HERBERT MAIER · Wenden wir uns dem größten Werk der Ausstellung, dem Monumental-Gemälde...

Transcript of HERBERT MAIER · Wenden wir uns dem größten Werk der Ausstellung, dem Monumental-Gemälde...

-

HERBERT MAIER

EDITION BRAUS

-

Herbert Maier

-

EDITION BRAUS ISBN: 978-3-89466-309-4

Veröffentlichungen des Morat-Instituts | Herausgegeben von Franz Armin Morat und Wolfram Morath-Vogel | Band VII

-

HERBERT MAIERMorat-Institut für Kunst und Kunstwissenschaft, Freiburg i. Br.

-

Inhalt | Contents

Franz Armin Morat Time in painting 6

Zeit im Bild 7

Rüdiger Heinze Here time becomes space, or Spherical time the space of colour light and sound

The paintings of Herbert Maier 10

Zum Raum wird hier die Zeit oder Die Kugelzeit im Farblichtklangraum

Über die Malkunst Herbert Maiers 11

Malerei 1990– 2004 | Paintings 1990–2004 30

Window-Paintings 46

Naturzeit-Gebautezeit | Naturaltime-Constructedtime 64

aus Mexiko | from Mexico 90

Eva M. Morat › Minimal handholds ‹

The sketchbooks of Herbert Maier 108

› Minimale Haltegriffe ‹

Zu den Skizzenbüchern von Herbert Maier 109

Peter-Cornell Richter › What you see is what you see ‹

The photographs of Herbert Maier 130

› What you see is what you see ‹

Zu den Fotografien von Herbert Maier 131

Biografie | Biography 151

Ausstellungsverzeichnis | Index of exhibitions 152

Bibliografie | Bibliography 156

Autoren | Authors 158

Impressum | Imprint 160

-

6

Franz Armin Morat Time in painting

τοῦτο γάρ ἐστιν ὀ χρόνος,ἀριϑµὸς ϰινήσεως ϰατὰ τὸπρότερον ϰαὶ ὕστερον.

For more than twenty years and more systematically than most of his fellow artists, HerbertMaier has thought about the problem of time in painting; and he has not only thought aboutit, but has also acted upon his thoughts accordingly, both in artistic and in technical terms. His interest was, of course, never in a historical conception of time (for example: "Goya and his time"),but in a systematic or physical conception, as is alsoexpressed in the definition by Aristotle above.1)

Largely simultaneously, Gottfried Boehm conducted his studies on aesthetics which are documented in the Herbert Maier catalogue of 2004 (published by the Morat Institute, VolumeIV, p. 8).

An awareness of this problem – or at least the beginnings of such an awareness – already existedmuch longer ago: in his « Salon de 1763 » Diderot writes about some of Chardin’s still lifes: «Approchez-vous, tout se brouille, s‘aplatit et disparaît: éloignez-vous tout se crée et se reproduit.»

In 1862, on seeing Chardin’s Basket of Strawberries, the Goncourt brothers wrote of the «merveilleuseopération d‘optique entre la toile et le spectateur, dans l‘espace». This «merveilleuse opération»can only take place and be experienced in the course of time; where or when else?!

-

7

Franz Armin Morat Zeit im Bild

τοῦτο γάρ ἐστιν ὀ χρόνος,ἀριϑµὸς ϰινήσεως ϰατὰ τὸπρότερον ϰαὶ ὕστερον.

Konsequenter als die meisten seiner Kollegen hat der Maler Herbert Maier schon seit mehr alszwanzig Jahren über das Problem der Zeit in der Malerei nachgedacht; und er hat nicht nur nach-gedacht, sondern auch entsprechend künstlerisch und handwerklich gehandelt. Dabei ging es ihm selbstverständlich nie um einen historischen Zeitbegriff (Beispiel: „Goya und seine Zeit“), sondernum einen systematischen oder physikalischen, so wie dies auch in der oben stehenden Definitiondes Aristoteles zum Ausdruck kommt.1)

Zeitlich weitgehend parallel entstanden die kunstwissenschaftlichen Untersuchungen Gottfried Boehms, wie sie im Herbert Maier-Katalog von 2004 dokumentiert sind (Veröffentlichungen desMorat-Instituts, Band IV, S. 8).

Ein Bewusstsein für diese Problematik hat jedoch – zumindest in Ansätzen – schon wesentlich früher existiert: In seinem « Salon de 1763 » schreibt Diderot über einige Stillleben Chardins: «Approchez-vous, tout se brouille, s‘aplatit et disparaît: éloignez-vous tout se crée et se reproduit.»

1862 werden die Brüder Goncourt anlässlich von Chardins Erdbeerkorb von der « merveilleuse opéra tion d‘optique entre la toile et le spectateur, dans l‘espace» sprechen. Diese «merveilleuseopération» kann nur im Zeitfluss stattfinden und erlebt werden; wo oder wann denn sonst?!

-

8

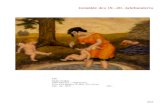

Let us turn to the largest work of the exhibition, the monumental painting ( 240x990 cm, 3 panels,see page 107) "Speicher - Grosses Mexiko". Considered in terms of content, it depicts part ofthe base of the wall of an Aztec temple, viewed close up. Herbert Maier most certainly did notintend to paint an architectural picture. The crucial aim of his work on this painting is toenable the openminded and observant viewer to have tangible experiences which areonly possible in the process of looking when it is experienced over a period of time. Thisexperiencing of time does not happen by means of some trick – to that extent it is no« trompe-l‘œil » painting – but as a result of the eye’s natural ability literally to jump back andforth between the convex and the concave. The time that the eye requires to switch fromthe surface to the space makes it possible to experience time. (Almost as a by-product, oneis convincingly made to understand once again how obsolete the antagonism betweenabstraction and representationalism has always been.)

The painting technique that makes such experiments and experience possible is that of oil glaze painting of Jan van Eyck. In his incredibly persistent approach to his work, Herbert Maierhas further developed and perfected this technique, which cost him not least a tremendousamount of time. The work of applying seventy to eighty glazes to this painting extended overmore than an entire year. What is revealed under natural light conditions is that the light captured in this way has a constitutive character. The change in the mode of appearance of apainting with changing illumination is of fundamental significance. This, too, is an importantaspect of Herbert Maier’s work. There is no one mode of appearance of a painting, even thoughreproductions may suggest this. Our perception is subject to constant change.

1) Martin Heidegger: "Time is this; namely something counted in connection with motion, as encountered in the horizon

of earlier and later." (Being and Time, p. 421)

Rainer Marten: "For that is time: that which is counted or the countable number of motions with regard to earlier and

later." (memo to the author, July 24th 2009)

-

9

Wenden wir uns dem größten Werk der Ausstellung, dem Monumental-Gemälde „Speicher - Grosses Mexiko“ (dreiteilig, 240x990 cm, siehe Abbildung S. 107), zu: Inhaltlich betrachtet han-delt es sich um die Sockel-Zone der Wand eines Azteken-Tempels – aus großer Nähe betrachtet.Ganz gewiss hat Herbert Maier kein Architektur-Bild beabsichtigt. Entscheidendes Ziel seiner Arbeitan diesem Bild ist es, dem aufgeschlossenen und aufmerksamen Betrachter anschauliche Erfah-rungen zu ermöglichen, die nur in dem im Zeitfluss erlebbaren Prozess der Anschauung möglichwerden. Die Bewusstwerdung von Zeit geschieht nicht durch einen Trick – insofern ist es keine« trompe-l‘œil »-Malerei – sondern durch die natürliche Fähigkeit des Auges, zwischen konvex undkonkav buchstäblich hin und her springen zu können. Die Zeitspanne, die das Auge benötigt, umvon der Fläche in den Raum zu wechseln, macht Zeit erlebbar. (Quasi als Nebenprodukt wird einweiteres Mal über zeugend nachvollziehbar, wie obsolet der Antagonismus von Abstraktion und Ge-genständlichkeit eigent lich von allem Anfang an gewesen ist.)

Die maltechnische Voraussetzung für das Möglichwerden solcher Experimente und Erfahrungen istdie Lasurmalerei Jan van Eycks. Herbert Maier hat in seiner unerhört insistierenden Arbeitsweise die-se Technik weiter entwickelt und perfektioniert, was nicht zuletzt auch einen unerhörten Zeitauf-wand voraussetzt. Die Arbeit an den siebzig bis achtzig Lasuren dieses Bildes hat sich über mehrals ein ganzes Jahr hingezogen. Dass das dabei gespeicherte Licht einen konstitutiven Charakterhat, offenbart sich unter den Bedingungen des natürlichen Lichtes. Der Wandel der Erscheinungs-weise eines Bildes in wechselnder Beleuchtung ist von substantieller Bedeutung. Auch dies ist einwichtiger Aspekt im Werk von Herbert Maier. Es gibt nicht die eine Erscheinungsweise eines Bildes,auch wenn dies Reproduktionen suggerieren mögen. Die Wahrnehmung ist einem ständigen Wan-del unterzogen.

1) Martin Heidegger: „Das nämlich ist die Zeit, das Gezählte an der im Horizont des Früher und Später begegnenden

Bewegung.“ (Sein und Zeit, S. 421)

Rainer Marten: „Denn das ist die Zeit: Gezählte bzw. zählbare Zahl der Bewegung in Anbetracht des Früher und Später.“

(Mitteilung an den Autor vom 24. Juli 2009)

-

10

"The steps, the edging at the corners, the recess of the steps, the slightly overhanging"tablero" (vertical wall panel) – all these elements are shadow-casters that serve to three-dimensionalize the pyramid appreciably in the sun. Without them, the monuments wouldappear flat in the light of day."

