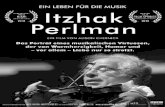

MARTHA ARGERICH ITZHAK PERLMAN

Transcript of MARTHA ARGERICH ITZHAK PERLMAN

MARTHA ARGERICH ITZHAK PERLMANSCHUManN · BACH · BRAHMS

Robert Schumann 1810–1856

Sonata for piano and violin No.1 in A minor, Op.105 1 I. Mit leidenschaftlichem Ausdruck 7.35 2 II. Allegretto 3.46 3 III. Lebhaft 4.48

Drei Fantasiestücke for piano and violin, Op.73 4 I. Zart und mit Ausdruck 3.12 5 II. Lebhaft, leicht 3.38 6 III. Rasch und mit Feuer 4.20

Johannes Brahms 1833–1897

7 Scherzo in C minor from the F–A–E Sonata, WoO 2 5.42

Johann Sebastian Bach 1685–1750

Sonata for keyboard and violin No.4 in C minor, BWV 1017 8 I. Siciliano: Largo 4.13 9 II. Allegro 4.51 10 III. Adagio 3.49 11 IV. Allegro 4.57

50.58

Itzhak Perlman violin Martha Argerich piano

2

Itzhak Perlman and Martha Argerich in conversation

Martha Argerich: Saratoga in 1998 was the only time we had played together, and that is a great pity, because I feel so stimulated performing with Itzhak. It’s truly a feast — it’s fantastic! Ours is a very special relationship; I’m completely enchanted.

Itzhak Perlman: My dream, always, was to play with Martha. The first time I heard her I thought, “Oh my God! I would love to play with her.” MA: You get inspired and stimulated by what you hear in the moment. Within that interplay a lot of things happen. It’s full of spontaneity. IP: It’s like having a conversation — MA: — and it was a nice, funny conversation! The Bach was wonderful. IP: You hear a colour, you look for it, and you start to interchange. It’s fantastic! MA: One plays music, and then it’s a question of spontaneity. Each time is different; that’s the goal. We play differently now than we did 18 years ago — differently even than yesterday! MA: There are two pieces that are totally new to me. I had never played the Bach sonata; I only discovered it for this recording. The Brahms, as well: never. The absolute first time was this recording! Bach is very important. I really like it; it’s really wonderful. IP: The first time I heard Martha play Bach I was absolutely amazed… the way you play Bach… like it was in your head, like you were born playing Bach — I am ecstatic! Working with Martha was a unique experience for me.

Although today we talk of sonatas for violin and keyboard as “violin sonatas”, all three composers featured here thought of their works in this form as sonatas for harpsichord or piano with violin accompaniment. They would have been the first to applaud such a duo of equals as we hear in this programme.

Johann Sebastian Bach was a brilliant organist and harpsichordist but also played the violin, although like many composers he preferred the viola. Until his time, instrumental sonatas were accompanied by “continuo”, usually a harpsichord and viola da gamba or cello, and the keyboard player worked from a “figured bass”, with sketchy indications of what to play. Bach wrote a few such works, but his six Sonatas, BWV 1014–1019, were among the first to be composed with a written-out keyboard part. They are trio sonatas: the keyboard player’s two hands account for two of the parts while the violin takes care of the other. Bach initiated them during his time in Cöthen and used them for domestic performances in the first instance — his autograph score, if it ever existed, is lost, but several excellent sources include a copy of the parts by his nephew Johann Heinrich Bach, his regular Leipzig copyist in 1724–27, with alterations and two movements of the sixth sonata in J.S. Bach’s own hand. It is entitled Sei suonate à Cembalo certato e Violino Solo, col basso per Viola da Gamba accompagnato se piace, so the musicians had permission to co-opt a viola da gamba player if they so wished (the present writer has never encountered such a performance). The sixth sonata in G went through several versions, with varying numbers of movements, but the others remained quite stable in the slow–fast–slow–fast form of the sonata da chiesa. The C minor has particularly lovely slow movements, the first a Largo in the siciliano rhythm often associated with Christmas, its melody pre-figuring the aria “Erbarme dich” in the St Matthew Passion, and the second a song-like Adagio. The fast movements are irresistibly rhythmic, in the fugal counterpoint that came instinctively to Bach. There is a long and honourable tradition of performing the Sonatas on piano and modern violin, as Martha Argerich and Itzhak Perlman do here.

