Tolbert e Zucker 1983

-

Upload

luciana-godri -

Category

Documents

-

view

234 -

download

1

Transcript of Tolbert e Zucker 1983

7/27/2019 Tolbert e Zucker 1983

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/tolbert-e-zucker-1983 1/19

Cornell University ILR School

DigitalCommons@ILR

Articles & Chapters ILR Collection

3-1-1983

Institutional Sources of Change in the FormalStructure of Organizations: The Diffusion of Civil

Service Reform, 1880-1935Pamela S. TolbertCornell University , [email protected]

Lynne G. ZuckerUniversity of California, Los Angeles

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the ILR Collection at DigitalCommons@ILR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles &

Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@ILR. For more information, please contact [email protected].

Tolbert, Pamela S. and Zucker, Lynne G., "Institutional Sources of Change in the Formal Structure of Organizations: The Diffusion of Civil Service Reform, 1880-1935" (1983). Articles & Chapters. Paper 131.http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/articles/131

7/27/2019 Tolbert e Zucker 1983

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/tolbert-e-zucker-1983 2/19

utional Sources ofthe Formal

il Service Re form ,880-1935

ela S. Tolbert andG. Zucker

This paper investigates the d iffusion and institutionaliza-tion of change in formal organization structure, using dataon the ado ption of civil service reform by cities. It is shownthat when civil service procedures are required by the state,they d iffuse rapidly and directly from the state to each city.W hen the procedures are not so legitimated , they diffusegradually and the underlying sources of adoption changeovertime. In the latter case, early adoption of civil service by

cities is related to internal organ izational req uirem ents, w ithcity characteristics predicting adoption, while late adoptionis related to institutional definitions of legitim ate structuralform, so that city characteristics no longer predict theadoption decision. Overall, the findings provide strongsupport for the argum ent that the adoption of a policy orprogram by an organization is impo rtantly determ ined bythe extent to which the measure is institutionalized —whe ther by law or by gradual legitimation.*

1983 by Cornell University-8392/83/2801-0022/S00.75

y responsible for thergume ntand analysis. M. Craig

suggested th e topic of civi l servicereen J. McConag hy, Nancy

ma, Glenn R. Carroll, and P. Y.ded m ethodological advice;

advice throughou t theand to Marshall W. Meyer, John

Meyer, Will iam G. Roy, Herman Turk,

ky, and Jef frey P fef fer fo r their helpfulents on an earlier draft.

Explanations o f formal stru cture in organizations are as diver-

gent as the cu rrent approaches to organization theo ry. Tw oapproaches in particular have generated strong debate: oneviews organizations as rational actors, albeit in a complexenvironm ent (Thom pson, 1967; Blau and Schoenherr, 1971),wh ile the other view s organizations as captives of the ins titu-tional environment in wh ich th ey exist (Meyer and Rowan,1977; Zucker, 1982, 1983). Both approaches have importantimplications for the processes underlying diffus ion of an inno-vation in the form al structure o f organizations, the first pointingto the need for effectiveness or efficiency that may followadoption, the latter pointing to the need for legitimacy o f th eorganization in the wide r social structure. Thoug h thes e tw oapproaches are not necessarily incompatible, since organiza-tions may adopt innovations for differe nt reasons, they areseldom b oth investigated in the same empirical study.

Here, one important point of convergence is explored by usingboth perspectives to explain the adoption of civil serviceprocedures by municipal governm ents from 1880 to 1935.Adop tion of formal structure can be investigated in diverseorganizational con texts; here we exam ine the process in cities,often used as the c ontext for such research (e.g., Schnore andAlford, 1963; Knoke, 1982). Early adoption o f civil servicereform — before 1915 — appears to reflect e fforts to resolvespecific problems confronting municipal administrations, while

later adop tion is rooted instead in the growing legitimacy of civilservice procedures, wit h the d iffusion of societal norms servingto define local structure (Parsons, 1951). We first turn to a briefhistory of civil service reform, leading to a discussion of th einstitutionalization of r eform . We the n examine basic assump-tions in the organization literature about the sources of changein formal structure to establish the basis for the analysis ofadoption patterns of civil service procedures.