Herbert Maier noted down this observation while visiting the Maya ruins of Tikal in Guatemala on 28Januar 2008. Even a stranger to the place can imagine without difficulty the rhythmic alterna tion bet-ween the glaring reflections from the stone steps and the dark, hard shadows cast by the very same stepsthat Maier then preserved in his sketchbook in drawings and watercolours. The stark contrasts, the shapes of the steps, the regular rhythms made a lasting impression and subsequently spawned the firstwatercolours in which this light-dark motif appeared, with parallel stripes criss-crossing the pictures atregular intervals (see p. 46/47, 118, 119, 121), and later oil paintings with the same theme, titled "ausMexiko" [from Mexico] that are the last of Herbert Maier’s cycles of works for the time being.No painting would seem more suitable for novices in the contemplation of his works than "Speicher /ausMexiko" (see page 97). It vividly unites three fundamental principles in Maier’s painting by showing eachof them at their clearest. The large square format is characterised by horizontal stripes that are oc ca-sionally interrupted by much lighter vertical rod-like colour fields. At first sight, one believes one seesthe following: broad, ochre-coloured areas encounter small, almost white areas – the painting as an ir-regularly patterned wall and a section of a whole. At a second glance, however, the viewer hesitates.One’s eyes wander, jump back and forth, think they recognise shadows here and light there, falling fromthe right, the back here, the front there. The third glance finally reveals the areas of colour to be a

Rüdiger Heinze Here time becomes space, or Spherical time the space of colour light and soundThe paintings of Herbert Maier

-

11

„Die Stufen, an den Ecken die Einkragungen, das Zurücksetzen der Stufen, das leichte Vor-springen der „tablero“ (vertikales Mauerband), all diese Elemente sind Schattenwerferund plastifizieren die Pyramide wesentlich in der Sonne – ohne sie würden die Monu-mente im Tageslicht flach erscheinen.“

Diese Beobachtung notierte Herbert Maier am 28. Januar 2008 an der Maya-Ruinenstätte von Tikal in Guatemala. Selbst der Ortsfremde kann sich unschwer jenen rhythmischen Wechsel zwischengleißenden Steintreppen-Reflektionen und dunklen, harten Steintreppen-Schlagschatten vorstellen,wie sie Maier dann auch in sein Skizzenbuch zeichnete und aquarellierte. Die starken Kontraste, dieStufenformen, die regelmäßigen Takte wirkten nach, und in der Folge entstanden zunächst Aquarelle,die das Hell-Dunkel-Motiv in parallelen Streifen und Bändern intervallartig durchspielten (siehe Abbildungen S. 46 /47, 118, 119, 121), später Ölgemälde zu diesem Thema, das heute unter dem Titel „aus Mexiko“ den vorläufigen Schlusspunkt der Werkzyklen Herbert Maiers setzt.Für Novizen in der Betrachtung seiner Gemälde, scheint kaum ein Bild so geeignet zu sein wie „Speicher / aus Mexiko“ (siehe Abbildung S. 97). Anschaulich vereint es drei wesentliche Prinzipiender Malerei Maiers, indem es sie in ihrer jeweils klarsten Ausprägung zeigt. Das quadratische Groß-format bestimmen horizontale Streifen, die gelegentlich durchbrochen sind von einigen deutlichhelleren, senkrechten Stabfeldern. Der erste Blick hält für richtig: breite, ockerfarbene Flächen tref-fen auf kleine, nahezu weiße Flächen – das Bild als unregelmäßig gemusterte Wand und als Aus-schnitt einer Totalen. Auf den zweiten Blick jedoch stutzt der Betrachter. Die Augen wandern,springen hin und her, glauben hier Schatten zu erkennen, dort ein anscheinend von rechts einfal-

Rüdiger Heinze Zum Raum wird hier die Zeit oder Die Kugelzeit im Farblichtklangraum Über die Malkunst Herbert Maiers

-

12

structure of solid bodies. The horizontal stripes take on a three-dimensionality, bulge outwards, look –in a derivation from the pyramid-step motif – like stacked-up bars, whose front ends shine in the brightsunlight. In this way, the "seeing time" that Maier demands on principle for his paintings brings abouta basic broadening of perception. To achieve this, he now mainly uses glaze painting, the technique ofthe Netherlandish "ars nova" first developed systematically in the early 15th century, which used layers of transparent glaze both to suggest greater three-dimensionality and to create an interplay ofcolours that was full of nuances due to the inner light thus achieved. Oil as a binder and turpentine asa thinner made – and, once again today, make – this possible. We will be returning to the use of glaze in Maier’s art in greater detail later; for the moment, it only remains to be said that once thestructure and effect of "Speicher /aus Mexiko" (see p. 97) has been observed and recognised, an essential part of its creator’s aesthetic endeavour has been understood.

"Why would the old cultures – the Indians, Persians, Egyptians, Greeks, Mayas – have otherwise erected gates in the wilderness without city walls or buildings if they had notknown that whoever passes through them seems more important at that moment andthat the image framed by the boundaries of the gate is seen more intensively, more immediately by whoever looks through it."

(Sketchbook /Mexiko-New York 2008.3)

If one considers "Speicher / aus Mexiko", which – like all of Maier’s paintings since 1989 – is forvarious reasons subsumed to the general title "Speicher" [Reservoir], as the primary form of the"Mexico" paintings, "Speicher /aus Mexiko", painted in shades of blue and brown (see. p. 101 and,even more so, "Speicher / aus Mexiko”, illustrated on pages 103, 104 and 105) prove to be ad-vanced, more complex variants in the cycle. Firstly, the step-like areas mesh together and, secondly, the light-coloured areas seem to push their way into the picture from both the left and theright, which places the accent even more strongly on dynamism and structuring. For that reason, Maier also briefly considered calling the paintings in this series "Fugue" – as a specific reference tothe related art of music. Because the light-coloured areas, which seem to be illuminated, but in fact– even in half-light – glow from within, are propelled into the picture from two sides, the impressioncreated in several passages of the painting is one of conflicting perspectives, or even of divergingsolid object constructions. If one allows one’s eye to wander, then the steps become wedged together, twisting in space, creating stereometric perspectives that negate reality. It would be shabby, however, to consign Maier’s work and artistic endeavour to the magic realm of optical illu-sion and picture puzzle. His thinking as a painter goes deeper, stating that pure painting withoutdepth perspective – derived, it is true, from representationalism, but then casting it off – overcomestwo-dimensionality and makes the leap into the next higher dimension. Thus the field of colour attains the status of a solid body, the area the status of space, the pigment the status of light. However, even though this is a central aspect of Maier’s painting, it does not stop there.

"Painting provides the means of colour and shape and therefore, as a painter, I want toheighten these very means to the utmost. I would feel it inadequate, were I not to acceptthe challenge of painting (i.e. of colour and shape) to its full and greatest extent."

(Sketchbook / Freiburg 2008.4)

-

13

lendes Licht, hier ein Hinten, dort ein Vorn. Der dritte Blick schließlich offenbart die Flächen als einKörpergefüge. Die horizontalen Streifen gewinnen an Plastizität, werfen sich auf, erscheinen – ab-geleitet vom Pyramiden stufen-Motiv – als gestapelte Riegel, deren Kopfenden im hellen Sonnen-licht erstrahlen. So bewirkt die „Sehzeit“, die Maier prinzipiell für seine Gemälde einfordert, eineprinzipiell erweiterte Wahrnehmung, für die er mittlerweile prinzipiell die Lasur-Malerei einsetzt, je-ne systematisch zu Beginn des 15. Jahrhunderts entwickelte Technik der altniederländischen „Arsnova“, die anhand sich überlagernder, transparenter Farbschichten sowohl verstärkte Plastizitätsuggeriert als auch eine innere Leuchtkraft nuanciertesten Farbspiels ins Leben ruft. Öl als Binde-mittel, Terpentinöl als Verflüssigungsmittel machten – und machen es heute erneuert – möglich.Von der Lasur in Maiers Kunst wird noch ausführlich die Rede sein; zunächst bleibt festzuhalten: Ist„Speicher / aus Mexiko“ (Abbildung S. 97) in seinem Aufbau und in seiner Wirkweise beobachtetund erkannt, ist schon ein wesentlicher Teil des ästhetischen Strebens seines Urhebers verstanden.

„Warum sonst hätten die alten Kulturen – Inder, Perser, Ägypter, Griechen, Mayas – Toreohne Stadtmauern oder Gebäude in die Wildnis stellen sollen, wenn sie nicht gewusst hät-ten, dass, wer hindurch geht, im Augenblick bedeutender, dem, der hindurchschaut, dasBild innerhalb der Torgrenzen intensiver, dichter erscheint.“

(Skizzenbuch /Mexiko-New York 2008.3)

Tritt „Speicher / aus Mexiko“, das – wie alle Gemälde Maiers seit 1989 – aus mehre ren Gründenunter dem Generaltitel „Speicher“ zu subsumieren ist, als eine Art Urbild der „Mexiko“-Malereienauf, so erweist sich das in Blaubraun gehaltene „Speicher / aus Mexiko“ (siehe Abbildung S. 101und mehr noch „Speicher / aus Mexiko“ in den Abbildungen auf Seite 103, 104 und 105) als fort-geschrittene, komplexere Variante im Zyklus. Zum einen treffen die Stufenflächen versetzt auf-einander, zum zweiten scheinen sich die hellen Flächen sowohl von links als auch von rechts insBild zu schieben, das derart verstärkt einen Akzent auf Dynamik und Fügung setzt. Deshalbüberlegte Maier auch eine Zeitlang, die Bilder aus dieser Serie als „Fuge“ zu bezeichnen – durchausals Verweis auf die Kunstschwester Musik. Indem sich aber die wie beleuchtet erscheinenden,in Wirklichkeit – selbst in der Dämmerung – von innen herausstrahlenden Flächen von zwei Seitenins Bild drängen, entsteht in etlichen Gemälde-Passagen der Eindruck sich widersprechenderPerspektiven, ja auseinanderstrebender Körperkonstruktionen. Schweift der Blick, ver keilensich die Stufen, krümmen sich im Raum, erwecken stereometrische Ansichten, die die Wirklichkeitnegieren. Doch wäre es billig, Maiers Arbeit und Kunstwollen dem Zauberreich der Augen-täuschung und des Vexierbildes zuzuordnen. Sein malerisches Denken stößt tiefer: Reine Malereiohne Tiefenperspektive – abgeleitet zwar aus der Gegenständlichkeit, doch diese abstreifend – über-winde die Ebene und schaffe den Sprung in die nächst höhere Dimension. Das Farbfeld erreicheden Rang des Körpers, die Fläche den Rang des Raumes, das Pigment den Rang des Lichts. Dochauch bei diesem Kernaspekt bleibt die Malerei Maiers nicht stehen.

