceans havebeen studied in detail and with adequate samplesizes. All six species of the dolphin genusLagenorhynchus remain largely undocumented.

External measurements are available for onlyfour (sub)adult dusky dolphins Lagenorhynchusobscurus (GRAY, 1828; WATERHOUSE, 1838;LAHILLE, 1901; GALLARDO, 1912) and for oneneonate from New Zealand (ALLEN, 1977) andthese are of limited use, for it is unclear how theywere taken. WEBBER (1987) offered a body length-weight plot for 15 New Zealand dusky dolphins(mean adult length = 172.6 cm, range 166-184 cm)and compared colour patterns qualitatively betweenL. obscurus and L. obliquidens. Original observa-tions on the colouration of L. obscurus were pub-lished by GRAY (1828), WATERHOUSE (1838),LAHILLE (1901) and GALLARDO (1912); importantcomparative discussions are by KELLOGG (1941),BIERMAN & SLIJPER (1947, 1948) and FRASER(1966). MITCHELL (1970) in an excellent paperstandarized colour pattern components. Descrip-tions of colouration by GASKIN (1972), LEATHER-WOOD & REEVES (1983), and WEBBER andLEATHERWOOD (1990), presumably, were mostlyinspired by observations on New Zealand dolphins;those authors conducted much research in thatarea. DAWSON (1985) reported "considerable geo-graphic variation in colour pattern, and some patternvariation within local groups" in New Zealand. Amere three photographs of SE Pacific dusky dol-phins have been published (BINI, 1951; ANDRADE& BAEZ, 1980; GUERRA et al., 1987) without anydiscussion.

In New Zealand and Argentina, sex (and identity)of free-ranging dusky dolphins have been deter-mined through live-capture and photo-identificationbased on distinctive scars and nicks of the dorsal finand unusual pigment patterns (WORSIG & WOR-SIG, 1978; WORSIG & JEFFERSON, 1990). Cap-ture however is exceedingly unpractical while photo-identification permitted researchers to recognizeonly 20%, or less, of individuals. Some visual markerof sex and maturity that would permit real-time clas-sification of specimens would obviously be muchwelcomed.

Recently, large numbers of fresh dusky dolphinshave become available for study in Peru as a resultof high catch levels in coastal small-scale fisheries(READ et al., 1988; VAN WAEREBEEK & REYES,1990, in press). In the present paper I quantify anddiscuss the variation in external morphology andcolouration in Peruvian L. obscurus and offer apreliminary comparison with animals from other ar-eas.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Field procedures

Most of the information presented herein I tookfrom dusky dolphins landed at Pucusana (120 30' S)and Cerro Azul (13000' S), ports located 60 km and140 km, respectively, south of Lima, Peru. Estimatedpost-mortem time of specimens ranged from a fewhours to about 12 hours, exceptionally up to 18hours. The close examination of a few live-caughtanimals helped to define natural patterns and avoidrecording post-mortem artifacts. Data collection wasexecuted at all seasons in the period 1985-1990;many different herds, but apparently a single popu-lation, were sampled (VAN WAEREBEEK, 1992,1993). The long collecting period and sample sizeensured that most of the existing colour variationwas documented.

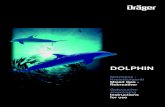

A series of 26 external measurements (Fig. 1),recorded to the nearest 0.5 cm and modified fromstandardized methods by NORRIS (1961), was ob-tained for 394 dusky dolphins (208 females, 186males) of all sizes. However, standard length wasavailable for 693 dolphins. Ten axial and nine point-to-point measurements of appendages were takenwith a semi-rigid metal tape (usually on the left sideof the body), and seven girths were measured witha flexible plastic tape. In a few cases, the fluke spanhad to be inferred from the width of a single fluke by

39Van Waerebeek. External Features of the dusky dolphin

FIG 1 External measurements taken of Peruvian dusky dolphins, including axial (nos. 1-10), girths (nos. 11-17) andpoint-to-point measurements (nos 18-26). Numbers in square brackets refer to equivalent variables of Norris (1961).

(1) Standard lenght: tip of upper jaw to deepest part of (15) Girth, at posterior insertion of dorsal fin.notch between flukes. [1] (16) Girth, at level of anus. [23]

(2) Length of gape: tip of upper jaw to angle of gape [3] (17) Girth, at midpoint between anus and deepest part of(3) Length, tip of upper jaw to center of eye. [2] notch between flukes.(4) Length, tip of upper jaw to posterior edge of blowhole (18) Length base of dorsal fin. [33](5) Length, tip of upper jaw to external auditory meatus. (19) Height of dorsal fin: fin tip to base. [32]

[5] (20) Maximum width of left flipper [31](6) Length, tip of upper jaw to tip of dorsal fin. [11] (21) Width of left flipper base at insertion.(7) Length, tip of upper jaw to anterior insertion of flipper. (22) Anterior length left flipper, from anterior insertion to

[10] tip. [29](8) Length, tip of upper jaw to midpoint of umbilicus [12] (23) Posterior length left flipper, from axilla to tip. [30](9) Length, tip of upper jaw to anterior border of genital (24) Length of fluke: from insertion to tip of left fluke

slit. (25) Depth of fluke: shortest distance from notch to anterior(10) Length, tip of upper jaw to midpoint of anus. [14] border of fluke. [35](11) Girth, at level of eyes. (26) Fluke span width of from tip to tip. [34](12) Girth, at level of axilla. [21] (27) Number of visible teeth: upper left.(13) Girth, at midpoint between axilla and anterior insertion (28) Number of visible teeth: upper rigth.

of dorsal fin (29) Number of visible teeth: lower left(14) Girth, at anterior insertion of dorsal fin. [22] (30) Number of visible teeth: lower right.

doubling this value. One of the girths (N° 17) wasabandoned for not having been taken rigorouslythroughout the study. A dorsal fin contour (DFC) wasobtained for 119 sexually mature dolphins (51 fe-males, 68 males) and 67 immature specimens (22females, 45 males). Gonads were examined when-ever available to determine maturity status.

When feasible, a colour pattern data form wasfilled out in situ. Colour transparencies (35 mm; 100ASA) were taken by daylight of the freshest speci-mens only; unusual patterns were documented by

the best means available. Contrast and vividness ofcolours improved considerably after carcases weredoused for a few moments with running seawater.Because the colour pattern was bilateral symmetric-al, only a single side (usually the left) was photogra-phed. Transparencies of 257 Peruvian dusky dol-phins were of sufficient quality to be used in acomparative study. For reasons of space, data arepresented here in summarized form; the raw data setis deposited at the Centro Peruano de EstudiosCetol6gicos (CEPEC), Pucusana, Peru.