HISTORY OF MU NICIPAL CIVIL SERVICE

Civil service reform represents one of th e earliest attemp ts to"ration alize" local adm inistration by instituting a system of

written examinations for municipal appointees and by insulatingadministrative personnel from political influence th roug h ten-ure (White, 1949; Griffith, 1974). This entailed legally invest-

22/Admin is t r a t i ve Sc ience Quar t er l y , 28 ( 1983) : 22 - 39

Cop yr ight © 1983 . A l l ri ght s r eser ve d.

7/27/2019 Tolbert e Zucker 1983

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/tolbert-e-zucker-1983 3/19

7/27/2019 Tolbert e Zucker 1983

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/tolbert-e-zucker-1983 4/19

and implemented during this period: (1) its most rapid spreadoccurred after th e initial ferme nt subsided, indicating tha t it wa staken for granted, and (2) it is the mo st permanent andwidespread of all reforms acc omplished during this period.Both of these ch aracteristics are independent of the majordependent variable, adoption, w hic h w e used in our analysis.

Turning to the first point, the m ost acrimonious debates overcivil service procedures occurred before 1900; after 1910 theprocedures were generally discussed without much conflict,and by 1920 civil service procedures were accepted as theproperwaytoconductcitybusiness(Schiesl, 1977: 187).Table1 summarizes data coded from the major publication of theNational Municipal League, a federation of local organizationsactive in the promotion of civil service refo rm. A con tentanalysis of the proceedings of the League's annual me eting andof papers delivered at each meeting was carried out for fiveyears -1894,1900,1905,1909, and 1915. These records werecoded in tw o w ays. First, the total number of times a topicrelated to civil service reform wa s men tioned wa s coun ted ineach yearly report. Such mentions w ere divided into t w ocategories: criticisms of existing arrangements (e.g., refer-ences to spoils, machines, or political patronage), and proce-dures forimplem enting the reform (e.g., merit systems, promo-tion system s, and performance evaluation). Second, the totalamount of space devoted to discussing any of th e topics w asmeasured, yielding a summ ary number of pages for each year.In order to control for the length of each report, which variedconsiderably from year to year, each summ ary measure wasdivided by the total number of pages in the report for that year.

Table 1

Con tent A nalysis of Civil Service Discussion over Time, 1894-1915*

Stimulus forPublication reformtdate

18941900190519091915

Mean (S.D.)

5.77 (1.08)9.87 (2.99)2.60 (1.45)2.07 (0.67)

.20 (0.17)

Implementation*

Mean (S.D.)

1.43 (2.23)3.87 (1.70)2.77 (2.80)1.97 (2.00)

.60 (0.60)

Space devoted tocivil service refo rm

.041

.060

.020

.016

.018

•Se e Append ix for source s. All data taken as a proportion of the total numbe r of

pages.tC od ed as mentions of spoils system, patronage, machine politics.• Coded ast i on .

i mentions of merit system , promo tion system performa nce evalua-

Exhortations concerning the evils of the form er go vernmen talsyste ms , providing the s timulus for reform, showed a dramaticdecrease betw een 1900 and 1905. Discussion of the moretechnical aspects of implementation (merit systems, promo-tion, and performance evaluation) followed a similar pattern,tho ug h n either the rise from 1894 to 1900 nor the decline from1900 to 1905 was as sharp. The proportion of pages devoted to

general discussion of civil service re form sho we d a similar,thou gh less m arked, decline after 1900. These data indicate,then, that direct agitation for civil service adoption peaked in1900 and declined considerably there afte r. Since th e rapid rise

24/ASQ, March 1983

Copyright © 1983. All rights reserved.

7/27/2019 Tolbert e Zucker 1983

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/tolbert-e-zucker-1983 5/19

Diffusion of Civil Service

in adoption occurred afte r 1915, it appears to have occurred inthe con text of the recognized need for new procedures, ratherthan as a result of e xtens ive direc t pressure (or of regionaldiffusion, wh ich had only a weak effe ct).1 In general, then, th ereduction in the amo unt of debate and discussion of thestimulus and implem entation of th e reforms in the League'sproceedings indicates that the reform s had increasing legiti-macy and we re more taken for granted.

Turning now to th e question of perm anence, regardless ofwh ethe r the procedures were transmitted through state regu-lation or gradual adoption by m unicipal governm ents, civilservice re form caused changes in city gove rnmen t organizationthat became enduring elements of structure. Cities seldomdiscarded civil service once it was a dopted, and federal andstate legislation after 1935 increasingly required the use of localcivil service procedures. The rapid institutionalization of thereform rested on the assumed isomorphism between it and theideal rational bureaucratic form (Zucker, 1983). Governmentorganizations, increasingly oriented to service delivery, weremodeled after the business corporation, where personnel

selection and prom otion w ere presumably based on merit, notfamilial or othe r personal ties. Other municipal reforms pro-mo ted during this period, such as the city manager form ofgovern me nt, nonpartisan ballots, and city-wide elections, alsoreflected the drive to "ratio nalize " m unicipal adm inistration.