„Malerei bietet die Mittel Farbe und Form und deshalb will ich als Maler eben diese Mit-tel zur vollen Steigerung bringen. Es wäre mir ein Ungenügen, die Herausforderung derMalerei (also der Farbe und Form) nicht in vollem und höchstem Maße anzunehmen.“

(Skizzenbuch / Freiburg 2008.4)

-

14

Before, but also at the same time as the "Mexico" paintings, Maier produced a group of worksin his Freiburg studio entitled "Naturzeit - Gebautezeit" [Naturaltime - Constructedtime] whichalludes to organic, natural growth and anorganic, artificial, cultural artefacts. In terms of motifs, this series of paintings could be seen to be derived on the one hand from chromosomepatterns or from the rhythmic (light-dark) structures of birch bark, or, on the other hand, fromscene settings – be they in the studio or on the stage. However, these remain merely hints whichcan be supported, it is true, by pictures in Maier’s photograph archive and by our own expe riencesin general observation, but which do not have the slightest intention of mimetic representa tion.Taken literally, they would indicate an all too simple path into the real world. Rather, the cyclehas its source – analogously to the "Mexico" paintings – in the processing in many variants ofthe shapes that the artist has seen, gathered and stored – hence the choice of "Reservoir" asthe title given to all of Maier’s works. For his works, the distinction between abstract and figu-ra tive /representational makes no sense. Nonetheless, in the large-format "Speicher / Naturzeit- Gebautezeit" (see p. 84), flanked by counterparts in dark red (see p. 83) and dark blue (seep. 85), we look upon a kind of cinematic or theatrical situation: an observation slit – like a shut-ter, with a wide angle – opens up in the lower section of the painting, revealing semi-crystal -line, semi-organic shapes in dynamic motion. The shutters appear to be semi-transparent, likecoloured glass, and suggest that behind them, too, the ordered flight of the shapes continues.And yet, the more closely the written word may approximate the situation and visual percep- tion, the more the picture eludes any description. Neither the staggering of the depth of all the elements in the space created, nor the illumination can be explained: a wealth of meaning beyond language. The shapes and solid objects penetrate each other, front and back remainopen, levels imagined to be seen become lost, the clusters of light falling from above, whichglow as long as they are still behind the transparent glass, appear darkened once they enter theopening: shadow light.The dynamic and the static, before and after, the transparent and the veiled, light and shade areall held in suspension in contradictory, confusing and exciting simultaneity. Just like in well-execu-ted watercolours, whose delicately coloured watery layers Herbert Maier later compresses in hispaintings, here, too, the effect of an aura is produced. This light, this scene-like character, almostdemands that the “Speicher” paintings from the years 2002/2003, which were seen in connec tionwith "curtains" (see p. 41), undergo a re-examination and reinterpretation: it may be that they donot refer to materiality in the narrower meaning of the word, but to the reflection of light fallingor raining down upon a stage that opens out into space in an imaginary way. If one were lookingfor a subtitle for this « coup de théâtre », then "Play of light without a plot" might suggest itself.However, both the old and the new interpretation could easily be applied: Light curtain, Light sculp-ture. The ideas formulated by Leon Battista Alberti in his treatise on painting, written in 1435 /1436on the threshold to the modern age, can also be applied to the work of Herbert Maier: "We dividepainting into three parts… In the first place, when we look at a thing, we say that this object occu pies a space… When we look again, we recognise that several surfaces of the object seen fittogether; and here, the artist, when describing their positioning, would say that he is making a com-position. Finally, we observe more clearly the colours and the qualities of the surfaces, whose variations are received from the light, and therefore we can apply term this part of the represen-tation in painting the reception of light."

-

15

Vor, aber auch gleichzeitig mit den „Mexiko“-Gemälden entstand im Freiburger Atelier die Werk-gruppe „Naturzeit - Gebautezeit“, die anspielt auf organisches, natürliches Wachsen und anor-ganisches, künstliches, kulturelles Menschenschaffen. Motivisch könnte sich die Bildserie ableiteneinerseits aus Chromosomen-Darstellungen oder aus den rhythmischen (Hell-Dunkel-) Strukturenvon Birkenrinde, andererseits aus dem Szenischen – sei es das Studio oder die Bühne. Dies bleibenallerdings lediglich Fingerzeige, die sich zwar durch Aufnahmen im Foto-Archiv Maiers sowie durchallgemeine Betrachtungserfahrungen stützen lassen, die aber nicht die geringsten Absichten zumimetischer Darstellung nach sich ziehen. Wörtlich genommen würden sie einen allzu simplenWeg in die konkrete Welt weisen. Viel mehr speist sich der Zyklus – analog zu den „Mexiko“-Bil-dern – aus der variantenreichen Verarbeitung gesammelter, gespeicherter Formerscheinungen –auch deshalb der Titel „Speicher“ über der Gesamtheit der Werke Maiers. Für sein Schaffen ergibtdie Unterscheidung von abstrakt und figürlich/gegenständlich keinen Sinn. Gleichwohl blicken wirbei dem Großformat „Speicher /Naturzeit -Gebautezeit“ (siehe Abbildung S. 84), dem Pendantsin dunklem Rot (siehe Abbildung S. 83) und dunklem Blau (siehe Abbildung S. 85) zur Seite stehen,auf eine Art von filmischer oder theatralischer Situation: blendenartig, breitwandig, öffnet sich imunteren Bildbereich ein Sehschlitz, der die Sicht freigibt auf halb kristalline, halb organische Formenin dynamisiertem Bewegungsfluss. Die Blenden erscheinen halbtransparent wie Farbgläser und las-sen vermuten, dass sich auch hinter ihnen der geordnete Flug der Formen fortsetzt. Doch je näherdas geschriebene Wort der Situation und optischen Wahrnehmung kommen möchte, desto wei-ter entfernt sich das Bild von der Beschreibung. Weder ist die Tiefenstaffelung aller Elemente imRaum zu klären, noch die Lichtverhältnisse: Bedeutungsfülle jenseits von Sprache. Die Formen undKörper durchdringen sich, Vorne und Hinten bleiben offen, augengedachte Ebenen verlieren sich,die von oben herabfallenden Lichtbündel, glühend noch hinter dem transparenten Glas, wirken imoffenen Sehspalt wie verdunkelt: Schattenschein.In widersprüchlicher, verwirrender, erregender Gleichzeitigkeit werden Dynamik und Statik, Vorherund Nachher, Transparenz und Verhüllung, Licht und Schatten in der Schwebe gehalten. Wie in gelun genen Aquarellen, aus deren zart getönten Wasserschichten Herbert Maier malerische Ver-dichtungserfahrung zieht, wirkt auch hier ein Fluidum. Diese Lichtverhältnisse, diese Sze nen haftig-keit verlangen fast, jene „Speicher“- Bilder aus den Jahren 2002/2003, die mit „Vorhängen“ inVerbindung gebracht wurden (siehe Abbildung S. 41), einer Neubetrachtung und Umdeutung zuunterziehen: Womöglich verweisen sie nicht auf Stofflichkeit in engerem Wortsinn, sondern auf denWiderschein fallenden oder regnenden Lichts über einer Bühnenfläche, die sich zum Raum imagi-när weitet. Wollte man einen Untertitel für diesen « coup de théâtre » finden, so böte sich an: „Sze-nische Lichtaktion ohne Handlung“. Doch können ohne weiteres auch die ältere wie die neuereDeutung zur Deckung gebracht werden: Lichtvorhang, Lichtskulptur. In übertragenem Sinn giltauch für die Arbeit Herbert Maiers, was Leon Battista Alberti 1435 /1436 an der Schwelle zur Neu-zeit in seiner Abhandlung über die Malerei formulierte: „Man unterteilt die Malkunst in drei Teile…Erstens, wenn wir etwas erblicken, sagen wir, dass dieser Gegenstand einen Ort beansprucht…Bei erneuter Betrachtung erkennen wir dann, dass mehrere Oberflächen des gesehenen Körperszusammentreffen; und hier wird der Maler, indem er ihre Orte bezeichnet, sagen, er mache eineKomposition. Zuletzt unterscheiden wir noch genauer die Farben und die Eigenschaften der Ober-flächen, deren Verschiedenheit durch die Lichtverhältnisse entsteht, und deshalb können wir die-sen Teil der Abbildung passend Lichteinfall nennen.“

-

16

"Painting is not an abstracted product, but the product formed by the act of painting ofthe essential outer world which has passed through the channel of the inner world."

(Skizzenbuch /Crete 2007.2)

But now let us turn our attention to a third group of works: the "Window Paintings", the basis forwhose motif was laid during a US scholarship at the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in 2004. Taking as their starting point the view of, into and behind a lattice window, Herbert Maier produceda cycle – again first in watercolours (see p. 46 /47), then in oil – which, to put it briefly, combines theartistic product of his examination of what could be described as a materialised motif-forma tion inwoodcut and the sensory impression of a field of vision defined by the grid of a lattice window. Here, too, the view of something real was once again the starting point for a creation of images thatgoes beyond naturalistic reproduction. However, the reality that the artist reduced to a concentrateof form originated not only in the tangible world, like the grid motif, which has always fascinated Maier, but also in the sensory impression, the appearance and the imagination. It was in 1993 that Herbert Maier visited the catacombs of San Cennaro in Naples and experienced the dark ness of an unilluminated recess as a blackness that physically existed, as a body, as a thing. Thisexperience was also the starting point for numerous woodcuts with centred shapes with a compact,dark, heavy force of attraction – and the term "emptybody" (Leerekörper) in Herbert Maier’s per-ception and work. "Empty bodies" for him are impressions of empty space that in certain lights ap-pear to be tangible, material. Frames, lattices and "empty bodies" thus became motifs that appearedin the "Window Paintings" which were to lead to key works with regard to his connection of spaceand time in painting. If one looks at the striking blocks of colour in the "Speicher" painting that heproduced over a period of three years (see p. 43), if one also looks at that painting’s further deve-lopment in "Großer Speicher" (2003 /2004): a grid of rectangles characterises the landscape format,with a width of nearly seven metres (see p. 45), that can be "read" both horizontally and vertically– as as result of the graphically notated, strictly structured layers. If one concentrates one’s eye onone of the three centrally located glazed colour fields in ochre, blue and red – a characteristic, interacting, broken colour chord in Maier’s more recent work – one finds one’s eye being drawn into a spatial depth – as if a compartment has opened in the canvass. If one widens one’s angle of vision again, however, one comes up against the frame and is directed back to the entire surfacewhich the viewer’s "seeing time" divides into intervals. Space and surface, moment of seeiing andduration of observation correlate with one another. The painting seems both to rest in itself and todevelop rhythmically. It gives the impression of a succession of compartments, spaces and blocks ofcolour of semingly differently depths, as well as of a structured unified colour field. Maier comparedthis type of painting with marquetry: flat, contrasting materials inlaid in wood.