Van Waerebeek. External Features of the dusky dolphin 41

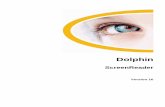

fully applied by EVANS (1975) for the common dol-phin Delphinus delphis, in which colour compo-nents (fields) are scored for large series of speci-mens (N > 100) Despite the generally subtle, non-<iiscre-

te variation encountered in the dusky dolphin, vari-ants of eight colour components were defined forwhich variation was most straightforward (Fig. 3;general terminology taken from MITCHEll, 1970):

FIG. 3. Colour pattern of the dusky dolphin, slightly modi-fied from Mitchell (1970), with AF= abdominal field, DFB =dorsal fin blaze, dfb = dorsal flank blaze, EYEP = eyepatch,FLAP = flank patch, FLiB = flipper blaze, FLiS = flipper

stripe, LLiP = lower lippatch, SF = spinal field, THO =

thoracic field

prominently black, covering (almost) entirelength of gape;

YELLOW FRINGE (YEL)1.: 1 = unmistakable brown-

yellowish hue visible in interface of abdominalfield with thoracic field and LLlP, occasionally atinterface of thoracic and dorsal fields; 2 = yello-

wish hue not clearly visible or absent;FLIPPER STRIPE (FLIS)2: 1 = moderately visible to

very prominent, light to dark grey band extendingfrom anterior insertion of flipper to EYEP; 2 =

flipper stripe absent or hardly discernible.

Transparencies were viewed with daylight slideviewers and characters were scored independentlyby Laura Chavez (University of Hamburg, Germany)who had field experience with the study species andI. Diverging scores were re-evaluated and, in theabsence of an immediate consensus, the characterwas left blank for that specimen

Because of indications of observer drift over timein character state definition, scores recorded directlyon the field but not supported by photographic mate-rial were not further considered, except for the "pro-minent" state (score 1) of characters YEL and FLISwhich were deemed unequivocal. Differencesamong sex and maturity groups were tested with X2

contingency analyses.

Other populations

Original data on adult body lengths and photogra-phic material of L. obscurus from other regionswere generously supplied by several researchers(see acknowledgements). Limited morphometric in-formation for New Zealand dusky dolphins has beenpresented by WEBBER (1987) in processed form.Additional photographs were consulted in the litera-ture: WORSIG & WORSIG (1978), GASKIN (1982),BAKER (1983), LEATHERWOOD & REEVES(1983), MINASIAN et al. (1984), HARRISON &BRYDEN (1988); QUAYLE (1988); WORSIG et al.(1989); WEBBER & LEATHERWOOD (1990) andWORSIG (1991). The characterization of geogra-phic variation in colouration I offer here is prelimi-nary. A quantitative analysis was deemed prematurebecause of small and heterogeneous samples (e.g.live animals besides specimens of variable post-mortem time) and unverifiable identity of specimensphotographed at sea (i.e. a single individual mayappear on different frames).

DORSAL FIN BLAZE (DFB): 1 = a very conspi-

cuous, whitish patch covering most of the dorsalfin; 2 = muted but clearly present, mostly lightgrey; 3 = hardly or not visible; dorsal fin usually

dark grey to blackish overall;FLIPPER BLAZE (FLIB): 1 = flipper uniformly light

grey, without contrasting trailing edge; 2 = flipper

light to dark grey with contrasting blackish trailingedge and flipper tip; 3 = dorsal surface of flipper

almost uniformly dark grey to black;EYE PATCH (EYEP): 1 = hardly noticeable, or very

lightly coloured; 2 = prominent, dark grey to

black;FLANK PATCH (FLAP): 1 = white of flank patch and

abdominal field (AF) blend into each other; 2 =

FLAP and AF separated by grey to blackish,ill-defined stripe of varying width; 3 = FLAP and

AF separated by broad uninterrupted, blackish

band;THORACIC FIELD (THO): 1 = entirely white, conti-

nuous with abdominal field, extending above flip-per and often even above eye; 2 = anterior part

of THO above flipper greyish, posterior part whiteand, laterally, gradually fusing with abdominalfield without a clear dividing line; 3 = entire THO

light or dark grey, demarcation with abdominalfield fairly sharp;

LOWER LIP PATCH (LLlP): 1 = greyish, minimumdefinition; 2 = dark grey, moderately defined,extending over two thirds of length of gape; 3 =

1 Data exclusively based on direct field observations

(data form).20ata partly based on direct field observations

42 Estud. Oceanol. 12, 1993

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

External size and shape

Individual variation

Taking into account the robustness of t -tests andANCOVAs (WONNACOTT & WONNACOTT, 1969),none of the 29 variables for either sex showed unac-ceptable departure from normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov, p> 0.01), bar the lower right tooth count formales. The latter, however, may be due to chancefluctuation because of the large number of t-testsperformed. Two character pairs (E1 0 and E26) devi-ated slightly from the required homogeneity of vari-ance between sexes (0.01 < P < 0.05), but one or two

pairs were expected to do so by chance at the 0.05level of significance. Statistics of individual variationin external measurements and counts of visible teethare presented for 220 sexually mature Peruviandusky dolphins (126 females, 94 males) in Table 1.Considerable variation was observed in the size andshape of the dorsal fin (Fig. 2) as discussed in detailbelow. A keel on the caudal peduncle as in theAtlantic white-sided dolphin Lagenorhynchus acu-

ius (e.g. LEATHERWOOD & REEVES, 1983) wasnot present.

(GOULD, 1966) and L. obscurus is no exception.Growth is characterized by least-squares regressionequations of the form Y = b.xa, where Y is a particu-

lar body measurement, X is total body length, a is thegrowth coefficient and b is a constant (Table 2).During ontogeny, body dimensions change eitherisometrically (a < 1) or allometrically with total length;

in the latter case the growth rate can taper off withincreasing length (a < 1) or intensify (a > 1) (see also

CLARKE & PALIZA, 1972; PERRIN, 1975).In L. obscurus, measurements of the anterior

body (snout to gape, eye, blowhole, ear and toflipper insertion), as well as the size of the flippersand the length and depth of the flukes, follow apattern in which growth declines in intensity withincreasing total length (Fig. 4). The span of flukesand the base and height of the dorsal fin are charac-terized by a positive allometric growth. Developmentin girths ranges from a diminishing growth at thelevel of the eyes, and a roughly isometric expansionat mid-body (from axillae to dorsal fin), to an in-creased growth in the body posterior to the dorsal fin

(Fig. 4).The growth rate (slope) is significantly different

between sexes in 12 of 24 variables (Table 2). Thetype of growth allometry (positive or negative), how-ever, is equal in males and females, with the possi-ble exception of girth at axillae (E12). Individualvariation is negligible in juveniles, but it is greatlyamplified in adult animals, a feature also found inoceanic dolphins of the genus Stenel/a (PERRIN,

1975).

Sexual dimorphism

I found no statistically significant difference (t =1.68; P = 0.09) in total body length between adult

females and males. Alternatively, small but highlysignificant differences (p < 0.005; t-tests and ANCQ-

VAs) were present in six body measurements,namely: girth at anus, maximum width of flipper,base length of dorsal fin, depth of flukes (all greaterin males), snout to vent and snout to anus (greaterin females). Some proportional dimorphism was ap-parent also in the anterior and posterior length of theflipper and the length of the fluke, which were some-what greater in males than in females (ANCQV A,P < 0.05). The slightly greater absolute values for

maximum girth (E13, Table 1) and girth in front of thedorsal fin (E14) in females (t-tests, p < 0.05) are

direct consequence of the bigger size of the femalesin the sample; indeed, corresponding F-statistics(ANCQVA) are not significant. All measurementswere highly correlated with the body length covariate(ANCQVAs, p < 0.0005). Tooth counts, logically,

showed no significant correlation (ANCQV As,0.30 < P < 0,70).