A hundred years after the ir initial introduc tion, civil servicestructure and procedures are nearly universal. Hence, one ofthe key defining elements of institutions — "es tablishm ent ofrelative permanence of a distinctly social so rt" (Hughes, 1936:180) — is presen t in the case of t he civil service. Localgovernment structure became clearly patterned by the wider

culture over tim e; civil service procedures became u biquitous.

Of c ourse, not all variables related to adop-t ion can be explored here. We focus onthose identified by historians of this periodas most significant. Unlike most otherstudies of reform processes (e.g., Knoke,1982), regional differences we re nonsig-nificant except in the case of the Southwhich, as expected from prior research,lagged behind t he oth er regions. Tables

sho wing this data are available fromPamela S. Tolbert. Althou gh th e southe rnstates wer e tardy in adopting civil servicereform, excluding them from the analysisbelow had virtually no impact on th e re-sults; they were the refore included.

CHANGE IN THE FORMAL STRUCTURE OFORGANIZATIONS

Institutionalization refers to the process through which com-ponents of formal structure become widely accepted, as bothappropriate and necessary, and serve to legitim ate organiza-tions. Mo st funda men tally, the process is one of social change.This process may occur in diffe ren t w ays (H emes, 1976): (1)initial endogenous chang e may take place w he n the process is

gradual and not required and/or (2) exogenous change may takeplace later in the process or wh en the process is required. Thatthe differe nt processes of change are not incompatible can beseen in their m utual influences over the course of civil servicereform. Before examining this in more detail, som e generalperspectives on sources of organizational structure need to beconsidered.

For the most part, organizational theoris ts have analyzed formalstructure as if it were static, focusing on its sources at one pointin time. Radically differen t v iew s of these sources haveemerged. In one view, forma l structure arises from internalsources, either directly (Scott, 1975) throu gh p roblems ofcoordination and control (e.g., Anderson and Warkov, 1961;Woodward, 1965; Blau, 1970) or indirectly (Aldrich and P fef fer ,1976) thr oug h power, leadership, and socialization to specificorganizational roles, ofte n m ediating environmental effe cts

2 5 / A SQ , M a r c h 1 9 8 3

Cop yr ight © 1983. A l l rights reser ved.

7/27/2019 Tolbert e Zucker 1983

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/tolbert-e-zucker-1983 6/19

(e.g., Chi ld , 1972; Thorn ton and Nard i , 1975; Pfe f fe rand

Sa lanc ik , 1978) . From the o the r v iew po in t , fo rm a l s t ruc tu re

ar ises f rom ex te rna l sources , f rom the d i rec t e f fec ts o f the

inst i tu t ional environment. In order to surv ive, organizat ions

co nfo rm to w ha t is soc ie ta l ly de f ine d as appropr ia te and

eff ic ient, largely d isregarding the actual impact on organiza-

t iona l per fo rmance (Meyer and Rowan, 1977: 353 ; Zucker ,

1982).

Thes e perspe c t ives a re no t incompat ib le , bu t ra ther po in t tocond i t ions under w h i ch cha nges in the fo rma l s t ruc tu re o f

organizat ions wi l l der ive from internal or inst i tu t ional sources.

Before changes in fo rma l s t ruc tu re become soc ie ta l ly leg i t i -

ma ted and/or requ i red , they a re ad op te d — m uch as is any o the r

innovat ion — th ro ug h a p rocess o f d i f fus ion depend ing in large

part on the value of the changes for the in ternal funct ioning of

th e organizat ion (Utterback , 1 97 1; Ald r ich , 1979). It is not

a lways easy to assess th is , o f course , espec ia lly w he n the

outputs of the organizat ion are d i f f icu l t to evaluate. Under these

cond i t ions , the need fo r changes wi l l o f ten be de termined by

the lack o f consensus , o r degree o f con f l ic t , w i th in the o rgan i -

za t ion (Cyer t and Ma rch , 196 3; M arch and Olsen , 1976; Pfe f -fer , 1981). Fundamental ly , ex is t ing structure comes to be

v iewed as p rob lemat ic , and the " log ic o f good f a i t h " ( M e y e r

and Row an, 1977) is d is rup ted . Th ere f o re , to the ex ten t tha t an

organizat ion is an early adop ter of an innovat ion in form al

s t ruc tu re , i ts dec is ion to adopt w i l l dep end on the degree to

wh ich the change improves in te rna l p rocess ( fo r example , by

s t reaml in ing p rocedures o r reduc ing con f l ic t ) .