Interlude I. One of the most enigmatic moments in Wagner’s stage-consecrating festival play"Parsifal" – a work full of enigma – occurs in the finale of the first act. Not only is no answer givenhere to Parsifal’s question "Who is the Grail?" ("That cannot be spoken"), but following that, the"pure fool" Parsifal also makes a curious statement: "I hardly tread, yet far I seem to have come"– whereupon, to the strains of the choir, Gurnemanz, the historiographer of the Knights of the Grailas it were, explains: "You see, my son, here time becomes space". Thus, long before Albert Einstein and his Theory of Relativity, Richard Wagner had a premonition in his poetry, whose

-

17

„Malerei ist das nicht abstrahierte, sondern aus Malerei gebaute Erzeugnis von essentiel-ler Außenwelt durch den Weg der Innenwelt.“

(Skizzenbuch /Kreta 2007.2)

Doch sei hier noch eine dritte Werkgruppe näherer Betrachtung unterzogen: die „Window-Paintings“, deren motivische Basis während eines US-Stipendiums in der Josef und Anni AlbersFoundation 2004 gelegt wurde. Ausgehend vom Blick auf, in und hinter ein Sprossenfenster, ent-stand – wieder erst im Aquarell (siehe Abbildung S. 46 /47), dann in Öl – ein Zyklus, der abgekürztdargestellt den künstlerischen Ertrag von Herbert Maiers Auseinandersetzung mit einer gleichsammaterialisierten Motiv-Durchbildung im Holzschnitt und dem Sinneseindruck eines fensterspros-sengerasterten Blickfelds kombiniert. Auch hier war wieder die Sicht auf etwas Reales der Aus-gangspunkt für eine Bilderfindung jenseits naturalistischer Wiedergabe. Die zum Formkonzentratgeronnene Realität entstammte allerdings nicht nur der greifbaren Welt, wie das Gitter-Motiv, dasMaier von jeher fasziniert, sondern auch dem Sinneseindruck, dem Augenschein, der Phantasie. Eswar 1993, als Herbert Maier die Kata komben von San Cennaro in Neapel besichtigte und dort dasDunkel einer unausgeleuchteten Nische als physisch existente Schwärze, als Körper, als ein Dingempfand. Auch aus diesem Erlebnis heraus entstanden zahlreiche Holzschnitte mit zentrierten For-men von kompakter, tiefer, schwerer Anziehungskraft – und der Begriff des „Leerekörpers“ in Wahr-nehmung und Schaffen Herbert Maiers. „Leerekörper“ sind ihm Eindrücke des leeren Raums, derunter spezifischen Lichtverhältnissen wie greifbar, wie dinghaft wirkt. So flossen Rahmen, Sprossenund „Leere körper“ motivisch in die „Window-Paintings“ ein, die zu Schlüsselwerken bezüglich sei-ner malerischen Verknüpfung von Raum und Zeit führen sollten. Man sehe auf die prägnanten Farb-blöcke in jenem „Speicher“-Bild, das über drei Jahre hinweg entstand (siehe Abbildung S. 43), mansehe zudem auf dessen Fortentwicklung „Großer Speicher“ von 2003 /2004: Ein Raster von Recht-ecken bestimmt das nahezu sieben Meter breite Querformat (siehe Abbildung S. 45), das sowohl ho-rizontal als auch vertikal „gelesen“ werden kann – als Folge graphisch notierter, streng gegliederterSchichten. Konzentriert sich dabei der Blick auf eines der drei mittig gesetzten Lasur-Farbfelder inOcker, Blau und Rot – ein charakteristischer, interagierender, gebrochener Farb-Akkord in Maiers jün-gerem Werk –, so wird er in eine räumliche Tiefe gesogen – als ob sich ein Fach öffnete in der Lein-wand. Weitet der Blick sich aber wieder, so stößt er gegen die Rahmen und wird zurückgelenkt aufdie Gesamtfläche, die die Sehzeit des Betrachters in Takte unterteilt. Raum und Fläche korrelierenmiteinander, Seh-Moment und Beobachtungsdauer. Das Bild ruht sowohl stehend in sich, als es sichrhythmisiert auch ent wickelt. Es wirkt als Folge anscheinend unterschiedlich tiefer Farbfächer, Farb-räume, Farbblöcke ebenso wie als strukturierte Farbfeld-Übersicht. Maier hat für diesen Bildtypus denVergleich mit einer Intarsienarbeit geprägt: plan in Holz eingelegte kontrastierende Materialien.

Interludium I. Einer der rätselhaftesten Augenblicke des voller Rätsel steckenden Bühnenweih-festpiels „Parsifal“ findet sich im Finale des 1.Aktes. Nicht nur wird hier eine Antwort verweigertauf Parsifals Frage „Wer ist der Gral?“ („Das sagt sich nicht“), im Folgenden gelangt der „reine Tor“Parsifal auch zu der merkwürdigen Aussage: „Ich schreite kaum, doch wähn’ ich mich schon weit“ –worauf Gurnemanz, gleichsam der Geschichtsschreiber der Gralsritter, zu Choralklängen erklärt:„Du sieh’st, mein Sohn, zum Raum wird hier die Zeit“. Weit vor Albert Einstein also und dessen Rela tivitätstheorien erahnte Richard Wagner in seiner Dichtung, die das „(mit)fühlende Wissen“

-

18

theme was "(com)passionate knowledge", of the relationship between the dimensions of "space"and "time" which later, in the 20th century, were to have such an enormous influence on the arts – all the way to Herbert Maier’s examination of the four dimensions "line", "area", "space"and "time". While the reference to Wagner’s "Parsifal" only opens up a parallel to Maier’s workto the extent of an after-thought, one other late-Romantic composer in particular clearly deservesto be brought into connection with his "Window Paintings" on the grounds of musical architectureand structure: Anton Bruckner. The orchestration that develop into a monolithic block in the ope-ning and closing movements of his symphonies which – interspersed with rests or, rather, pausingchord columns – progress as if in a broad current, build up a comparable relationship between audible structure (vertical) and duration of experience (horizontal). Walls of sound, charged withenergy, that move towards the listener, resound like pent-up space and periodic process in equalmea sure. These walls of sound in Bruckner’s works correspond to the structured flood of colourand light in Maier’s.

Two further "Speicher" paintings from the years 2004 and 2005 (see p. 54, 55) present an echoof the "window" motif and are reminiscent of graphic musical notation. The layered linearity instructs the eye in intensified parallel reading; the embedded strips of colour appear like lines ona contemporary musical score with visual accentuation of two groups of parts respectively. Thedensity of events and information on the canvass increases; the lines which have to be taken in simultaneously are disrupted (rest), staggered (alternation of parts), at times also composedpolypho nically. Out of this two-dimensional representation of sound arise specific sound spacesin the depth perspective. If these two "Speicher"paintings were indeed musical scores in pictureform, the thought of a polyphonic piece would then suggest itself on account of design andstructure. In fact, there exists a small-format "Fugue" by Josef Albers (Kunstmuseum Basel) pain-ted in 1925 in which the interweaving of time, rhythm, contrasting parts and tonal colours arevisualised. What strikes one immediately is the fact that Albers, with whom Herbert Maier is, ofcourse, also related with regard to the interaction of colour, material and space, executed his "Fugue" on frosted glass with molten paint, thus also using transparent, shimmering, nuancedcolour effects. Here, as there, the aim was the same: to explore the fourth dimension artisticallyin a succession of constantly ex tended physical findings concerning the phenomenon of the in-terdependence of space and time.To return to the painting of Herbert Maier, everything that has been described up to now seemsto be based solely upon a rational, scientific, theoretical artistic approach. However, the "WindowPaintings" series in particular is an example showing that his art in its final state is far more crea-ti vely impulsive than the intellectual principles noted thus far would suggest. The two "Speicher"paintings previously mentioned, for example, reveal beyond their constructive content not only anemotional inner structure through violent strokes of the brush, but also, upon closer study, an un-usual production process which is ultimately constitutive and effective. As a result of his coveringindividual layers of glaze with adhesive tape, different levels of representation intersect on higherand lower planes. This is joined in the "Window Paintings" by a third element: Maier performs adeclination of the window-frame shapes upon which the paintings are based, deconstructing them("Speicher /New York – Bamako I" 2004 /2005, see p. 61), bending them to form arcs that are reminiscent of Gothic tracery, bringing to mind ribbed vaults ("Speicher", 2005, see p. 56, 57, 59).