Variation in the dorsal fin

Males have a broader-based dorsal fin than fe-males (E18, t = 3.31, P > 0.002), but there is nosignificant difference in fin height (E19, t = 0.34, P =

0.74). Also, the tip of the dorsal fin is markedly lesserect, so the fin is more hooked (F = 12.2; df 1, 118;P < 0,001) in mature males (mean elevation a =49,6°, SE = 0,66°), than in females (mean a = 53,2°,SE = 0,83°). In addition, the dorsal fin becomes more

hooked with increasing body length (SL); a linearregression with sexes pooled of dorsal fin tip eleva-tion against standard body length (SL, in cm) yieldedthe following highly significant correlation:

a = 69,7° - 0,097 (SL) (F = 20,6; df 1, 182; P < 0,0001).

However, only 10.2% (r) of total variation wasexplained by the model. The large residua! variationis believed to represent measuring error caused bydifficulties in determining the correct base line on theDFC sheets; with a more accurate method for meas-uring fin angles, r is expected to improve. Nothing

Developmental variation

Developmental change in body proportions is awidespread phenomenon among mammals

~.t:U~'E0t:Q)

01cu

...Jc:-0In

.-

c:"'iU:c

"::

.Q.~

0-U

o>

~c:

1n0):J

'(3U

.-

~~~o

O)u

II II

~>0)0

roo+-'

E ~

u~c: ,-C

Uu

~O

)

<D

c:(\1.-

-~

O)

II U

z~~cu

.9l.cu~

C

U"::

WE

2-I

0)..::

oo-u«~

>.

I-:J'E"':Jcu...

E

cu

.:2:-~

ro~:JO

)X

...

O)cu

In ~-O

c:cu

In .-

"'>C::J

:J,-

00)

Uc..

.1::-

"'CU

0,-

0'"...C

:

uO)

c:UcuE

~oE-=

u -

c: III

=2In

:3"'Uc:

III

O).Q

Eo

~:JIncu0)Eroc:'-0)

xW

cnW-l~~wu.

(/JW-l«~

W-.Jm«~~

z w(9z«[t: z<w~ 0(/)

>u z w~z«[l: z«w~ 0cn >1

WM

W~

WM

N

~V

ww

~m

m~

wm

mw

~~

w

mm

mN

WU

M

~V

~V

V~

VV

VM

VV

VW

~W

WV

~V

~~

~~

~W

W~

0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

Van W

aerebeek. E

W~

~O

OO

NO

MM

~~

OO

M~

~~

~w

~~

~~

mow

ooooN

OO

Om

mO

mm

mN

~~

~~

NO

mO

OO

Om

omoooooooo

~~

~~

~

~

~~

~~

~~

~

~~

~

~

It) It)

It)It)

It) ~

cD

M

Q)

1t)1(jr--:a>

~~

~

It) It)

OV

Q)~

It)N~

Q)M

VIt)~

NN

O~

MM

~M

~~

VIt)It)W

It)NM

NN

NM

M~

VQ

)~~

~~

~~

~~

MN

~~

MN

M~

It)MM

MM

oom~

~~

~~

oo~~

~~

6~6~

~~

m~

~6~

6~~

~~

~w

~

"NN

"M

~

"N

" "0

"a>

"" ""N

N

vNN

NN

~

~

N

W~

~Q

)~Q

) M

M~

O

a>

~

N

0 0

Wa>

Q

) It)N

~

N~

~

OW

~W

OM

~V

~M

wm

~ovW

OM

M~

VM

W~

M~

W~

~m

~~

~~

~N

W~

~~

M~

NM

Nm

mO

~M

~O

NW

mm

WW

WN

NN

M~

vWM

MW

O~

~m

WN

~~

~M

NM

~V

NN

NN

~

~

~~

~

~~

~m

~m

~oo

~O

ON

~

MW

NM

W~

~M

~~

~~

OO

~~

M~

~~

~M

~~

~M

M~

~~

W~

OO

OO

~~

~~

~W

WW

WW

~00000000000000000000000000000

00000000000000000000000000000

VM

VM

~~

N~

V~

~om

OO

~M

MM

MN

Nm

~v~

~~

rom

rororo~~

ro~~

~roro~

rororororororororo~roro~

~~

~

Ll) Ll)

Ll) Ll)

ai~~

Ll)m

Ll) cD

MLl)II>

.-NC

D

~Ll)

OLl)O

O'-V

Nm

Ll).-Ll)v.-NN

OLl)~

~.-M

OO

OO

CD

Ll)mC

DC

DM

MN

NN

MM

.-vm

~

~M

N

MN

M.-Ll)M

MM

M,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

Ll)Ll)Ll)VO

OLl)Ll)O

Vv.-Ll)m

OO

OO

Ll)CD

mO

Ll)OLl)Ll)O

CD

CD

Ll)Ll)lI>

aiNN

NN

~oom

NC

D~

mO

OO

Ll)~.-

'-aiNw

6VN

NN

N~

.-N

OM

.-

m'-

N

N

N.-

.- .-

vvoo~~

oovvomoovO

ON

mM

NV

~oooo~

~~

m~

M~

V~

~~

~O

~N

~O

O~

~M

mO

~~

Om

O~

M~

~N

OO

mm

OO

OO

OO

NN

NM

~V

OO

OM

WO

O~

mW

M~

~~

MN

M~

VN

NN

N~

~

~

~

~~

~

M

m

~O

ON

~~

Nv

VM

~M

N~

M~

~~

~M

MO

O~

~~

NM

Vm

~~

OO

mV

~N

VM

~~

~~

~~

NO

OO

OO

O~

O~

~~

~~

~~

~N

M~

~N

~~

~~

MN

~O

O~

~~

OM

~N

~~

al Features of the dusky dolphin

~

~

c: Q

I ~

QI

c: I;::

a. Q

la. -

o:?:- C

:c: -

a. a.a.

.c:-.-

~

I;:: I;::

m

=

QI

a..- 4::

OJ

4:: .c:

a. t

0 -

- U

! -

U!

- 10=

Q

I .-

QI

OJ

~

QI.':

m

m

~

c: -

m

10=

- -

~

- .:

QI

c:U!U

!2 ~

~

OI;::°.D

oo W

W~

~-

I;::.~:J

c: 0

0 "C

ro

.c: ~

:E

a. a.

QI

QI

:5 0

- ~

.~

m

U

! Q

I .c: "C"C

0

U! - Q

I :5 OJ Q

I QI

a. a. ~

~~

QI

~

mQ

l=

-~U

!mt-

U!

~:2a.~

c:~

~

~~

oo~

, >

U

! a..D

-

~

- .-

"C

.c: 0:>

~

, ~

~

~

~

-

-

c: a.

QI

0 ~

~

a.

Ec:

c: Q

I =

O

J c:

c: :J

- "C

>

.9-

c: ~

10=

~

c:

.c: .c:

.c: .c:

QI

m

>-

- m

0

.- Q

I m

>

- >

<E

o -

c: O

JE

10=

QI

- - m

- - - --O

JQI.D

QI"C

IO=

:J>oQ

lm

~.c:m

c:o --50-a.Q

IQIQ

IQI

"E

0 0

0 0

0 0

0 0

- ro

ro :J

c: 2

ro ~

-

:J 0

5 ":

.c: 0

U!

2 2

2 2

m - - - - - - - - -

E

.- .c:

E

.c: .:

QI -

.c:Q

I- - - -"C

- - - - - - - - :J

.c: .c: ._><

.c: .c:

.c: Q

I O

J ._><

- Q

I -

OJ

- ~

0

0 0

0c:

:J :J

:J :J

:J :J

:J :J

0 -

- -

- -

U!.-

"C

- U

! c:

a.0

0 0

0 0

0 0

0 c:

.: .:

m

.: .:

.: m

Q

I m

.-

c: 0

QI

QI

:J ~

~

~

~

2c:c:c:c:c:c:c:c:w~

~~

~~

~~

I~~

<~

~o~

2222W

W

W

W

W

W

W

W

W

..

.. ..

.. ..

.. ..

.. ...

.. ..

.. ..

..E

EE

E..O

.-NM

"3"LO(cC

X>

o)O.-N

M"3"LO

(c~

NM

"3"LO~

~C

X>

o)~'-'-'-'-'-'-'-'-N

NN

NN

NN

:J:J:J:Jw

ww

ww

ww

ww

ww

ww

ww

ww

ww

ww

ww

ww

zzzz

43

wm

~w

~

N~

Wm

~N

~N

~~

~~

~~

m~

w~

~

M~

ON

MM

W~

~~

N~

~M

OW

m~

MW

~W

~N

~~

mm

OW

o~

~~

~~

~N

~~

~N

~~

~~

~N

~O

O~

~~

ON

~N

~N

Van Waerebeek. External Features of the dusky dolphin 45

TABLE 2Growth pattern external measurements (VAR, see Table 1) in function of total body length (X)

in Lagenorhynchus obscurus of Peru. Least-squares regression power equations andcoefficient of determination (~) are indicated for females and males separately. All equationshave highly significant slopes (ANVOVAs, covariate p < 0.0002). Significance level of sexual

dimorphism in slope is indicated (ns = not significant). Growth equations not significantly

different (95% C.I.) from the linear model are marked by L.

FEMALESEquation Y=

MALESEquation Y=

Dimorphismpr2Var r2

0.27 XO840.36 XO810.23 XO92