Robert Schumann’s violin sonatas are late works, and although the first two are Romantic masterpieces, it is tempting to see their generally agitated state as evidence of the mental perturbation that eventually overwhelmed him. They were all but ignored by violinists until the celebrated team of Adolf Busch and Rudolf Serkin took them up — the duo’s 1937 recording of the first sonata, in A minor, marked a change in this fine work’s fortunes. Composed in five days during September 1851, when Schumann was having trouble with his Düsseldorf employers and, by his own account, was “very angry with certain people”, it has an unsettling, dark first theme — suited to the opening movement’s marking “With passionate expression” — which dominates the brief exposition; a second theme in C major is more open-hearted. After an agitated development, the recapitulation returns the first theme to dark, G-string-coloured A minor and the second to A major, and a stormy coda ensues. As he often does (think of the Piano Concerto), Schumann avoids a slow movement as such; instead he provides a wistful Allegretto, which is more like a cross between a gentle scherzo and an intermezzo. It is shaped like a rondo, with two episodes, and ends whimsically. Like the opening movement, the finale (Lebhaft, or lively) is in sonata form with a restless opening theme and a shorter contrasting theme. A new E major idea is introduced in the development; and after the recapitulation, a reminiscence of the sonata’s opening theme ushers in a substantial coda. Strangely, Schumann expressed himself dissatisfied with the sonata, but posterity gained because he almost immediately turned to composing the D minor Sonata, Op.121, a dramatic work in four movements. Premiered in March 1852 by Clara Schumann with the violinist Ferdinand David, the A minor Sonata was published the same year.

The three Fantasiestücke, Op.73, also in A, come from 1849, Schumann’s most productive year. Written for clarinet and all basically in ternary form, they were licensed for use by cellists but have also been commandeered by violinists and violists — there are slight differences between the clarinet and string versions. The song-like first piece, marked “Soft and with expression”, is in A minor and has a haunting quality. The second, “Lively, light”, begins

4

with a tumbling theme in A major; its central section in F is more lyrical and after the return of the lively music there is a quiet coda. The final piece, “Fast and with fire”, also in A major, mixes thematic material from the first two pieces into its distinctive character and ends with a splendid coda. Although this set of Fantasiestücke takes only about ten minutes to play and is not a “major” creation, it is among the most satisfying of Schumann’s chamber works.

The C minor Scherzo by Johannes Brahms had its origin in one of Schumann’s happiest inspirations. In October 1853 the young Brahms had just entered his life, and the violinist Joseph Joachim was also becoming one of his closest friends. One evening, when Joachim was expected within a few days, Schumann suggested to his protégés Albert Dietrich and Brahms that they should collaborate on a violin sonata based on the notes F–A–E, standing for Joachim’s motto “Frei aber einsam” (Free but lonely). Dietrich wrote an excellent opening Allegro, Schumann provided the Intermezzo and finale, and for the third movement Brahms composed a fiery scherzo — asserting his individuality, he eschewed the F–A–E motif but used material from Dietrich’s contribution. When Joachim played the sonata through with Clara, he guessed who had written what. Schumann soon composed his own opening movement and a Lebhaft (which he placed second) to make up his third violin sonata. Brahms’s scherzo was published in 1906, the F–A–E Sonata in 1935 and Schumann’s sonata in 1956.Tully Potter

Bien que l’on parle aujourd’hui de manière générale de sonates pour violon et piano ou violon et clavecin, les trois compositeurs représentés sur cet enregistrement considéraient leurs œuvres dans ce genre comme des sonates pour clavecin (ou piano) avec accompagnement de violon. Ils auraient certainement été les premiers à applaudir deux instruments placés sur un pied d’égalité comme on l’entend dans ce programme.