In contrast, once h is tor ica l cont inui ty has establ ished their

impor tan ce (Berge rand Luck ma nn, 1967; Zucker , 1977) ,

chang es in fo rm a l s t ruc tu re a re adop ted because o f the i r

societa l leg i t imacy, regardless of their va lue for the in ternalfunc t ion ing o f the o rgan iza t ion . When some organ iza t iona l

e lem ents b eco me ins t i tu t iona l ized , tha t is , w he n the y a re

wide ly unders tood to be appropr ia te and necessary compo-

nents of ef f ic ient, rat ional organizat ions, organizat ions are

under cons iderab le p ressure to incorpora te the se e lem ents in to

their formal s tructure in order to mainta in their leg i t imacy. By

doing so, "an organizat ion demonstrates that i t is act ing on

co l lec t ive ly va lued purposes in a p roper and adequate ma nne r"

(Meyer and Rowan, 1977: 319). This may be necessary to

ens ure access to var ious resourc es that the organizat ion need s

for surv iva l ( in the case of c i t ies, favorable bond rat ings,

m em ber sh ip in so m e na t iona l o rgan iza tions , s ta te o r federa lfun ding , etc.) . It is as su m ed tha t th e adopt ion of an inno vat ive

mea sure m ay have l i tt le o r no e f fec t on th e ac tua l e f f ic ien cy o f

organizat ional operat ions; i ts adopt ion fu l f i l ls symbol ic rather

than task- re la ted requ i rements . Hence, to the ex ten t tha t an

organizat ion is a la te ado pter of an innovat ion in form al s truc-

tu re , i ts dec is ion to adopt w i l l depen d on th e degree to w h i ch

the re is a co m m on unders tand ing tha t the chan ge is necessary

for ef f ic ient organizat ional performance (Walker, 1969).

Tw o basic p rob lems a re con f ro n ted h e re : Wha t is the e f fec t o f

exp l ic it h ie ra rch ica l leg i t imat ion o f a re f o rm , and w ha t is the

e f f ec t o f rap id and wide spre ad leg i t ima t ion o f a re fo rm on i tssubs eque nt adopt ion? The f i rs t ana lys is com pares the e f fec t o f

h ie ra rch ica l con t ro l by the s ta te wi th the e f fec t o f nonman-

dated spread o f re fo rm on th e ra te o f adopt ion . In the secon d

26/ASQ, March 1983

Copyright © 1983. All rights reserved.

7/27/2019 Tolbert e Zucker 1983

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/tolbert-e-zucker-1983 7/19

Diffusion of Civil Service

Work to date on the adoption process hasbeen largely descriptive, providing fe w pre-dictions that generalize beyo nd a particularcase. In this paper we d o not attemp t toconstruct an explanation for all types ofadoption processes but to specify a particu-lar class o f adoption situations to which our

generalizations are expec ted to apply.There are a number o f impo rtant relationsthat w e do not consider here. First, differ-

ent mod es of gradual adoption are notconsidered. The innovation may produce astriking increase in effective ness or effi-ciency and be rapidly adopted on "ra tion al"grounds, or as in the case of a technologicalinnovation, the value may be assessed assuperior and the innovation m ay be rapidlyadopted simply on the basis of professionalopinion. Second, we do not explore sourcesof resistance. Some adoptions, even whensupported by professional opinion, meetwith much more resistance than others(e.g., computerized accounting systems insmall businesses or fluoridation of city

water supplies). Finally, we explore only alimited set of factors tha t may lead toadoption, though w e have focused onthose id entified by historians as mostsignificant.

analysis, changes in the a bility to predict adoption on the basisof particular organizational characteristics from the earlyperiods to the later periods are explored in detail. It is expec tedthat when innovations are rapidly institutionalized, early adop-tion can rest on either the force of th e hierarchical s tructurethat requires the reform or on particular characteristics thatmake it appropriate to adopt the reform; however, whileparticular characteristics may predict early adoption, they losetheir explanatory power rapidly.