-

19

zum Thema hat, jene Beziehung zwischen den Größen „Raum“ und „Zeit“, die dann, im 20. Jahr-hundert, auf die Bildenden Künste enormen Einfluss haben sollte – bis hin zu Herbert Maiers Aus-einandersetzung mit den vier Dimensionen „Gerade“, „Fläche“, „Raum“ und „Zeit“. Eröffnet sichdurch den Verweis auf Wagners „Parsifal“ jedoch lediglich in hintergründig-gedanklicher Hinsichteine Parallele zum Werk Maiers, so steht insbesondere mit dessen „Window-Paintings“ ein weite-rer Komponist der Spätromantik anhand seiner musikalischen Architektonik und Faktur geradezuoffen in Verbindung: Anton Bruckner. Dessen sich in den Symphonie-Ecksätzen blockhaft entwi-ckelnden „Orgelregistraturen“, die – durchsetzt von Pausen beziehungsweise innehaltenden Ak-kordsäulen – als ein breiter Strom fortlaufen, bauen ein vergleichbares Verhältnis zwischenHörgliederung (vertikal) und Erlebnisdauer (horizontal) auf. Klangwände, die energetisch auf denHörer zufahren, ertönen als gestauter Raum und als periodischer Prozess gleichermaßen. DiesenKlangwänden Bruckners entspricht die strukturierte Farb- und Lichtflut Maiers.

Einen Widerhall des „Window“-Motivs mit Anklängen an graphische musikalische Notationen füh-ren zwei weitere „Speicher“-Bilder aus den Jahren 2004 und 2005 vor (siehe Abbildungen S. 54,55). Geschichtete Linearität leitet das Auge zu intensiviert-paralleler Lesearbeit an; die eingelager-ten Farbbahnen erscheinen wie Zeilen einer zeitgenössischen Partitur mit optischer Hervorhebungjeweils zweier Stimmgruppen. Ereignis- und Informationsdichte nehmen auf der Leinwand zu; diesimultan aufzufassenden Zeilen sind durchbrochen (Pause), versetzt (Stimmablösung), mitunterauch vielstimmig komponiert. Aus der Klangfläche lösen sich hier wie dort zwei spezifische Klang-räume in Tiefenstaffelung. Wären die beiden „Speicher“ tatsächlich ins Bild gesetzte Klangschrif-ten, dann läge auf Grund von Anlage und Aufbau der Gedanke an ein polyphones Stück nahe. In der Tat gibt es aus dem Jahr 1925 die kleinformatige „Fuge“ von Josef Albers (Kunstmuseum Basel), in der Verflechtungen von Takt, Rhythmus, kontrastierenden Stimmen sowie Tonfarben vi-sualisiert sind. Ins Auge springt gleichzeitig, dass Albers, mit dem Herbert Maier ja auch in Bezug auf„Farbraumkörper“ in Verbindung steht, seine „Fuge“ einst auf Milchglas mit aufgeschmolzener Far-be ausführte, also ebenfalls transparente, schimmernde, farbnuancenbetonte Wirkungen nutzte.Hier wie dort gilt des Weiteren: malerische Erforschung der vierten Dimension in Folge permanenterweiterter physikalischer Erkenntnisse zum Phänomen der Abhängigkeit von Raum und Zeit.Zurück zur Malerei Herbert Maiers. Alles, was bisher beschrieben, scheint allein auf rationalen, wis-senschaftlichen, erkenntnistheoretischen künstlerischen Ansatzpunkten zu beruhen. Doch istgerade die Serie der „Window-Paintings“ ein Beispiel dafür, dass sich seine Kunst im abschließen-den Zustand als schöpferisch weit impulsiver erweist, als es die bislang vermerkten gedanklichenPrinzipien vermuten lassen. So offenbaren die zwei erwähnten „Speicher“-Bilder aus der Serie„Window-Paintings“ jenseits ihrer konstruktiven Faktur nicht nur eine bewegte Binnenstrukturdurch gestisch heftige Pinselschwünge, sondern bei genauem Betrachten auch ein außergewöhn-liches, im Ergebnis konstitutiv-wirkungsvolles Herstellungsverfahren. In Folge passagenweisen Ab-deckens einzelner Lasurschichten durch Klebestreifen verschränken sich tiefer und höher gelegeneDarstellungsebenen vielschichtig. Hinzu kommt in den „Window - Paintings“ ein Drittes: Maierdekliniert die zu Grunde liegende Fensterrahmen-Form durch, bricht sie dekonstruktiv auf(„Speicher /New York -Bamako I“ 2004 /2005, siehe Abbildung S. 61), ja beugt sie in des Wortesdoppelter Bedeutung zu Bögen, die an gotisches Maßwerk, an ein Kreuzrippengewölbe denkenlassen (siehe Abbildungen S. 56, 57, 59).

-

20

"I want a space that is based in the (colour) area, that is not static, but does not exist with out the active temporality of the viewer’s perception."

(Sketchbook / Freiburg 2008.4)

Looking back into the past, to 1994 and the appearance of the first publication on Herbert Maier,this autodidact who persistently taught himself theory and practice, the first work shown, and alsothe oldest work shown, was the grisaille painting "Wachsende Verdichtung / Raumzeichnung"produced in 1989 /1990 (illustration I in text p. 20). At the time of the work’s genesis, Maier’s crea-tive path could not, of course, be foreseen – and yet: in retrospect one has to see the starting pointfor his work in that very oil-and-steel assembly. At the point at which one would stop "reading",if it were the page of a book, i.e. at the bottom right-hand corner, we find the focal pointupon which this work converges. A delicate, grid-like structure, reminscent of the residue of cutor punched metal, gains contours, contrast and three-dimensionality, then to grow out of the pic ture physically in the form of the steel on which it stands on the floor. The fragments drawnbecome an object, or rather something "material", as Maier puts it – or read backwards: a three-dimensional sculpture is reduced to a two-dimensional surface. Painting and sculpture are mu tuallydependent, and some of Herbert Maier’s general themes become obvious from this early stage:grid, fragment, objectification, the elevation of area into space, flat representation of solid objects.Although he was still painting with paste paints then, his tendency towards superimposed layersis already recognisable in "Wachsende Verdichtung / Raumzeichnung" – as also in "Speicher / fürMorandi" (1993, see p. 33), where the shapes of three upturned containers begin to take onmassive form. That a two-dimensional shape can at the same time suggest a solid body, and alsospace, emptiness, content, gap, background – this dialectic artistic experience and perceptionwas one that appeared in Maier’s work in the early 90s – probably at its most striking and in itspurest form in the wall-filling one-off woodcut by the name of "Grosses Holz". Mainly in blackand white, notations from sketchbooks have been worked into shapes which arch upwards outof the plane or seem to be buried in the paper depths. The printed ink takes on a physical presence, forms itself into a block, stretches itself to create the illusion of a body. Who would notbe reminded of the heavy elegance of Richard Serras’ steel walls on seeing the page in woodcut by the name of "Das Grosse Holz" (see p. 21) that separates the white (above) andthe black (below) in a bent, slightly corroded border (see p. 23)? Yet again, Maier ventures intoan imagined space. His woodcuts on the one hand and his experiments with glazed and heavilylayered water colour painting in the early 90s on the other, were finally to lead to a synthesisof these two (perceptual) experien ces after the year 2000. We know this today from his oil glazepaintings. But before that, as he now admits, he came to a dead-end.

"Nothingness, or emptiness, or the transparent – call it what you will – we can nevergrasp it, and yet it is just as present as the things, the objects, the bodies that we cantouch."

(Sketchbook /Crete 2001.2)

This dead-end, with its ultimately cathartic effect, appeared in 1999 when Herbert Maierwanted to paint a picture that was differentiated in terms of colour, but should not encourage

Speicher / Wachsende Verdichtung | 1989 /1990

Öl auf Leinwand, Stahl | 225x140x60 cm

-

21

„Ich will einen Raum, der sich aus der (Farb-)Fläche begründet, der nicht statisch da ist, son-dern ohne die aktive Zeitlichkeit der Wahrnehmung des Betrachters nicht vorhanden ist.“

(Skizzenbuch / Freiburg 2008.4)

Ein Blick in die Vergangenheit. Als 1994 die erste Publikation über Herbert Maier, diesen sich selbstin Theorie und Praxis beharrlich schulenden Autodidakten erschien, da galt die erste Abbildung, dieälteste gezeigte Arbeit, dem Grisaille-Bildwerk „Wachsende Verdichtung /Raumzeichnung“ von1989/1990 (siehe Abbildung S. 20). Natürlich war zum Zeitpunkt seiner Entstehung der Schaffens-weg Maiers nicht abzusehen gewesen – und doch: Im Nachhinein muss man einen Ausgangspunktseiner Arbeit in genau dieser Öl-Stahl-Assemblage sehen. Dort, wo man sie zu „lesen“ aufhören wür-de, wenn es sich um eine Buchseite handelte, dort am unteren rechten Rand liegt der Schwerpunktder sich in diese Richtung verdichtenden Arbeit. Eine zarte gitterartige Struktur, die an Ausschnei-de- oder Stanzreste erinnert, gewinnt Kontur, Kontrast und Plastizität, um dann regel recht hand-greiflich in Stahl aus dem Bild zu wachsen und dieses am Boden abzustützen. Die gezeich netenFragmente werden zum Ding, beziehungsweise „dinghaft“, wie Maier es ausdrückt – oder rückwärtsgelesen: eine Plastik gerinnt zur Fläche. Gemälde und Skulptur bedingen einander, und offensicht-lich werden schon früh einige Generalthemen Herbert Maiers: Gitter, Fragment, Verdinglichung,räumliches Aufladen von Fläche, plane Darstellung von Körpern. Obgleich er damals noch mit pas-tosen Farben malte, ist in „Wachsende Verdichtung /Raumzeichnung“ bereits auch sein Hang zuübereinander gelegten Schichten zu erkennen – wie auch in „Speicher / für Morandi“ von 1993 (sie-he Abbildung S. 33), da die Formen dreier auf den Kopf gestellter Gefäße beginnen, massige Ge-stalt anzunehmen. Dass eine Flächenform zugleich einen Körper suggerieren kann, wie auch Raum,Leere, Inhalt, Aussparung, Fond – diese dialektische Malerfahrung und Sehsicht trat bei Maier zu Be-ginn der 90-er Jahre ins Bild, am Prägnantesten und Reinsten wohl in den wandfüllenden Holz-schnitt-Unikaten namens „Grosses Holz“. Vornehmlich in Schwarz-weiß sind hier Notate ausSkizzenbüchern weiterverarbeitet zu Formgebilden, die sich aus der Fläche herauszuwölben oder indie Papiertiefe einzugraben scheinen. Die Druckfarbe nimmt physische Präsenz an, baut sich block-haft auf, dehnt sich zur Körper-Illusion. Wem würde nicht die schwere Eleganz von Richard SerrasStahlwänden in den Sinn kommen, wenn er jenes Blatt aus „Das Grosse Holz“ (siehe Abbildung S.21) betrachtet, das Weiß (oben) und Schwarz (unten) durch eine gekrümmte, leicht korrodierendeGrenze trennt? Einmal mehr stößt Maier in den imaginierten Raum vor. Seine Holzschnitte einerseits,seine Erprobung stark lasierender und stark geschichteter Aquarellmalerei zu Beginn der 90-er Jah-re andererseits (siehe Abbildung S. 23), sollten schließlich nach dem Jahr 2000 zu einer Synthese bei-der (Wahrnehmungs-)Erfahrungen führen. Wir kennen diese heute aus seiner Öl-Lasurmalerei. Dochzuvor geriet er, wie er mittlerweile bekennt, in eine Sackgasse.