0.51 XO780.77 XO960.58 XO820.71 XO920.77 XO970.68 X1.011.44 XO.730.51 X1.01 (L)0.52 X102 (L)0.52 X102 (L)0.24 X1130.19 X110

0.12 X1040.09 X103 (L)0.077 XO940.14 XO850.32 XO890.20 XO.910.31 XO.880.19 XO790.12 X114

0.16 XO93

0.26 XO880.16 XO99 (L)0.45 XO810.68 XO98 (L)0.41 XO890.64 XO940.74XO950.70 X100 (L)1.37Xo.750.64 XO970.63 XO98 (L)0.61 XO99 (L)0.41 X103 (L)0.24 X1070.11 X1070.05 X1130.10 XO880.094 XO.920.27 XO.920.17 XO.950.19 XO97 (L)0.13 XO880.13 X113

E2E3E4E5E6E7E8E9E10E11E12E13E14E15E16E18E19E20E21E22E23E24E25E26

939394939896999999958596959495939395959695949396

92.6

92.894.591.198.696.198.898.999.497.396.596.796.895.095.693.693.095.795.396.293.894.593.094.6

< 0.005< 0.01< 0.05ns< 0.05< 0.005nsnsnsns< 0.05nsns< 0.005nsns< 0.01< 0.005< 0.005nsns< 0.005< 0.005ns

Dusky dolphins from southwestern Africa, with amean adult length of 179.9 cm (SD = 718 cm, N =

20, sexes pooled) and a maximum recorded lengthof 1905 cm (N = 58) (P.B. BEST, South AfricanMuseum, unpubl. data), are comparable in size (t =0.29, P = 0.77) to mature animals from New Zealandwhich average 179.1 cm (SD = 8.97 cm, N = 12) and

attain a maximum length of 195.5 cm (data providedby A.N. BAKER, National Museum of New Zealandand P.J.H. VAN BREE, Zoological Museum, Univer-sity of Amsterdam). SW African and New Zealanddusky dolphins each are noticeably smaller thantheir Peruvian counterparts (t-tests, p < 0.0001);

mean and maximum lengths differ some 8-10 cm.This further supports conclusions from cranial vari-ation analysis that these groups constitute separatepopulations, and possibly even valid subspecies.Despite a few (statistically) significant cranial differ-

ences, Peruvian and Chilean dusky dolphins prob-ably form a single SE Pacific population (VANWAEREBEEK, 1992, 1993). A greater sample fromChile is needed to permit a definitive conclusion.Little can be said about L. obscurus from Argentina,due to an almost total lack of data. Body lengths oftwo females of unknown maturity have been publish-ed: one 162.5 cm and the other 165.5 cm (WATER-HOUSE, 1838; LAHILLE, 1901). The standard bodylength of a specimen discussed by GALLARDO(1912) probably was 175.5 cm (GALLARDO's"100%"), and not 183 cm ("maximum length,104,6%") as interpreted by KELLOGG (1941).

Colouration

Variation within the Peruvian population

Individual variation in colouration is extensive

.4

.7

.4

.6

.9

.8

.1

.0

.7

.1

.0

.7

.5

.0

.1

.3

.2

.9

.6

.4

.7

.9

.0

.6

Van Waerebeek. External Features of the dusky dolphin 47

(Chubut, Argentina) also greatly vary in degree ofmelanisation, possibly even more so than in Peru(see WORSIG & WORSIG, 1978; 64,66). In a heav-ily melanised phenotype, upper and lower lippatches and the eye patch are strikingly black; aconspicuous flipper stripe forms a broad, continuousblack band that fuses with an equally dark flipper.The dorsal fin is almost entirely black and a yel-lowishbrown hue of varying intensity may line theborders of the white fields along the body In a light-col-oured phenotype, the flipper, flipper stripe, eye patchand lip patches are so faintly pigmented as to appearalmost absent (e.g. GALLARDO, 1912; WORSIG &WORSIG, 1978). Limited photographic material sug-gests that the frequency of occurrence of these pheno-types may be group-specific; moreover most specimensseem to be intergrades between the two extreme types.

In live animals the anterior portion of the dorsalflank blaze (dfb) is visible anterodorsally some dis-tance beyond the dorsal fin. Due to quick post-mor-tem fading this trait was rarely obvious in the Peru-vian specimens.

Fitzroy form

A female dusky dolphin harpooned from the Bea-gle in Bahia San Jose (Argentina), was described byWATERHOUSE (1838) as Delphinus fitzroyi, sub-sequently referred to the genus Lagenorhynchusby FLOWER (1885). After more than a century ofconfusion (reviewed by HERSHKOVITZ, 1966) L.fitzroyi was still considered a separate species byfor instance NISHIWAKI & NORRIS (1966). Otherauthors including KELLOGG (1941), yANEZ (1948)and FRASER (1966) justly synonimized it with L.obscurus. More recently it has been regarded bysome authors as a separate "Fitzroy" colour form ofthe dusky dolphin (WATSON, 1981; LICHTER &HOOPER, 1984; MINASIAN etal.1984; CARDENASet al., 1986). For reasons of clarity I reproduce here(my comments in square brackets) the original descrip-tion of the colour pattem by WATERHOUSE (1838):

"Upper parts of the body black, under parts purewhite, the two blended into each other by gray:extremity of snout a ring round the eye [EYEP =2], the edge of the under lip, and the tail fin, black[LLIP = 3]; dorsal [DFB = 3] and pectoral fins[FLIB = 3] dark gray; a mark extends from theangle of the mouth to the pectoral fin [FLIS = 1];above which, the white runs through the eye andis blended into grey over the eye; two broaddeep-gray bands are extended in an obliquemanner along each side of the body, runningfrom the back downwards and backwards [FLAP= 1 or 2]".

ceptionally (8 of 208, 3.8%) the white of both fieldsblend clearly into each other. The frequency of FLAPvariants had no relation to either sex (X2 = 1.42; df 2;P = 0.49) or maturity (X2 = 2.39; df 2; P = 0.30) of the

dolphins.THORACIC FIELD-. The most common form of

thoracic field in present sample (111 of 190,58.4%)was pigmented overall and therefore clearly differen-tiated from the ventral field; in ten animals (5.3%) thethoracic field appeared mostly white, while 69 speci-mens (36.3%) were intermediately coloured. Theintensity of pigmentation was independent of matu-rity (X2 = 0.70; df2; P = 0.70) and sex (X2 = 4.37; df2; P = 0.11).

LOWERLIP PA TCH-. Of 167 dusky dolphins ex-amined, 22 (13.2%) showed a lower lip patch (LLIP)with minimal pigmentation; 93 (55.7%) had a moder-

ately pigmented and 52 (31.1 %) a heavily pigmentedLLiP. Sexual dimorphism was absent (X2 = 2.88; df2; P = 0.24), but juveniles had a less pigmentedlower lip than adults (x2 = 13.37; df 2; P = 0.0013).