2 In contrast, if the adoption failsto become legitimated, the same characteristics that predictearly adoption continue to predict w hic h units are more likely toadopt through out t he tim e period (Hamblin, Jacobsen, andMiller, 1973: C h. 7). In such cases, regional effe cts andparticular sets of characteristics, such as high status, thatidentify a set of "in no va tor s" e me rge as central predictors ofadoption (Rogers, 1962).

LAW AND HIERARCHICAL LEGITIMATION

In organizational netw orks in w hic h th e control of resources andauthority is centralized in a few pow erful organizations, the

institutionalization of an element of formal structure is largelydependent on its legitima tion by those organizations (Benson,1975). Once legitimated by higher level organizations, throughlegal mandate or other formal means, dependent organizationsgenerally respond by rapidly incorporating th e elem ent into theirformal struc ture. This adoption is seldom problematic wh en theelemen ts have high face validity and there is commo n agree-me nt concerning their overall utility. Ho wever, under certainconditions, strong resistance can develop. For example, lack ofconsensus on the value of an innovation, such as curriculumrefo rm in public schools (Rowan , 1982), can lead to failure toadopt or to early rejection of the innovation. In addition, strongcoalitions or interest groups can block a hierarchically mandatedchange, as happened w ith busing to integrate schools.

W e do not explore the con ditions underlying such resistance; itis important simply to note that legal requirements do notalways ensure adoption. In the case of civil service, states, suchas Wisconsin, wi th s trong interest groups that opposed adop-tion failed to pass statew ide m easures. How ever, in stateswh ere there w as little organized opposition, and consensusconcerning the potential value of th e innovation was high, thespeed and pattern of d iffusion among cities under state man-date are expected to reflect the degree of hierarchical legitima-t ion; diffusion w ill occur from the state to each city, rath ertha namong cities. Wh en states pass laws requiring municipal civilservice, it is expected tha t there will be a landslide effe ct in thefirst year of imp lementation of the law, wit h the state influenc-ing the remaining cities to adopt in subsequent years. Theseeffe cts should be apparent in the thre e states adopting suchlaws during the tim e period investigated here.

Sample

Adop tion was d efined as the passage of any legal requirementfor the institution of civil service procedures. In mos t cases, civilservice requirements affected only parts of city government;fire and police departments w ere frequently th e first affected.Data on adoption of civil service procedures, 1880 to 1935, wer ecollected for 167 cities. Of the se 167 cities, 74 are located in thethre e states that adopted civil service reform requirements for all

2 7 / A SQ , M a r c h 1 9 8 3

Cop yr ight © 1983. A l l rights reser ved.

7/27/2019 Tolbert e Zucker 1983

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/tolbert-e-zucker-1983 8/19

cities prior to 1930 and 93 are in states that had no suchrequirement.

State wide laws requ iring municipal civil service were passed byNew York in 1883 and by Ma ssachuse tts in 1884. Ohio m adecivil service mandatory for fire and police departm ents under itsmunicipal code in 190 2; this code was extended in 1908, and in1912 municipal civil service was given constitutional status(Griffith, 1974). In the analysis of the three states mandating

civil service, the 74 cities having a population of 50,000 orgreater in 1930 we re included. Data were aggregated fo r thethre e states requiring adoption both because of the smallsample size and because initial analyses indicated no significa ntdifferences in the patterns of adoption between states.

The 93 cities located in states that did not mandate civil servicewere drawn from a sample of 150 cities randomly selected froma sampling frame of all cities having a population over 25,000 in1930, stratified by size. The cities were selected from the 150by using tw o criteria: (1) cities of less than 50,000 we reexcluded, because data on smaller cities proved extremely

scanty, particularly in the earlierdecade s, and (2) cities in statesmandating civil service w ere excluded.

The data sources for all the analyses reported in this paper arelisted in the Appendix. Charles N. Halaby and M. Craig Browninitially conceived of a longitudinal quantitative study of theadoption of civil service system s by American city govern-me nts. The Civil Service R eform League reports that makesuch a study po ssible we re b rough t to our attention in 1977 bythem.