Brillant organiste et claveciniste, Jean-Sébastien Bach jouait aussi du violon mais il préférait l’alto, comme beaucoup de compositeurs. Jusqu’à son époque, les sonates instrumentales étaient accompagnées par un « continuo », habituellement un clavecin et une viole de gambe ou un violoncelle ; le claveciniste n’avait sous les yeux qu’une « basse chiffrée » qui lui indiquait quelles harmonies il devait jouer et il improvisait. Bach composa quelques partitions sur ce modèle. Par contre, ses six Sonates BWV 1014–1019 comptent parmi les premiers exemples du genre où la partie de clavier est intégralement écrite. Il s’agit de sonates en trio : les deux mains du claveciniste sont chacune chargées d’une partie, la troisième partie étant confiée au violon. C’est durant ses années à Cöthen que Bach a donné naissance à ces pages dont il a fait principalement un usage domestique. L’autographe est perdu mais il existe plusieurs sources excellentes, dont une copie réalisée par son neveu et copiste habituel à Leipzig, entre 1724 et 1727, Johann Heinrich Bach, qui comporte des altérations et où deux mouvements de la Sixième Sonate sont de la main de Jean-Sébastien lui-même. Elle est intitulée Sei suonate à Cembalo certato e Violino Solo, col basso per Viola da Gamba accompagnato se piace — on était donc libre d’ajouter une viole de gambe si on le souhaitait (l’auteur de ces lignes n’a jamais entendu ces sonates avec viole de gambe).

La Sixième Sonate en sol majeur passa par plusieurs versions successives, avec des variations dans le nombre de mouvements, mais les autres ne se départirent pas du modèle de la sonate d’église lent–vif–lent–vif. La Quatrième, en ut mineur, renferme des mouvements lents particulièrement beaux : un Largo au rythme de sicilienne, souvent associé à Noël, dont la mélodie préfigure l’air « Erbarme dich » de la Passion selon saint Matthieu, et un Adagio lyrique. Les mouvements rapides, écrits dans un contrepoint fugué qui venait à Bach instinctivement, ont un rythme irrésistible. Une tradition tout à fait honorable de jouer ces sonates au piano et au violon moderne existe depuis longtemps. C’est sous cette forme qu’on les entend ici, avec Martha Argerich et Itzhak Perlman.

5

Robert Schumann écrivit ses sonates pour violon et piano à la fin de sa vie. Si les deux premières sont des chefs-d’œuvre romantiques, il est tentant de voir dans leur caractère agité un signe des perturbations mentales qui allaient emporter le compositeur. Elles furent pratiquement ignorées des violonistes jusqu’à ce que le célèbre duo d’Adolf Busch et Rudolf Serkin s’y intéresse : l’enregistrement qu’ils firent en 1937 de la Première Sonate, en la mineur, changea le destin de cette page superbe. Schumann l’écrivit en cinq jours, en septembre 1851, alors qu’il avait des problèmes avec ses employeurs à Düsseldorf et qu’il était “très en colère contre certaines personnes”, selon ses propres termes. Le premier thème, sombre et troublant — dans la même optique que l’indication Avec une expression passionnée —, domine la brève exposition. Apparaît ensuite un deuxième thème en ut majeur plus franc. Après un développement agité, la réexposition ramène le premier thème dans le sombre la mineur, sur la corde de sol, et le deuxième en la majeur. Suit une coda orageuse. Schumann renonce à un mouvement lent en bonne et due forme, comme souvent (que l’on songe par exemple au Concerto pour piano), et à la place insère un Allegretto mélancolique qui fait un peu figure de croisement entre un scherzo délicat et un intermezzo. Sa forme est celle d’un rondo à deux couplets. Il s’achève de manière fantasque.

Comme le premier mouvement, le finale (Vivace), de forme sonate, présente un premier thème inquiet et un deuxième thème contrastant plus court. Une nouvelle idée en mi majeur est introduite dans le développement. Après la réexposition, une réminiscence du thème initial de la sonate débouche sur une coda substantielle. Curieusement, Schumann n’était pas satisfait de l’œuvre. La postérité y a gagné, puisqu’il s’est presque immédiatement lancé dans la composition de la Sonate en ré mineur op. 121, une page dramatique en quatre mouvements. La Sonate en la mineur fut donnée en première audition en mars 1852 par Clara Schumann et le violoniste Ferdinand David, et publiée la même année.