„Das Nichts oder das Leere oder das Transparente oder wie immer wir es nennen wollen,wir fassen es nie, und doch ist es präsent wie das Fassbare, die Dinge und Gegenstände,die Körper.“

(Skizzenbuch /Kreta 2001.2)

Diese Sackgasse mit letztlich kathartischer Wirkung tat sich 1999 auf, als sich Herbert Maier ab-verlangen wollte, ein farblich differenziertes Bild zu malen, das nicht zu einer Assoziation von Land-

aus der Serie: „Das Grosse Holz“ | 1997

Holzschnitt | 248x159 cm

-

22

any associations with landscape. It was to be "pure", avoiding any suggestion of panorama or horizon, but without appearing to be evenly applied, not following the aesthetics of colourfield painting, as Maier did not want to lose the pure form of painting itself and its nuances. However, even in the slightest colour contrasts he could not see a solution to the problem – only failure, the colour area remaind landscaped (see p. 37). What also concerned him at that time was a second question. Although he had already experimented with time and the flow ofpainting and seeing in a nearly twenty-metre-wide painted frieze (see p. 30 /31) in 1990, he stillwondered how the factor of "time" could be captured once more on canvass as "pure" pain-ting at the turn of the 21st century – i.e. without regard for such substitutes as symbols, signs,metaphor, allegory, etc. Although he would not state this so clearly, this naturally excluded for him the further pursuit of the approaches found in conceptual art that had been applied to the theme of "time" in the decades before. One recalls here Roman Opalka (born 1931), On Kawara (born 1933) and Hanne Darboven (born 1941).

A visit to the Louvre in 2000, during a scholarship at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris, wasdecisive in prompting Maier to overcome both problems in artistic terms by searching and circling.Francisco de Zurbarán’s painting "The Exposition of the Body of Saint Bonaventura", like many representations of Saint Hieronymus, contains a sumptuous crimson cardinal’s mitre that stands outin terms of proportion and colour. Thereupon Maier took for himself this mitre as a single motif –and with it the long-established technique of oil glaze painting. With this technique he began toput his idea to the test: would the crimson be able have an effect and endure as a colour in itself,even if it were largely robbed of its representational content (see p. 22). And glaze painting proved – time-consuming as it was – to be a means to an end: without using the suggestive toolsof perspective and the interplay of light and shade, Maier extracted a physical quality of the crimson from the two-dimensional colour plane which also drew its light value from within itself – "lustro da per sé", as Giorgio Vasari once described it. It is not without reason that, etymologicallyspeaking, glaze and glass are sisters.

"In view of all the ugliness that is paraded, what interests me is the concept of the beauti- ful – and how beauty can momentarily flash up in a picture without being fashionable andeager to please."

(Sketchbook / Freiburg 2008.4)

Since Paris, since that encounter with the "The Exposition of the Body of Saint Bonaventura",Herbert Maier has been developing his glaze painting technique. His formerly palimpsest-likelayers of paste paint have now given way to superimposed, translucent skins and films. The glazes increase the immaterial, light-induced element in the picture’s presence several times over;they act outwardly towards the viewer and create depth in the area of colour in equal measure.The glazes contain secrets, and also imponderables, as their interaction cannot be totally planned, cannot be totally recapitulated in a state of completion, i.e. in retrospect. Maier, whoapplies up to 70 glazes to one painting, still speaks today, despite years of experience, of "con-trolled coincidence", particularly in the inner structures of the paintings. His large-scale pain-tings are produced within a minimum time frame of eight months, during which the balance

Speicher | 2000 /2001

Öl auf Leinwand | 33x41 cm | Privatbesitz

-

23

schaft verleiten sollte. Es musste „rein“ sein, jedweden Anklang an Panorama oder Horizontbildungunterlaufen, aber eben auch nicht wie gleichmäßig angestrichen wirken, nicht der Farbfeldästhetiknachkommen, da Maier das Malen selbst und dessen Nuancen nicht verlieren wollte. Doch selbst beigeringsten Farbkontrasten sah er keine Lösung des Problems, nur ein Scheitern, die Farbfläche bliebdem Landschaftlichen verpflichtet (siehe Abbildung S. 37). Ihn bewegte damals aber noch eine zwei-te Fragestellung. Obgleich er sich schon 1990 in einem nahezu zwanzig Meter breiten Bilderfries (siehe Abbildung S. 30 /31) mit der Zeit sowie dem Fluss des Malens und des Sehens auseinander-gesetzt hatte, trieb ihn weiter um, wie der Faktor „Zeit“ in der Wende zum 21. Jahrhundert auf Lein-wand als abermals „reine“ Malerei festgehalten werden könne – also ungeachtet solcher Substitutewie Symbol, Zeichen, Metapher, Allego rie etc. Ohne dass er es beim Namen nennen würde, schieddamit auf natürliche Weise auch die Fortführung jener Spielarten konzeptueller Kunst aus, wie sie sichdem Thema „Zeit“ in den Jahrzehnten zuvor zu gewandt hatten. Erinnert sei hier an Roman Opalka(geboren 1931), On Kawara (geboren 1933), und Hanne Darboven (geboren 1941).

Ein Besuch des Louvre während eines Stipendiums an der Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris gab Maier dann im Jahr 2000 den entscheidenden Anstoß, durch Suchen und Umkreisen den beidenProblemen künstlerisch Herr zu werden. Francisco de Zurbaráns Gemälde „Die Aufbahrung des Leichnams des Heiligen Bonaventura“ enthält ebenso wie viele Darstellungen des HeiligenHieronymus einen proportional und farblich stark betonten Kardinalshut in kostbarem Purpurrot. Die-ses Hutes nun versicherte sich Maier als eines Einzelmotivs – und ebenso der althergebrachten Lasur-Ölmalerei. In dieser Technik begann er die Probe aufs Exempel: Ob das Purpurrot als Farbe in sichwirken und bestehen könne, auch wenn sie ihres bildnerischen Inhalts weitgehend beraubt wird (sie-he Abbildung S. 22). Und die Lasurmalerei erwies sich – Zeit einfordernd – als ein Mittel zum Zweck:Ohne dass er die suggestiven Werkzeuge von Perspektivenbildung und Licht- / Schattenführungeneinsetzte, gewann Maier aus der Farbfläche heraus eine Körperhaftigkeit des Purpurrots, die zudemihren Lichtwert aus sich selbst heraus bezog – „lustro da per sé“, wie Giorgio Vasari es einst be-zeichnet hatte. Nicht ohne Grund sind, etymologisch betrachtet, Lasur und Glasur zwei Schwestern.

„Nach all dem herausgekehrt Hässlichen interessiert mich gerade deshalb der Begriff desSchönen – und wie Schönheit in einem Bild gegenwärtig aufzuleuchten vermag, ohnegeschmäcklerisch und anbiedernd zu sein.“

(Skizzenbuch / Freiburg 2008.4)

Seit Paris nun, seit der Begegnung mit der „Aufbahrung des Leichnams des Heiligen Bonaventura“,schreitet Herbert Maier in der Lasurmalerei fort. Übereinandergelegten, durchscheinenden Farb-häuten und Farbfolien sind seine zuvor pastosen, palimpsesthaften Farbschichtungen gewichen.Die Lasuren erhöhen den immateriellen, lichtgelenkten Anteil an der Bildpräsenz um ein Mehrfaches;sie wirken gleichermaßen nach vorne, auf den Betrachter zu, wie sie Tiefe in der Farbfläche erzeu-gen. Die Lasuren bergen Geheimnisse, auch Unwägbarkeiten, indem ihr Zusammenwirken nichtrestlos geplant, im Stadium der Vollendung, also im Nachhinein, nicht restlos rekapituliert werdenkann. Maier, der bis zu 70 Lasuren auf ein Bild aufträgt, spricht auch noch nach Jahren der Erfah-rung von „gesteuertem Zufall“, vor allem in den Binnenstrukturen der Gemälde. Seine großen Bil-der entstehen in einem Minimum-Zeitrahmen von acht Monaten, in denen immer wieder neu die

aus der Serie: „Gedächtnis der Dinge / Schichtkörper“ | 1994

Aquarell | 200x125 cm

-

24

between shade and light is readjusted again and again – in order to gain depth and three-dimensionality on the one hand and radiance on the other. From time to time Maier draws a veilof colour over the entire format; from time to time he contravenes academic theory – by glazinglight over dark, or when he integrates passages of dirty grey tones, so that the same colourglows all the more translucent elsewhere. As Maier puts it succinctly: "All the things you aren’tsupposed to do were done by the old masters too." In addition, in his work using oil glaze tech-nique, he is reviving things which had to a great extent been lost: madder red lightened with white produces a colour that is at the least an awkward, if not shameless, pink; madder red, however, if thinned with turpentine, is transformed into a light, gentle purple that – like all itslight values – is brought to life by incidental and unusually reflected light. Covering all of this,however, is a sealing oil-resin glaze without which the depth of light could not be achieved. (It is worth noting, incidentally, that due to the thin nature of the glazes, the large paintings sometimes have to be laid on the floor of the studio for glazing using an extended brush in thedecisive phases of their genesis and that – due to the health hazard of working with turpentine– their creator wears and has to wear a breathing mask while he paints.)