Findings

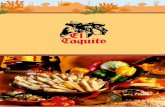

In th e Figure, w hi ch plots th e actual time of adop tion of civilservice procedures, 1880 to 1930, w e can compare the differ-ences in the rate of adoption of civil service reform s betw eencities in states tha t required it and those th at had no require-me nts. Wh en adoption was required by the state, th e rate ofadoption was rapid. W ithin t he first ten years, over 60 percentof all cities adop ted civil service procedures; the n the rateslowed, but all cities have adopted w ith in 37 years. In sharpcontrast, cities wi th no such requirement initially adopted m uchmore gradually. In the first fift een years the rate of adoptionwas low. After this period, however, the rate of adoptionprogressively accelerated over time. At the en d of the time

period considered here, a little over 60 percent of th ese citieshad adopted civil service procedures, their rate of adoptionabout equal to tha t reached after te n years by cities required toadopt.

There is also some evidence that th e underlying process ofadoption is different for these two groups of cities. Twomode ls, incorporating differe nt assu mptions about the sourcesof diffu sion , we re estima ted for both groups of cities (Coleman,1964: 49 5-5 05 ). Bo th models were operationalized using al-gorithms developed inZucker(1975). Cities that adopted civilservice procedures w he n no statewide req uirement e xisted can

be treated as sets of small separate groups, wit h full comm uni-cation betwee n some but no communication betwee n others.Using a diffus ion mode l of decentralized influence , the overallfit was acceptable, though the estimated values diverged from

28/ASQ, March 1983

Copyright © 1983. All rights reserved.

7/27/2019 Tolbert e Zucker 1983

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/tolbert-e-zucker-1983 9/19

Diffusion of Civil Service

100 T

90 •

80-3uiO

>I

70'>oozI -a.OQ<UJ

toU.

O

UJO

fSzUJODC

UJ

a.

60-i

50

40

30 -i

20

10-i

, "

T "

10

T

20 30 40 50

YEARS FROM INITIAL ADOPTION

—A doption by cities in states manda ting ad option (/?2 = .99, Error = .038)—A doption by cities in states not mandating adoption {R

2 = .89, Error = .408)

Figure. Rate of adop tion of civil service by cities over 50-year tim e period.

Full results, including estimation of thedifferent models of adoption proposed byColeman (19641, can be obtained fromPamela S. Tolbert

the actual values in both the initial adoption period (overesti-mated) and the adoption after 1912 (underestimated). In con-trast, in those cities that adopted civil service procedures w he n

the state required it, diffusion from the source was almostimm ediate, so that adoption by cities in the first year does not fita diffus ion mo del, even one that assum es centralized influence.In our case, over a third of t he sam ple adopted procedures inthat first year, creating a landslide rather than a diffusion effect.However, the remaining years showed a pattern of singlesource diffusion that yielded a close fit betw een th e actual andestima ted values. Hence, as these results demon strate, tw ofundamentally differ ent patterns of adoption, resting on differ-ent processes, occurred as cities adopted civil serviceprocedures.

3

GRAD UAL ADOPTION PROCESSW e argue that, w he n not mand ated by state governmen t, civilservice was adopted at first in response to conflict generated bydiffere nt conceptions of the appropriate role and function of

29/ASQ, March 1983

Copyright © 1983. All rights reserved.

7/27/2019 Tolbert e Zucker 1983

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/tolbert-e-zucker-1983 10/19

munic ipal government held by o lder, establ ished groups and/or

com m un ity busine ss leaders, and tho se held by low er statu s

groups in the community , part icu lar ly the pol i t ica l ly organizedimmigrants. In l ine with work by h is tor ians on c iv i l serv ice

adopt ion and by students of munic ipal s tructure, we expect

early ado pte rs of civi l service ref or m to have a relatively larger

fo re ign-born popu la t ion , more midd le c lass mem bers (smalle rpropo rt ion of m anu factu r ing w ag e earners and i ll i terates), and a

narrow scope of administrat ion ( lower munic ipal expenditures).

I t is a lso expecte d that th ey w i l l tend to be larger and yo unge r

than nonadopters, a l though the overal l e f fects of age and s izeare so m ew ha t unclear s ince they are apt to be inversely re lated

to adopt ion . The se var iables are d iscussed in more deta i l be lo w.

Our predic t ion, in contras t to th e ear l ier research , is tha t w hi le

these var iables are important determinants of the adopt ion of

an innovat ion ear ly in the process of i ts d i f fus ion, they become

re lat ively poorer p red ic to rs as the re fo rm measure beco me smore ins t i tu t iona l ized . O ve r t i m e, adopt ion is expec te d to

become independent of in ternal factors, as external def in i t ions

o f modern mun ic ipa l admin is t ra t ion become more s ign i f ican t .