Les trois Fantasiestücke op. 73, en la mineur/majeur, de forme ternaire, datent de 1849, l’année la plus productive de Schumann. Elles sont destinées à la clarinette et au piano, mais la partie de clarinette peut être jouée ad libitum au violoncelle, et les violonistes et les altistes n’ont pas hésité à s’en emparer (il y a de petites différences entre la version pour clarinette et celle pour cordes). La première fantaisie est un chant en la mineur envoûtant qui porte l’indication Tendre et avec expression. La deuxième (Vivement, légèrement) commence par un thème en la majeur descendant, tandis que la partie centrale en fa majeur est plus lyrique. Après le retour de la première partie, la pièce se conclut sur une coda paisible. La troisième fantaisie (Rapide et avec fougue), également en la majeur, reprend du matériau thématique des deux premières en l’interprétant avec son caractère propre et se termine sur une coda splendide. Si ce triptyque op. 73 ne dure que dix minutes et n’est pas une œuvre « majeure », c’est l’une des meilleures partitions de musique de chambre de Schumann.

Le Scherzo en ut mineur de Johannes Brahms doit son existence à l’une des idées les plus heureuses de Schumann. En octobre 1853, le jeune Brahms venait d’entrer dans la vie de celui-ci, et il était aussi en train de devenir l’un des plus proches amis du violoniste Joseph Joachim. Un soir — on attendait l’arrivée de Joachim dans les jours suivants —, Schumann suggéra à ses protégés Albert Dietrich et Brahms qu’ils écrivent à trois une sonate pour violon et piano sur les notes F–A–E (fa–la–mi), acronyme de la devise de Joachim Frei aber einsam (« Libre mais seul »). Dietrich composa un superbe premier Allegro, Schumann se chargea de l’Intermezzo et du Finale, et en guise de troisième mouvement, Brahms sortit de sa plume un scherzo fougueux — affirmant son individualité, il évita le motif F–A–E mais reprit certaines choses de l’Allegro de Dietrich. Lorsque Joachim déchiffra la sonate avec Clara, il devina qui avait écrit quoi. Schumann composa ensuite son propre mouvement initial et un Lebhaft (« Vif ») qu’il plaça en deuxième position, donnant ainsi naissance à sa troisième sonate pour violon et piano. Le scherzo de Brahms fut publié en 1906, la Sonate F–A–E en 1935, et la sonate de Schumann en 1956.Tully PotterTraduction : Daniel Fesquet

6

Obwohl man heutzutage Sonaten für Geige und Tasteninstrument als „Violinsonaten“ bezeichnet, betrachteten alle drei der hier vertretenen Komponisten ihre Werke in dieser Gattung als Sonaten für Cembalo oder Klavier mit Violinbegleitung. Ein Duo auf Augenhöhe, wie es in diesem Programm zu hören ist, hätte sofort ihre Zustimmung gefunden.