"Reservoir [Speicher]: implies an overlapping, or rather a penetration of different timesand places, experiences and events – from the past, but also from the future."

(Sketchbook / Freiburg 2008.4)

If one were to attempt to sum up Herbert Maier’s work over the past nine years – that near-decade in the focus of his exhibition at the Morat Institute for Art and Art Science in 2009 andat the centre of this illustrated volume which accompanies it – in one lexical sentence, one wouldhave to express that his wish as an artist consists in using the means of oil glazing to store themathematical and physical dimensions as an image mechanism of conflicting forces, with the aimof expanding our perceptions. It is to these conflicts in particular, these contradictions of as many forces as possible immanent within the pictures that Maier attaches the greatest impor-tance – thus creating a further contradiction: he wishes to reveal both the conflict and the tensely interlinked unity of the opposing parts at the same time – polarity in intrinsic commonality.Maier strives towards nothing other than the complex search, which he repeatedly undertakesanew, for a comprehensive dialectic world view, a visualisation of his understanding of the world,a practical search led by reflection to find the interfaces between the grounds of the picture,between area and space, between emptiness and body, surface and depth, the static and the dynamic, light and shade, colour and form, transparency and density, rest and continuum. Andwith the last-mentioned functions, in which, once again, the one is inconceivable without theother, we finally come to the dimension in Maier’s painting that stands above the conflict and –paradoxically – at the same time preserves it: Time. Looked upon on a simple representative andinterpretative level, his "Speicher" paintings concentrate on the memory and processing of motifs that haves been experienced and on the technical heritage of the art of the Old Masters.On a higher level, they inform us of a carefully progressing painting process that demands an increasingly meditative viewing process: just as the time for composing leads to examination during the time for listening and the time for writing require a time for reading, so too doesHerbert Maier insist, after a deliberate time for painting, upon a circumspect and emphatically

-

25

Balance zwischen Abschattierung und Aufhellung austariert wird – um einerseits Tiefe und Räum-lichkeit zu gewinnen, andererseits Eigenglanz. Mitunter zieht Maier einen Farbschleier über das ge-samte Format; mitunter verstößt er gegen die akademischen Lehren – eben, wenn er hell überdunkel lasiert, oder wenn er passagenweise schmutzige Grautöne integriert, auf dass an andererStelle dieselbe Farbe umso strahlender transluzid leuchte. Maier lapidar: „Die ganzen Sachen, dieman nicht machen sollte, haben auch die Alten gemacht.“ Darüber hinaus reanimiert er anhand derLasur-Technik auch weitgehend verloren Gegangenes: Krapplack, aufgehellt durch Weiß, ergibt einzumindest heikles, wenn nicht schamloses Pink; Krapplack aber, verdünnt durch Terpentinöl, ver-wandelt sich in ein helles, sanftes Purpur, das – wie all seine Valeurs – vom einfallenden und au-ßerordentlich reflektierten Licht zum Leben erweckt wird. Über allem aber liegt ein beschließenderÖlharzlasurglanz, der ein Tiefenlicht erst ermöglicht. (Dass auf Grund der dünnflüssigen Lasurenzumal die großen Bilder in ihren entscheidenden Phasen auf dem ebenen Atelierboden mit Hilfe ver-längerter Pinsel entstehen und entstehen müssen, dass ihr Urheber des Weiteren – auf Grund desgesundheitsgefährdenden Terpentinöls – beim Malen eine Atemschutzmaske trägt und tragen muss,dies sei hier nur am Rande vermerkt.)

„Speicher: impliziert eine Überlagerung, mehr noch eine Durchdringung verschiedenerZeiten und Orte, Erfahrungen und Ereignisse – von der Vergangenheit aber auch von derZukunft her.“

(Skizzenbuch / Freiburg 2008.4)

Wollte man Herbert Maiers Arbeit der zurückliegenden neun Jahre – jene knappe Dekade im Zen-trum seiner Überblicksschau des Morat-Instituts für Kunst und Kunstwissenschaft 2009 und im Zen-trum des dazugehörigen, hier vorliegenden Bildbandes –, wollte man also diese Arbeit in einemlexikalischen Satz zusammenfassen, so müsste die Sprache davon sein, dass sein künstlerischer Wil-le darin besteht, mit den Mitteln der Öllasur und dem Ziel der Wahrnehmungsverbreiterung die ma-thematisch-physikalischen Dimensionen als einen Bild-Mechanismus von widerstreitenden Kräftenzu speichern. Insbesondere auf diese Widerstreite, ja bildimmanenten Widersprüche möglichst vie-ler Kräfte legt Maier dabei höchsten Wert – derart einen weiteren Widerspruch erzeugend: Offenzu legen sind für ihn gleichzeitig Widerstreit sowie die spannungsvoll-verzahnte Einheit der Wider-parts: Polarität bei wesenhafter Zusammengehörigkeit. Nichts anderes als die komplex sich gestal-tende Suche nach einem umfassenden dialektischen Weltbild strebt Maier in immer neuen Anläufenan, eine Anschaulichkeit seines Weltverständnisses, eine der Reflexion folgende praktische Suchenach den Schnittstellen zwischen den Bildgründen, zwischen Fläche und Raum, zwischen Leere undKörper, Oberfläche und Tiefe, Statik und Dynamik, Licht und Schatten, Farbe und Form, Transparenzund Dichte, Einhalt und Kontinuum. Und mit den letztgenannten Funktionen, bei denen wiederumdas eine ohne das andere nicht zu denken ist, kommt schließlich jene Größe in Maiers Malerei, dieden Widerstreit überwölbt und – in paradoxer Weise – gleichsam haltbar macht: die Zeit. Auf ein-facherer Darstellungs- und Deutungsebene konzentrieren seine „Speicher“-Bilder die Erinnerungund Verarbeitung erlebter Motivik sowie das handwerkliche Erbe altmeisterlicher Kunst. Auf höhe-rer Ebene künden sie von einem behutsam fortschreitenden Malprozess, der einen sich zunehmendversenkenden Betrachtungsprozess verlangt: Wie Komponierzeit eine Auseinandersetzung in derHörzeit nach sich zieht und Schreibzeit eine Lesezeit, so besteht Herbert Maier nach bedachtsamer

-

26

slow time for seeing. The picture does not save the viewer the effort of thinking; it is only com-plete once it has arrived by way of his eye in his brain. On the highest level, however, he demandsof himself that he integrates the future in artistic presentiments, visions and utopias – not in anoracle-like sense, but rather in the physical-philosophical sense: How would it be if, once spacehad reached its maximum point of expansion, time were reversed as space collapsed? Then theeffect would precede the cause, the "conditio sine qua non". Maier explores nothing other, there fore, than a "spherical form of time", nothing other than the association of past (memoryof shapes, processed motifs), paper-thin present (seeing time) and future (tentative vision, returnof the past), in order to acquire them for his painting. That this intellectual desire in its most out-standing examples quite naturally goes hand in hand with creating vibrant and delicate presenceas the supreme dictate in painting is experienced by visual people as a great moment of auric intensity. These are powerful pictures, declares the art historian and philosopher Gottfried Boehm,that "metabolise reality", that "make something of reality visible to us that we would never dis-cover without them."1) However, the fact that it requires an outstretched antenna on the part ofthe viewer keeps Maier’s work from being embraced universally.

Interlude II. It is of great benefit for all who study Herbert Maier’s painting to listen to thosecompositions which set milestones in musical history around the year of his birth in 1960. Thisapplies in particular to John Cage (born 1912), Bernd Alois Zimmermann (born 1918) and György Ligeti (born 1923), but also to the painter Yves Klein (born 1928), who between 1947and 1961 developed a form of sound pattern that ultimately transformed his monochromepaintings into acoustic resonance. It can come as no surprise that all the artists mentioned were also philosophically preoccupied with time, temporal perception and space. An exampleof this is Ligeti’s "Continuum" for harpsichord (1968) that within a maximum of four minutesof "prestissimo" compresses two racing voices into oscillating resonance and Ligeti’s orchestralcomposition "Atmosphères" (1961) which attempts to do away with the traditional sequenceof sound and silence (rest) in a continuous acoustic presence. John Cage, on the other hand,composed what was probably – in contrast to his silent "4’33" (three "Tacet" movements forany instrument or combination of instruments) – the first piece in musical history without a fixed time frame. The decisive aspect of the graphically notated "Variation IV" (1963) is that optional sound sources have to emanate from predetermined places in the room. Bernd AloisZimmermann deserves particular attention. He too is an artist who posed himself aestheticquestions in order to arrive at concrete artistic solutions. Last but not least, in his opera "DieSoldaten" (1957 – 1965, based on a play by Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz), he underpinned the"spherical form of time" which he propagated – i.e. the unity of past, present and future bymeans of the layered use of quotations from different times and origin like a montage. Zimmermann wrote in the conviction that diverse perceptions of time could be reflected musically like objectively measured and subjectively felt time. In his last works up to 1970 heeven laid several time lines on top of each other ("Photoptosis", 1968). In the mean time, YvesKlein’s "Symphonie Monoton Silence" for 32 musicians and 20 singers, in this version proba-bly notated by the composer Pierre Henry, is hardly ever performed. For years, Yves Klein experimented with the idea of allowing a sound such as the D-major chord to float in a roomfor several minutes, followed by prolonged silence as an echo. In 1960, the "Symphonie

-

27

Malzeit auf umsichtige, betont langsame Sehzeit. Das Bild erspart dem Betrachter das Denken nicht,vollendet ist es erst in seinem, dem Auge angeschlossenen Gehirn. Auf höchster Ebene jedoch er-hebt er den Anspruch an sich selbst, in bildnerischen Ahnungen, Visionen und Utopien die Zukunfteinzubinden – also nicht in einem orakelhaften Sinne, viel mehr in einem physikalisch-philosophi-schen Sinne: Wie etwa, wenn nach der größten Ausdehnung des Weltraums die Zeit sich umkehr-te im Zusammenstürzen des Raumes? Dann träten Wirkungen vor der Ursache, vor der „conditiosine qua non“ ein. Nichts anderes also als eine „Kugelgestalt der Zeit“, nichts anderes als die Ver-knüpfung von Vergangenheit (Formerinnerung, verarbeitete Motivik), hauchdünner Gegenwart(Sehzeit) und Zukunft (tastende Vision, Wiederkehr von Vergangenheit) erkundet Maier, um sie fürdie Malerei zu gewinnen. Dass dieses gedankliche Verlangen in den schönsten Beispielen wie selbst-verständlich Hand in Hand geht mit einer vibrierend-delikaten Bildpräsenz als oberstem Malgebot,ist von Augenmenschen als großer Moment auratischer Dringlichkeit zu erfahren. Dies sind starkeBilder, erklärt der Kunsthistoriker und Philosoph Gottfried Boehm, die „Stoffwechsel mit der Wirk-lichkeit betreiben“, die „uns an der Wirklichkeit etwas sichtbar machen, das wir ohne sie nie er-führen.“1) Indem es allerdings dafür auch einer ausgerichteten „Antenne“ des Betrachters bedarf,wird Maiers Arbeit vor der Umarmung allenthalben bewahrt.