In l ine wi th ear lier emp ir ica l wor k on inst i tu t ional izat ion (Zucker,1977), i t is exp ecte d that as a ref orm me asur e is increasingly

taken for grante d because of socia l leg i t im at ion, c i t ies wi l l begin

to adopt it as a "social fact," regardless of any particular city

character is t ics. Hence, the abi l i ty of these c i ty var iables, takenas a wh o le , to d i f fe ren t ia te be tw een adopters and nonadopters

sho uld progress ively decl ine. I t is a lso possib le that the ef f ec -

t ivene ss of a part icu lar var iable may chan ge, such tha t i tbecomes a re lat ive ly better or poorer predictor at d i f ferent

points in t im e; our pr imary concern here, how eve r, l ies not in

trac ing the effects of specif ic c i ty character is t ics on adopt ion,

bu t in assess ing th e e f fe c ts o f overa l l d i f fe ren ces be t we en

adopters and nonadopters over t ime.

W e do not ass um e that a part icu lar set of character is t ics is

a lways or usual ly re lated to adopt ion of innovat ion, but rathertha t thos e charac te r is t ics tha t make i t more " ra t ion a l " to adopt

wi l l be impor tant ear ly in the d i f fus ion process. This may expla in

why no consistent set of character is t ics predisposing indiv idu-

a ls or organizat ions to adop t innovat ions have been d iscov ered ,despite considerable research a imed specif ica l ly at character is-

t ics as explanatory var iables (Dow ns and M oh r, 1976). Each

spec if ic innova t ion shou ld be re lated to a set of ad opter

charac te r is t ics , on ly som e o f w h i ch w i l l over lap w i th o ther

innovat ion s unless they are l inked to a co m m on ju st i f ica t ion.

City Character is tics and Refo rm: Mea sures

Before turn ing to the analys is , the character is t ics that have

previously been ident i f ied as predictors of adopt ion of c iv i l

serv ice reform need to be more fu l ly d iscussed. Whi le c iv i l

se rv ice re fo rm wa s promo ted by the Progress ive Mo vem en t asincreas ing the e f f ic ien cy and e f fec t iv enes s o f the ad min is t ra -

t ion o f local gov ernm ent (W oodru f f , 1903; The len , 1972), som e

histor ians ha ve argued tha t c iv il serv ice re form wa s used as a

pol i t ica l weapon by socia l groups ( the industr ia l is ts or the

midd le c lass) to gain or mainta in their pol i t ica l domina nce (e.g.,a l lowing the m to de f in e admin is t ra t ive pos i t ions in such a way

as to vi r tua l ly ensure the app o in tm ent o f the g roup 's me mb ers

to mun ic ipa l o f f ice ) .

30/ASQ, March 1983

Copyright © 1983. All rights reserved.

7/27/2019 Tolbert e Zucker 1983

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/tolbert-e-zucker-1983 11/19

Dif fus ion of C iv i l Serv ice

To reduce problems of multicollinearity,both the number of manufacturing wageearners and municipal expenditures (dis-cussed under "Sco pe") were linearly re-gressed on th e log of city size (Maddala,1977).

SLiebert's (1976: 33) research indicates tha tthis m easure is strongly correlated with thenumber of functions performed by munici-pal governm ents (r = .72).

I m m i g r a n t s a n d r e f o r m . Loca l re fo rm e f fo r ts have o f te n been

v iew ed as a response to th e g ro wt h o f m ach ine po l it i cs

assoc ia ted w i t h the t remendo us in f lux o f immig ran ts in to

Amer ican c i t ies dur ing the la te n ine teenth and ear ly twent ie th

centur ies (Hofs tad te r , 1956; Wol f ingerand F ie ld , 1966) . S ince

civ i l serv ice reform el iminated pol i t ica l patronage, i t repre-

sente d a par t icu la r ly e f fe c t iv e wa y fo r the t rad i t iona l Ang lo -

Am er ican e l it es to a t tack immig ran t -dom ina ted mach ines by :

(1) esta bl ish ing cr iter ia for ap po intm en t to of f ice , inc luding

s tandards o f educat ion o r l i te racy tha t were d i f f icu l t fo r immi-

grants to meet, and (2) establ ish ing ru les governing tenure, to

pro tec t appo in tees f rom pat ronage- induced tu rnover in c i ty

gov ern me nt (Hays , 1964; Gordon, 1968). Accord ing to th is

a r g u m e n t , r e f o r m w o u l d b e m o s t c o m m o n a m o n g c i ti e s w i t h

la rge fo re ign-born popu la t ions , where tens ions be tween o lder

Ang lo -Amer ican groups and newly a r r ived immigran ts wou ld be

h ighes t . Th is is me asured here as th e percentage o f the

popu la t ion tha t is fo re ign-born .