YELLOW FRINGE-. A brown-yellowish lateralfringe (YEL) was clearly visible in 33 of 190 (17.4%)dolphins. A first x2 test classified this trait as inde-pendent of sex and maturity, but statistical valueswere lost and could not be re-calculated since thedata set was unaccessible at time of writing.

FLIPPER STRIPE-. The presence of a prominenteye to flipper stripe was fairly infrequent, namely in36 of 224 (or 16.1%) of individuals examined. Thefrequency of occurrence was independent of sex(X2 = 3.06; df 1; P = 0.08) and maturity (X2 = 0; df 1,P = 1.00, with Yates' correction).

Geographic variation

Variants of colour fields in New Zealand duskydolphins, evaluated from photographic material ofmostly live animals, were not qualitatively differentfrom these found in Peruvian specimens. As indi-cated earlier, no quantitative analysis was possible,but the form with an entirely white thoracic patch(THO = 1), relatively rare in Peru (5.3%), may be the

more common form in New Zealand. DAWSON(1985), discussing the latter, referred to the thoracicpatch as "a blaze of white extending from the snout,above the eye, and along the flank to join the whiteof the belly", coinciding with our THO = 1 definition.

Several L. obscurus specimens from New Zealandpresented a (to Peruvian standards) unusually smalland delicate flank patch. A comparison of coloura-tion with SW African dusky dolphins also revealedno obvious deviations from the pattern seen in Peru-vian animals, but further research is necessary.

Dusky dolphins from the Peninsula Valdez area

48 Estud. Oceanol. 12, 1993

The description and the accompanying litho-graph made by Captain Fitzory "after an excellentcoloured drawing, when fresh killed" indicates thatthe Fitzroy specimen is similar to the heavily melan-ised colour type, as referred to above, from photo-graphs presented by WURSIG & WURSIG (1978).The reported colouration of the Fitzroy specimen isaberrant in that "the white runs throught the eye" andin the unusual, indistinct shape of the flank patch(see WATERHOUSE, 1838: plate 10). The animalwas either an anomalous case of the melanised formor, despite claims by WATERHOUSE (op. cit.), hasnot been accurately depicted. The flank patch of theGALLARDO (1912, Fig. 1) specimen was also fairlyunusual, so perhaps this patch is more variable inArgentinian than in Peruvian L. obscurus. If in anadequate sample from Argentina, the melanisedform would prove to be a discrete phenotype, it couldbe referred to as the "Fitzroy form"; if not, and in themeantime, this name should be reserved for histori-cal reviews only.

Anomalous pigmentation

Five Peruvian dusky dolphins and one specimenfrom SW Africa showed anomalous piebald pigmen-tation in the form of irregular white flecks of blotchessuperposed on the normal pattern (Table 3). Whitepatches on (black) skin have been associated withCandida spp. infections in captive SW African duskydolphins (FOTHERGill & JOGESSAR, 1986), butthe abnormalities reported here were presumably

not of an infectious nature, since the affected skinsurface was smooth and apparently healthy. Thephenotypic condition is highly reminiscent and prob-ably equivalent to piebaldness (Dr. P.JH. VANBREE, in liff. 19 May 1992), a genetic melanisationdefect well-known in humans and domestic animals,also referred to as "Weiszscheckung" or "partial albi-nism" (SUNDFOR, 1939; HOEDE, 1940; COOKE,1952; COMINGS & ODLAND, 1966; HUL TEN et al.1987). Probability considerations suggest consan-guinity for two affected animals (one a severe case)landed the same day at the Pucusana wharf (Table3). Differential frequencies of this dominantly inher-ited trait perhaps could help delineate local breedinggroups, however for large-scale population discrimi-nation (e.g. Peru versus SW Africa) it is probablyuseless. Indeed, its occurrence in humans of variousraces and widely separated areas suggest that it canarise, apart from direct inheritance, by new mutation(see SUNDFOR, 1939). Whether piebaldness isidentical with Chidiak-Higashi syndrome, previouslyreported from a killer whale (RIDGWAY, 1976,quoted in MATKIN & LEATHERWOOD, 1986,Fig. 3.3) is still unclear. In any case, the partialskin melanisation and the normal pigmentationof the eyes clearly distinguishes it from albinism(see HOE DE, 1940; HAIN & LEATHERWOOD,

1982).In the genus Lagenorhynchus aberrant pigmen-

tation, but not piebald ness, has otherwise been de-scribed solely from L. ob/;qu;dens (BROWN &NORRIS, 1956; BROWNELL, 1965; BLACK, 1989

TABLE 3Known cases of piebald colouration in Lagenorhynchus obscurus

Date Sex Description and sourceNumber Locality SL(cm)

Sept. 85 ?Anc6n, Perus.n

Pucusana,Peru

Pucusana,Peru

Aug. 86 ? ?s.n

KVW1018 25 Dec. 87 M 194.5

KVW1288 PucusanaPeru

2 Jun. 88 M 190.0

KVW1313 Pucusana,Peru

SAM37754 Hout Bay,South Africa

2 Jun. 88 F 196.0

white blotches on anterior body and lowerlip; photograph by J.C. Reyes (CEPEC)

white blotches on flukes and tail stock; pho-tograph by J.C Reyes (CEPEC)

blotches on flank and thoracic patch, dorsalflank blaze absent; photographs by author,skin sample

flecked pattern over most of body, super-posed on normal pattern; photographs byauthor, skin sample

flecked patches; photograph by author

7 Mar. 76 F 168.0 unpublished photograph courtesy of Dr. P.B.Best (South African Museum, Cape Town)

Van Waerebeek. External Features of the dusky dolphin 49

CONCLUSIONS level and sample size (so-called 13 error, see WON-NACOTT & WONNACOTT, 1990), may be fairlyhigh. At any rate differences are subtle at best, andone may safely state that, based on size, shape andcolouration, female and male dusky dolphins arehard to distinguish from each other. This fact, toge-ther with equal length at (50%) sexual maturity formales and females (175 cm), huge testis size, andapparent absence of wide-spread male antagonisticbehaviour suggests a promiscuous mating systemwith sperm competition in the dusky dolphin (VANWAEREBEEK, 1992; VAN WAEREBEEK & READ,in press).