Johann Sebastian Bach war ein brillanter Organist und Cembalist, spielte jedoch auch Violine, wobei er — wie viele andere Komponisten — die Bratsche bervorzugte. Vor seiner Zeit hatten in Instrumentalsonaten üblicherweise ein Cembalo, eine Viola da Gamba oder ein Cello die „Continuo“-Begleitung gespielt, während der Cembalist anhand eines „figurierten Basses“ mit skizzenhaften Spielanweisungen improvisierte. Bach komponierte ein paar Werke nach diesem Muster. Seine sechs Sonaten BWV 1014–1019 hingegen zählten zu den ersten, in denen die Cembalostimme auskomponiert war. Es handelt sich um drei Triosonaten: Die Hände des Cembalisten übernehmen zwei Stimmen, während die Geige die dritte spielt. Bach begann mit der Arbeit an diesen Sonaten während seiner Zeit in Köthen und hatte sie zunächst für den Hausgebrauch vorgesehen — falls es überhaupt jemals ein Autograph Johann Sebastian Bachs gegeben hat, ist es heute verloren, doch es existieren einige exzellente Quellen, unter anderem eine Stimmenabschrift seines Neffen Johann Heinrich Bach, seinem Hauptkopisten in Leipzig zwischen 1724 und 1727, die Änderungen und zwei Sätze der sechsten Sonate in J. S. Bachs eigener Handschrift enthält. Sie trägt den Titel Sei suonate à Cembalo certato e Violino Solo, col basso per Viola da Gamba accompagnato se piace. Die Musiker hatten demnach die Möglichkeit, eine Viola da Gamba hinzuzunehmen, falls sie dies wünschten (dem Autor dieses Textes ist eine solche Interpretation bisher nicht begegnet). Von der sechsten Sonate G-Dur gab es im Lauf der Zeit mehrere Fassungen mit einer unterschiedlichen Anzahl von Sätzen, während die anderen nicht vom Schema langsam–schnell–langsam–schnell der Kirchensonate abwichen. Die Sonate c-Moll weist besonders schöne langsame Sätze auf. Der erste davon ist ein Largo, das im häufig als weihnachtlich empfundenen Siciliano-Rhythmus steht und dessen Melodie auf die Arie „Erbarme dich“ aus der Matthäuspassion hindeutet. Der zweite ist ein liedhaftes Adagio. Die schnellen Sätze wurden in fugenhaftem Kontrapunkt gestaltet, den Bach instinktiv beherrschte, und sind unwiderstehlich rhythmisch. Die Interpretation am Klavier und auf einer modernen Geige geht auf eine lange und ehrbare Tradition zurück, der sich Martha Argerich und Itzhak Perlman hier ebenfalls anschließen.

Robert Schumanns Violinsonaten sind Spätwerke; und obgleich die ersten beiden als Meisterwerke der Romantik gelten, sind sie von einer aufgebrachten Stimmung geprägt, die man nur allzu gerne zum Beweis der geistigen Verwirrung heranziehen möchte, die Schumann am Ende übermannte. Bis das berühmte Gespann Adolf Busch und Rudolf Serkin sich dieser Sonaten annahm, war ihnen von Violinisten keinerlei Beachtung geschenkt worden — doch nach der Aufnahme der ersten Sonate a-Moll, die das Duo 1937 verwirklichte, änderten sich die Geschicke dieses wunderbaren Werks. Es entstand innerhalb von fünf Tagen im September 1851, in einer Zeit, als Schumann Schwierigkeiten mit seinen Düsseldorfer Arbeitgebern hatte und nach eigener Aussage über „bestimmte Leute“ sehr verärgert war. Die Sonate weist — passend zur Kopfsatz-Bezeichnung „mit leidenschaftlichem Ausdruck“ — ein verstörendes, düsteres Anfangsthema auf, das die kurze Exposition beherrscht; das zweite Thema in C-Dur gibt sich offenherziger. Nach einer aufgebrachten Durchführung führt die Reprise das erste Thema auf der G-Saite in ein düsteres a-Moll und das zweite Thema in die Tonart A-Dur, woraufhin sich eine stürmische Coda anschließt. Wie so häufig (man denke nur an das Klavierkonzert) vermeidet Schumann einen langsamen Satz im eigentlichen Sinn; stattdessen steht hier ein wehmütiges Allegretto, das vielmehr eine Kreuzung zwischen einem zarten Scherzo und einem Intermezzo darstellt; es ist mit zwei Episoden wie ein Rondo aufgebaut und endet launisch. Wie der Kopfsatz steht auch der Finalsatz („Lebhaft“) in der Sonatenform und weist ein rastloses Anfangsthema und ein kürzeres kontras tierendes Thema auf. In der Durchführung wird eine neue E-Dur-Idee vorgestellt; und nach der Durch führung leitet eine Reminiszenz an das An fangs thema der Sonate eine substanzielle Coda ein. Kurioserweise zeigte sich Schumann unzufrieden mit seiner Sonate, schenkte jedoch