Interludium II. Es ist für alle, die sich mit Herbert Maiers Malerei beschäftigen, ein Gewinn, jeneKompositionen zu hören, die rund um seinen Jahrgang 1960 musikgeschichtliche Wegmarken setz-ten. Insbesondere ist dabei an John Cage (geb. 1912), Bernd Alois Zimmermann (geb. 1918) undGyörgy Ligeti (geb. 1923) zu denken, aber auch an den Maler Yves Klein (geb. 1928), der zwischen1947 und 1961 ein tönendes Klangbild weiterentwickelte, das letztlich seine monochromen Gemäl-de transformierte zu akustischer Resonanz. Es kann nicht erstaunen, dass sich alle genannten Künst-ler mit Zeit, Zeitwahrnehmung und Raum auch philosophisch beschäftigten. Hingewiesen sei hierauf Ligetis „Continuum“ für Cembalo (1968), das binnen maximal vier „Prestissimo“-Minuten ra-sende Zweistimmigkeit zu oszillierender Klangfläche verdichtet sowie auf Ligetis Orchesterkomposi-tion „Atmosphères“ (1961), die die tradierte Abfolge von Ton und Stille (Pause) aufzuheben sucht ineinem akustisch andauerndem Stehen. John Cage wiederum komponierte – in Kontrast zu seinemlautlosen „4’33“ (drei „Tacet“-Sätze für beliebige Besetzung) – das wohl erste Stück der Musikge-schichte ohne verbindlichen Zeitrahmen. Der entscheidende Aspekt der graphisch notierten „Varia-tion IV“ (1963) ist, dass beliebige Klangquellen an vorbestimmten Plätzen im Raum zu erklingenhaben. Besondere Aufmerksamkeit sei aber auf Bernd Alois Zimmermann gelenkt, auch er ein Künst-ler, der selbstgestellte ästhetische Fragen nutzte, um zu konkreten künstlerischen Lösungen zu ge-langen. Nicht zuletzt in seiner Oper „Die Soldaten“ (1957–1965, nach Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz)unterfütterte er die von ihm propagierte „Kugelgestalt der Zeit“ – also die Einheit von Vergangen-heit, Gegenwart und Zukunft durch montageartig geschichtete Verwendung von Zita ten un terschied-licher Zeiten und Herkunft. Zimmermann schrieb in der Überzeugung, diverse Zeitwahrneh mungenwie objektiv gemessene und subjektiv empfundene Zeit musikalisch widerspiegeln zu können. In sei-nen letzten Werken bis 1970 legte er mehrere Zeitschienen gar übereinander („Photoptosis“, 1968).So gut wie nie zu hören ist indessen Yves Kleins „Symphonie Monoton Silence“ für 32 Orchester-musiker und 20 Sänger, in dieser Fassung notiert wohl von dem Komponisten Pierre Henry. Yves Kleinexperimentierte über Jahre hinweg mit der Idee, einen Klang wie den D-Dur-Akkord minutenlang ineinem Raum schweben zu lassen, gefolgt von anhaltendem Schweigen im Nachhall. 1960 umfasste

-

28

Monoton Silence" comprised an approximately 20-minute constanly varying D-major chord –and 20 minutes of silence. One thing common to all the compositions mentioned, however, isthe intended simultaneous experience in which space, perceived time, sound and silence enterinto a shifting of variously weighted forces. This is equivalent to the simultaneous shifting of forces in Maier’s paintings through invisibly communicating pipes.

It is worthy of note that in his most recent sketches and journals Herbert Maier has produced watercolours of a surprisingly representational nature. He, who is a careful, slow painter, andyet an animated speaker; who is sceptically disposed to the idea of progress, still repeatedlycircles in his mind around new, as yet unseen ways of painting; who despite bad experiencesstill seeks the experience of existential insecurity on long journeys; who for the sake of his artistic autonomy wants to know at all costs what other people have already cultivated – hewent on to draw portraits in 2008 and 2009 (Sketchbook / Crete 2008.5, see p. 128, 129).They mainly depict inhabitants of Crete, long-standing travelling acquaintances and the artist himself. They are accompanied by notes on biographies, history, incidents and time, butthe most astonishing things about them are their starkly shaded faces and their striking phy-siognomical contours – emphasised by their headwear. Anyone who can empathise with Herbert Maier’s attitude, who has gone through his school of perception, visual sensitizationand imagination and has understood the overall logic of his work will inevitably come to askwhether the silhouette is the form that, in addition to area and body, might also give Maier’snext cycle of works the chara cteristic of the individual. Knowing the deliberate way in whichhe approaches his motifs, and knowing his the interwoven relationships within his "Speicher",it would not be all that great a surprise – but still a risk in view of the enormous tradition towhich portrait and oil glaze painting belong. However, one may expect no less than the apparently impossible from art.

1) Gottfried Boehm, „Wie Bilder Sinn erzeugen. Die Macht des Zeigens“, Berlin 2007

-

29

die „Symphonie Monoton Silence“ einen rund 20-minütigen D-Dur-Akkord in wechselnder Gestalt– und 20 Minuten Stille. Allen genannten Kompositionen aber gemeinsam ist die avisierte Simultan-Erfahrung, bei der Raum, Zeitempfinden, Klang bzw. Lautlosigkeit ein unterschiedlich gewichtetesKräftegeschiebe eingehen. Dieses steht mit dem simultanen Kräftegeschiebe in Maiers Bildern gleich-sam durch verdeckt kommunizierende Röhren in Verbindung.

Das ist des Merkens würdig: In seinen jüngsten Skizzen und Gedankenbüchern aquarellierte Herbert Maier erstaunlich gegenständlich. Er, der sorgsam, abbremsend malt, doch lebhaft spricht;er, der dem Fortschrittsgedanken außerordentlich skeptisch gegenübersteht, doch mit seinen Ge-danken immer wieder um neue, ungesehene Bildweisen kreist; er, der trotz böser Erlebnisse immerwieder auf langen Reisen die Erfahrung existenzieller Haltlosigkeit sucht; er, der für seine künstleri-sche Autonomie „partout“ wissen will, was andere Menschen bereits kultiviert haben; er also zeich-nete 2008 und 2009 Porträts (Skizzenbuch /Kreta 2008.5, siehe Abbildungen S. 128, 129). Sie gebenvor allem kretische Einwohner wieder, langjährige Reisebekanntschaften, dazu den Zeichnendenselbst. Anmerkungen zu Biographien, Geschichte, Zwischenfällen und Zeit begleiten sie, doch dasErstaunlichste an ihnen ist ihr stark verschattetes Gesicht und ihre – durch die Kopftracht geförder-ten – prägnanten physiognomischen Konturen. Wer sich in die Sichthaltung Herbert Maiers ein-fühlen kann, wer durch seine Schule der Wahrnehmung, Sehsensibilisierung und Imaginationgegangen ist und die übergreifende Logik seiner Arbeit begriffen hat, der muss auf die Frage ver-fallen, ob die Silhouette wohl die Form sei, die Maiers nächstem Werkzyklus neben Fläche und Kör-per womöglich auch eine Charakteristik des Individuums geben könne. Es wäre im Wissen um seinebedachtsamen motivischen Annäherungen, auch in Kenntnis seines „Speicher“- Beziehungsge-flechts keine allzu große Überraschung – aber doch ein Wagnis angesichts der enormen Tradition,in der die Porträt- und die Lasurmalerei stehen. Doch Geringeres als das scheinbar Unmögliche darfman nicht erwarten von der Kunst.

1) Gottfried Boehm, „Wie Bilder Sinn erzeugen. Die Macht des Zeigens“, Berlin 2007

-

Malerei | Paintings 1990– 2004

-

001

Zeitfries | 1990 /1991 | Öl auf Leinwand | 190x1920 cm | Morat-Institut für Kunst und Kunstwissenschaft Freiburg

-

32

Speicher / für Morandi | 1993 | Öl auf Leinwand | 280x390 cm

-

33

-

34

Speicher /Magazin | 1995– 1999 | Öl auf Leinwand, Holz, Stahl | 160x379 cm

-

35

-

36

Ding / Speicher | 1999 | Öl auf Leinwand | 200x480 cm, dreiteilig

-

37

-

38

Speicher / Feld | 2000 | Diptychon, linke Tafel | 240x200 cm

-

39

Speicher / Feld | 2000 | Diptychon, rechte Tafel | 240x190 cm

-

40

Speicher | 2003 | Öl auf Leinwand | 240x280 cm

-

41

-

42

Speicher | 2000– 2003 | Öl auf Leinwand | 240x380 cm

-

43

-

44

Speicher | 2003 /2004 | Öl auf Leinwand | 240x660 cm, zweiteilig

-

001

-

Window-Paintings

-

001

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation /Clark Studio | 2004 | Bethany | USA

-

48

-

49

Speicher | 2004 /2005 | Öl auf Leinwand | 130x140 cm