Of eight colour components tested, the flipperpatch, lower lip patch and eye patch are substan-tially less pigmented in juveniles than in adults. Fullpigmentation, at least in some elements of the colourpattern, tends to be reached only at maturity, whichis in agreement with findings for other delphinids.WALKER et al. (1984, 1986) found muted expres-sion of elements of the adult colour pattern in foe-tuses and newborn calves of the Pacific white-sideddolphin and intensification with age. PERRIN (1972)noted a progressive obscuring of the dorsal cape inthe spinner dolphin. GWINN & PERRIN (197~)through microscopic examination found some evi-dence of pigment aggregation with development, inthe epidermis of gray and black areas of the com-mon dolphin. Yellowish-brown pigment is rare incetaceans and has been reported only from thecommon dolphin, the Atlantic white-sided dolphinLagenorhynchus acutus and some young speci-mens of the killer whale (MITCHELL, 1970; GWINNAND PERRIN, 1975; ELLIS, 1989). Thus the discov-ery of a yellow fringe in L. obscurus is not withoutimportance. Although our current colouration recordfor the various populations is incomplete, there areindications that divergences may exist in relativefrequencies of colouration pattern variants.

The striking differences in mean and asymptoticbody length between Peruvian and both New Zea-land and SW African dusky dolphins support therecognition of discrete populations (and possiblyeven separate subspecies) based on craniometricand geographic considerations (VAN WAERE-BEEK, 1992, 1993).

Although sexual dimorphism is statistically signifi-cant in several external measurements, only differ-ences in the position of the genital slit and anus andthe shape/size of the dorsal fin are of sufficientmagnitude to manifest a biological function. Themore forward positioned genital aperture and anusin male dusky dolphins are typical cetacean features

(e.g. SERGEANT, 1962b; SL/JPER, 1962; PERRIN,1975; YONEKURA et al. 1980). The slightly greatergirth at the anus in males can be related to this.There is no vertical thickening of the caudal stockbehind the anus as for instance is seen in maturemales of the eastern spinner dolphin Stenel/a longi-rostris orientalis (PERRIN, 1975; PERRIN et al.1991 ).

The dorsal fin of the male is more strongly curvedand broader-based and has a substantially greatersurface area than that of the female. These dispari-ties are accentuated with increasing body length. Ipropose that the dorsal fin, besides its hydrodynamicfunction, serves as a secondary sexual character, amorphological signature of sexual maturity and, indi-rectly, social status. In any case, the dorsal fin of L.obscurus is more variable than either its flippers offlukes, which suggests that additional selective pres-sures are at work. The same argument probablygoes for various other cetaceans, including killerwhales, eastern spinner dolphins, Dall's porpoisesPhocoenoides dal/i (JEFFERSON, 1990; PERRINet al., 1991) and Pacific white-sided dolphins(BROWN & NORRIS, 1956). In adult spinner dol-phins and Dall's porpoises, males have a more ere.ctdorsal fin than females (JEFFERSON, 1990; PER"::-RIN, 1990; PERRIN et al., 1979, 1991). The reverseis true for the dusky dolphin and, possibly, the Pacific

white-sided dolphin Other Lagenorhynchus spp.

should be checked to see whether this trait is idio-syncratic for the genus. Unfortunately, individualvariation and overlap in dorsal fin size and shape aretoo great to permit reliable sexing of free-rangingdusky dolphins. In killer whales, gender has beenjudged on the basis of ratio of dorsal fin height tobasal length, although that method as well wasthought not to be foolproof (MATKIN & LEATHER-

WOOD, 1986).No significant sexual dimorphism was found in

the colouration of L. obscurus. However, it is per-haps worth to warn here for undue definitive conclu-sions concerning (absence of) dimorphism whereborderline values for p were found (e.g. eye patchand measurements E8 and E24, with 0.05 P ~ 0.07)since the probability that these characteristics are

slightly dimorphic but were not detected at chosen a

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I owe special thanks to J.C. Reyes for his long-term assistance in the field, and to Dr. P.J.H. vanBree and T. Luscombe for advice and logistical sup-port. I extend my gratitude also to J. Alfaro, Dr. M.F.Van Bressem, L. Chavez, A.C. Lescrauwaet, Dr.

Estud. Oceanol. 12, 199350

A.J. Read and to M. Chandler, L. Lehman and J.S.McKinnon, who for varying periods helped withmeasuring dolphins. Photographic material and un-published data were courteously put at my disposi-tion by Dr. A.N. Baker, Dr. P.B. Best, Dr. P.J.H. vanBree, Dr. S. Leatherwood, M. Webber and Dr. B.Wursig, to whom I extend my most sincere thanks.Dr. W.F. Perrin, Dr. J.H. van Bree, and Dr. J.H. Stockmade valuable comments on an earlier version ofthe manuscript. Present study was supported bygrants from the Whale and Dolphin ConservationSociety (WDCS) and the King Leopold III Fund forNature Research and Conservation. Additional fund-ing was provided by IUCN/UNEP, BBC-WildlifeMagazine, Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tec-nologia (CONCYTEC, Peru), and the Van Tien-

hoven Foundation.

REFERENCES

ALLEN JF 1977. Dolphin reproduction in oceanariain Australasia and Indonesia. In Breeding Dol-phins, Present Status, Suggestions for the futu-re. SH Rigway & K Bernirschke (eds.). Rep.MMC-76/07 to US Marine Mammal Commission,

pp.85-100.ANDRADE H & P BAEZ 1980 Presencia del delfin

listado: Lagenorhynchus obscurus (GRAY, 1828)en la costa de Valparaiso Noticiero Mensual delMuseo Nacional de Historia Natural 288/289: 7-9.

BAIRD RW & PJ STACEY 1988 Variation in saddlepatch pigmentation in populations of killer wha-les (Orcinus orca) from British Columbia, Alas-ka, and Washington State. Canadian Journal ofZoology 66: 2582-85.