7

Executive producer: Alain Lanceron

Special thanks to Charlotte Lee / Primo Artists & Frédéric Grün / Avanti Classic

Recorded live: 30 July 1998, Saratoga Performing Arts Center, New York State, USA (1–3)Recorded: 29–31 March 2016, Salle Colonne, Paris (4–11)Producer: Patti Laursen (1–3) · Daniel Zalay (4–11)Balance Engineer: John Dunkerley (1–3)Recording Engineer: Hughes Deschaux (4–11)Introductory notes and translations: C Parlophone Records Limited, a Warner Music Group Company.Photography: Jean-Baptiste MillotCover design: Paul Marc Mitchell for WLP Ltd. P & C 2016 Parlophone Records Limited, a Warner Music Group Company. www.warnerclassics.com C

All rights of the producer and of the owner of the work reproduced reserved. Unauthorised copying, hiring, lending, public performance and broadcasting of this record prohibited.

der Nachwelt fast unmittelbar danach noch die Sonate d-Moll op. 121, ein dramatisches Werk in vier Sätzen; die Sonate a-Moll wurde im März 1852 von Clara Schumann und dem Violinisten Ferdinand David uraufgeführt und im selben Jahr veröffentlicht.

Die drei Fantasiestücke op. 73, welche ebenfalls in der Tonart A stehen, stammen aus dem Jahr 1849, Schumanns produktivster Zeit. Sie wurden für Klarinette geschrieben und weisen alle praktisch eine dreiteilige Form auf. Gemäß der Partitur können die Stücke ad libitum von Cellisten gespielt werden, doch sie wurden auch von Geigern und Bratschisten beansprucht — zwischen der Version für Klarinette und der für Streicher gibt es geringfügige Unterschiede. Das liedhafte erste Stück mit der Bezeichnung „Zart und mit Ausdruck“ steht in a-Moll und ist von Eindringlichkeit geprägt. Das zweite, „Lebhaft, leicht“ beginnt mit einem fallenden Thema in A-Dur; sein Mittelteil in F ist lyrischer gestaltet, und nach der Wiederkehr der lebhaften Musik schließt sich eine ruhige Coda an. Im letzten Stück, „Rasch und mit Feuer“, ebenfalls in A-Dur, vereint sich thematisches Material aus den ersten beiden Stücken mit einem unverwechselbaren Charakter. Es endet mit einer überragenden Coda. Obwohl diese Sammlung von Fantasiestücken in gerade einmal zehn Minuten gespielt werden kann und keine „große“ Werksschöpfung darstellt, zählt sie zu Schumanns überzeugendsten Kammermusikwerken.

Das c-Moll-Scherzo von Johannes Brahms geht auf eine der besten Ideen Schumanns zurück. Im Oktober 1853 war der junge Brahms gerade in dessen Leben getreten, und der Geiger Joseph Joachim entwickelte sich zu einem von Schumanns besten Freunden. Eines Abends, wenige Tage vor einem Besuch Joachims, schlug Schumann seinen Schützlingen Albert Dietrich und Brahms vor, gemeinsam eine Violinsonate auf der Grundlage der Tonfolge F–A–E zu erarbeiten, das für Joachims Motto “Frei aber einsam” stand. Dietrich schrieb ein hervorragendes Anfangsallegro, Schumann steuerte das Intermezzo und das Finale bei und Brahms komponierte ein feuriges Scherzo für den dritten Satz — wobei er seine Eigenständigkeit durchsetzte, indem er das F–A–E-Motiv vermied und stattdessen Material aus Dietrichs Allegro verwendete. Als Joachim die Sonate mit Clara durchspielte, riet er, wer welche Teile des Werks komponiert hatte. Schumann schrieb bald seinen eigenen Kopfsatz und ein „Lebhaft“ (das er an die zweite Stelle setzte), um daraus seine dritte Violinsonate zu gestalten. Brahms’ Scherzo wurde 1906 veröffentlicht, die FAE-Sonate 1935 und Schumanns Sonate 1956.Tully PotterÜbersetzung: Stefanie Schlatt

8