BAKER AN 1983. Whales and Dolphins of NewZealand and Australia. Victoria University Press,133 pp.

BIERMAN WH & EJ SLIJPER 1947. Remarks uponthe species of the genus Lagenorhynchus. Ko-ninklijke Nederlandse Akademie voor We-tenschappen50: 1353-64

BIERMAN WH & EJ SLIJPER 1948. Remarks uponthe species of the genus Lagenorhynchus. Ko-ninklijke Nederlandse Akademie voor We-tenschappen 51 (1): 127-33.

BINI G 1951. Osservazioni su alcuni mammiferi ma-rini sulle coste del Cile e del Peru. Boll. PescaPiscicultura Idrobiol 6 (n.s.) 1: 79-93.

BLACK N 1989. Pacific white-sided dolphins in Mon-terey Bay. Whalewatcher 23(1): 5-8.

BROWN DH & KS NORRIS 1956. Observations ofcaptive and wild cetaceans. Journal of Mamma-logy 37(3): 311-26.

BROWNELL RL Jr. 1965. An anomalous color pat-tern in a Pacific striped dolphin. Bulletin of theSouthern California Academy of Sciences64(4): 242-3.

BROWNELL RL Jr. 1974. Small odontocetes of theAntarctic. Antarctic Map Folio Series 18: 13-

19.CARDENAS JC, STUTZIN ME, OPORTO JA, CA-

BELLO C & D TORRES 1986. Manual de identi-ficaci6n de los cetaceos chilenos. CODEFF,Santiago, Chile, 102 pp.

CLARKE R & 0 PALIZA 1972. Sperm whales of theSoutheast Pacific. Part III: Morphometry. Hvalra-dets Skrifter 53. Det Norske Videnskap-Akade-mi I Oslo, 106 pp.

COMINGS DE & GF ORLAND 1966. Partial albi-nism. Jama 195 (7): 519-523.

COOKE JV 1952. Familial white skin spotting (Pie-baldness) ("Partial albinism") with white forelock.Journal of Pediatrics 41(1): 1-12.

DAWSON S 1985. The New Zealand Whale andDolphin Digest. Brick Row Publ. Co., Auckland,130 pp.

ELLIS R 1989. Dolphins and porpoises. A.A. Knopf,

New York, 270 pp.EVANS ME 1975. The biology of the common dol-

phin, Delphinus delphis, Linnaeus. Ph. D. the-

sis, University of California.EVANS WE, THOMAS JA & DB KENT 1984 A

study of pilot whales (Globicephala ma-crorhynchus) in the southern California bight.Admin. Report LJ-84-380, NMFS/SWFC, La Jo-lla, California, 47 pp.

EVANS WE, Y ABLOKOV A V & AE BOWLES 1982.Geographic variation in the color pattern of killerwhales. Reports of the International Whaling

Commission 32: 687-94.EVANS WE, THOMAS JA & DB KENT 1984. A

study of pilot whales (Globicephala ma-crorhynchus) in the southern California bight.Adm. Rep. LJ-84-380, NMFS/SWFC, La Jolla,California: 1-47.

FLOWER W 1885. List Cetacea of the British Mu-

seum. Proceedings of the Zoological Society,London.

FOTHERGILL M & VB JOGESSAR 1986. Haemato-logical changes in two Lagenorhynchus obs-curus treated with Ketoconazole. Aquatic Mam-

mals 12(3): 87-91.FRASER FC 1966. Comments on the Delphinoidea.

In Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises. KS Norris(ed.). University of California Press, Los Ange-

les, pp. 7-30.GALLARDO A 1912. EI delfin Lagenorhynchus

fitzroyi (Waterhouse) Flower, capturado en Mar

51Van Waerebeek. External Features of the dusky dolphin

Segregation of two forms of short-finned pilotwhales off the Pacific coast of Japan. ScientificReports of the Whales. Research Institute 39:

77-90.KELLOGG R 1941 On the identity of the porpoise

Sagmatias amblodon Field Museum of Natu-ral History, Zoological Series 27: 293-311 + 7

pis.LAHILLE F 1901 EI delfin de Fitzroy Lagenorhyn-

chus fitzroyi (Waterh.) Flow. Boletin de Agri-cultura y Ganaderia 1(4): Buenos Aires: 3-6

[Not seen].LEATHERWOOD S & RR REEVES 1983. The Sie-

rra Club Handbook of Whales and Dolphins. Sie-rra Club Books, San Francisco, 302 pp.

LICHTER A & A HOOPER 1984 Guia para el reco-nocimiento de cetaceos del Mar Argentino. Fun-daci6n Vida Silvestre Argentina, 96 pp.

MATKIN CO & S LEATHERWOOD 1986. Generalbiology of the killer whale. Orcinus orca: asynopsis of knowledge. In Behavioral Biology ofKiler Whales BC Kirkevold & JS Lockard (eds.).Alan R. Liss, Inc., New York, pp. 35-68.

MINASIAN SM, BALCOMB III KC & L FOSTER1984 The World's Whales. Smithsonian Institu-tion, 244 pp.

MITCHELL E 1970 Pigmentation pattern evolutionin delphinid cetaceans: an essay in adaptativecoloration. Canadian Journal of Zoology 48(4):717-40.

NISHIWAKI M & KS NORRIS 1966 A new genus,Peponocephala, for the odontocete cetaceanspecies Electra e/ectra. Scientific Reports ofthe Whales Research Institute 20: 95-100

NORRIS KS (ed.) 1961 Standardized methods formeasuring and recording data on the smallercetaceans. The Committee on Marine Mammals,American Society of Mammalogists. Journal ofMammalogy 42(4): 471-76.

PERRIN WF 1972. Color patterns of spinner porpoi-ses (Stenella cf. longirostris) of the easternPacific and Hawaii, with comments on delphinidpigmentation Fishery Bulletin of the Fish andWildlife Service US, 70: 983-1003

PERRIN WF 1975. Variation of spotted and spinnerporpoise (genus Stenella) in the eastern Pacificand Hawaii. Bulletin Scripps Institute of Ocea-nography 21: University of California Press,Berkeley, 206 pp.

PERRIN WF 1990. Subspecies of Stenella longi-rostris (Mammalia: Cetacea: Delphinidae) Pro-ceedings of the Biological Society of Wash-ington 103(2): 453-463.

PERRIN WF, AKIN PA & JV KASHIWADA 1991.Geographic variation in external morphology of

del Plata. Anales del Museo Nacional de His-toria Natural de Buenos Aires 23: 391-7.

GASKIN DE 1972 Whales, Dolphins and Seals:With Special Reference to the New Zealand Re-gion. Heinemann Educational Books, Londonand Auckland, 200 pp.

GASKIN DE 1982. The Ecology of Whales and Dol-phins Heinemann Educational Books, London,459 pp.

GOULD SJ 1966. Allometry and size in ontogenyand phylogeny Biological Reviews 41: 587-640.

GRAY JE 1828. Spicilegia Zoologica - Or originalfigures and short systematic descriptions of newand unfigured animals. London, pt. 1: 1-8.

GUERRA C, VAN WAEREBEEK K, PORTFLITT G& G LUNA 1987. Presencia de cetaceos frente ala segunda region de Chile. Estudios Oceano-16gicos 6: 87-96

GWINN S & WF PERRIN 1975 Distribution of mela-nin in the color pattern of Delphinus delphis(Cetacea; Delphinidae). Fishery Bulletin 73(2):439-44.

HAIN JHW & S LEATHERWOOD 1982 Two sight-ings of white pilot whales, Globicephala melae-na, and summarized records of anomalouslywhite cetaceans. Journal of Mammalogy 63(2):338-43.

HARRISON R & MM BRYDEN 1988. Whales, dol-phins and porpoises. Facts on File Publications,New York, 240 pp

HERSHKOVITZ P 1966. Catalog of living whales.Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.: 259pp.

HEYNING JE & WF PERRIN 1991. Re-examinationof two forms of common dolphins (genus Delphi-nus) from the eastern North Pacific; evidence fortwo species SWFC/NMFS Adm. Report. LJ-91-28, 37 pp

HOE DE K 1940 Erbpathologie der menschlichenHaut. In: Erbbiologie und Erbpathologie korperli-cher Zustande und Funktionen. I. Von JuliusSpringer, Berlin.

HULTEN MA, HONEYMAN MM, MAYNE AJ & MJTARLOW 1987. Homozygosity in piebald trait.Journal of Medical Genetics 24: 568-71.

JEFFERSON TA 1990. Sexual dimorphism and de-velopment of external features in Dall's porpoisePhocoenoides dam. Fishery Bulletin 88: 119-32.

KASUY A T 1981. Identification manual of dolphinsand porpoises in the Japanese waters. ResearchDivision, Japan Fisheries Agency: 41 pp. In Ja-

panese. [Not seen].KASUYA T, MIYASHITA T & F KASAMATSU 1988.

Estud. Oceanol. 12, 199352

VAN WAEREBEEK K & JC REYES. In press. Theinteraction of small cetaceans and Peruvian fish-eries, catch statistics 1988-1989 and analysis oftrends. In Mortality of Cetaceans in passive Fish-ing Nets and Traps, International Whaling Com-

mission (Special Issue).WALKER WA, GOODRICH KR, LEATHERWOOD

S & RK STROUD 1984. Population biology andecology of the Pacific white-sided dolphin, Lage-norhynchus obliquidens, in the northeasternPacific. Part II: biology and geographical varia-tion. Adm. Report LJ-84-34C, NMFS/SWFC, LaJolla, California, 39 pp.

WALKER WA, LEATHERWOOD S, GOODRICHKR, PERRIN WF & RK STROUD 1986. Geo-graphical variation and biology of the Pacific whi-

te-side dolphin, Lagenorhynchus obliquidens,in the north-eastern Pacific. In Research onDolphins. MM Bryden and Harrison (eds.). Ox-ford University Press, Oxford, pp 441-465.

WATERHOUSE GR 1838. The Voyage of H.M.S.Beagle during the years 1832-1836. Mammalia,part II. London, 96 pp.

WATSON L 1981. Whales of the World. Hutchinson& Co., London, 302 pp.

WEBBER M 1987. A comparison of dusky and Paci-

fic white-sided dolphins (Genus Lagenorhyn-chus): morphology and distribution. M.Sc. the-sis, San Francisco State University, 102 pp.

WEBBER M & S LEATHERWOOD 1990. Duskydolphin, Lagenorhynchus obscurus. In Wha-les and dolphins. A.R. Martin (ed.). SalamanderBooks, London, pp. 154-155.

WONNACOTT TH & RJ WONNACOTT 1969. Intro-ductory Statistics. Fifth Edition 1990, John Wiley& Sons, New York, 711 pp.

WORSIG B 1991. Cooperative foraging strategies:an essay on dolphins and us. Whalewatcher

25(1): 3-6.WORSIG B & TA JEFFERSON 1990 Methods of

photo-identification for small cetaceans. Re-ports of the International Whaling Commis-sion, Special Issue 12: 43-52.

WORSIG B, KIECKHEFER TR, JEFFERSON TA1990. Visual displays for communication in ceta-ceans. In Sensory Abilities of Cetaceans. J. Tho-mas & R. Kastelein (eds.), Plenum Press, New

York, pp. 545-559.WORSIG B & M WORSIG 1978. Day and night of the

dolphin. Natural History 88(3): 60-67.WORSIG B, WORSIG M & F CIPRIANO 1989. Dol-

phins in different worlds. Oceanus 32(1): 71-75.YANEZ P 1948. Vertebrados marinos chilenos I:

mamiferos marinos. Revista de Biologia Mari-na (Chile) 1 (2): 103-23.

the spinner dolphin Stene//a longirostris in theeastern Pacific and implications for conserva-tion. Fishery Bulletin, 89: 411-428.

PERRIN WF & SB REILLY 1984. Reproductive pa-rameters of dolphins and small whales of thefamily Delphinidae. Reports of the Internatio-nal Whaling Commission, Special Issue 6:

97-133.PERRIN WF, SLOAN PA & JR HENDERSON 1979.

Taxonomic status of the "southwestern stocks" ofspinner dolphin Stenel/a longirostris and spotteddolphin S. attenuata Reports of the Internatio-nal Whaling Commission 29: 175-184.

QUAYLE L 1988. Dolphins and Porpoises. GalleryBooks, New York, 144 pp.

READ AJ, VAN WAEREBEEK K, REYES JC,MCKINNON JS & LC LEHMAN 1988. The ex-ploitation of small cetaceans in coastal Peru.Biological Conservation 46: 53-70.

RIDGWAY SH 1976. Statement at Hearings beforethe Subcommittee on Fisheries and Wildlife andthe Environment, U.S. House of RepresentativesMerchant Marine and Fisheries Committee, May4, 1976 [not seen].

SERGEANT DE 1962a. The biology of the pilotwhale or pothead whale Globicepha/a melaena(Traill) in Newfoundland waters. Bulletin Fishe-ries Research Board of Canada 132: 1-84.

SERGEANT DE 1962b. On the external charactersof the blackfish or pilot whales (genus Globicep-ha/a). Journal of Mammalogy 32(3): 395-413.

SLlJPER EJ 1962. Whales: Basic books, 511 pp.STSC, Inc. 1989. STATGRAPHICS [software]. Sta-

tistical Graphics System by Statistical GraphicsCorporation, Rockville, USA.

SUNDFOR H 1939. A pedigree of skin-spotting inman - 42 piebalds in a Norwegian family. Jour-nal of Heredity 30: 67-77.

VAN WAEREBEEK K 1992. Population identity andgeneral biology of the dusky dolphin Lage-norhynchus obscurus (Gray, 1828) in theSoutheast Pacific. Ph.D. thesis, University ofAmsterdam. 160 pp.

VAN WAEREBEEK K 1993. Geographic variationand sexual dimorphism in the skull of the duskydolphin Lagenorhynchus obscurus (Gray,1828). Fishery Bulletin 91(4): 754-774.

VAN WAEREBEEK K & AJ READ. In press Repro-duction of dusky dolphins Lagenorhynchusobscurus from coastal Peru. Journal of Mam-malogy.

VAN WAEREBEEK K & JC REYES. 1990. Catch ofsmall cetaceans at Pucusana port, central Peru,during 1987. Biological Conservation 51 (1):15-22.

Van Waerebeek. External Features of the dusky dolphin 53

YONEKURA M, MATSUI S & T KASUYA 1980. Onthe external characters of Globicephala ma-crorhynchus off Taiji, Pacific coast of Japan.

Scientific Reports of the Whales ResearchInstitute 32: 67-95

ZAR JH 1974. Biostatistical Analysis. Second Ed.1984. Prentice-Hall Inc., New Jersey, 718 pp.

~

FECHAACEPTACION: 15 noviembre 1993