Soc ioeco nom ic bases of re form. Recept iv i ty to mun ic ipa l

re fo rm has a lso been linked to the soc ioe cono mic com pos i t ion

o f a c i ty , w i t h the suppor te rs o f re fo r m com ing f ro m t heeducated and pro fess iona l ized midd le c lass . Two d i f fe ren t

in te rpre ta t ions bo th sugges t tha t mun ic ipa l re fo rm rece ived i ts

mo st en th us ias t ic suppor t in c i t ies w i th a large propor t ion o f

educa ted , wh i te -co l la r c i t izens . On the on e hand, the bas ic

va lues o f the new ly em erg ing m idd le class — e f f ic iency ,

impar t ia l i ty , ra t iona l i ty — were most cons is ten t w i th those

under ly ing re fo rm (W iebe, 1967) ; on the o ther ha nd, how ever ,

midd le c lass re fo rmers were mot iva ted by p ragmat ic concerns

o f secur ing repre senta t ion o f the i r po li t ica l and eco nom ic

in te res ts in local gov ernm ent (Hays , 1964; W ein s te in , 1968).

The soc ioeconomic c omp os i t ion o f a c i ty wa s measu red in tw o

wa ys : the percentage o f i l li te ra tes wa s used as a mea sure o f

the leve l o f educat ion in a c i ty , and the num ber o f man ufac tu r -

ing wa ge ea rners (res idual ized on c i ty s ize)4 wa s use d as a roug h

index o f the concent ra t ion o f members in b lue-co l la r occupa-

t ions . Bo th were expec ted to be inverse ly re la ted to the

adopt ion o f c iv i l se rv ice re fo rm.

S c o p e . A th i rd fac to r tha t has been sugge sted to have a f fe c te d

the adopt ion o f re fo rm is scope, o r the number o f func t ions

pe r fo r m ed by loca l gov ernm ent (L ieber t, 1976 ; Turk , 1977) .

Accord ing to th is a rgument , c i t ies wi th b roader scopes encour-

aged the deve lopment o f compet ing spec ia l in te res ts and

higher levels of pol i t ica l act iv i ty by of fer ing greater opportunityfo r po li t ica l in f luenc e. These c i t ies tended to have h igher

res is tance to re fo rm, because re fo rm measures f requent ly

l imited accessib i l i ty to formal leadership posit ions. In contrast,

c i t ies in w h i ch " na r ro w scope presumab ly l im i ted the re levance

of th e gov ern me nt and o f i ts leaders h ip v is -a -v is many type s o f

poss ib le in te res ts " had h igher ra tes o f re fo rm (L ieber t , 1976:

97). Tota l munic ip al expen ditur es (res idual ized on c i ty s ize) we re

used as an ind ica to r o f governmenta l scope;5

th is var iable was

expected to be inversely re lated to the adopt ion of c iv i l serv ice

r e f o r m .

A g e . Another poss ib le de te rminant o f the adopt ion o f re fo rm isc i ty age . Acc ord ing to S t inc hco mb e (1965) and severa l recent

empir ica l s tud ies (K imber ly , 1975; L ieber t , 1976; Meyer and

B r o w n , 1977), the formal s tructure of an organizat ion tends to

31 / A S Q , M a r c h 1983

Copy r ight © 1983. A l l r ights rese rved.

7/27/2019 Tolbert e Zucker 1983

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/tolbert-e-zucker-1983 12/19

ref lec t the h is tor ica l era in w hi ch i t or ig inated, s ince organiza-

t ions general ly adopt and reta in the fo rm that wa s predo min ant

at that t ime. By th is reasoning, i t would be expected thatyounger c i t ies , thos e tha t were jus t beg inn ing to deve lop w he n

the mun ic ipa l re fo rm movement swept the count ry , wou ld bemore l ike ly to adopt reforms than o lder c i t ies whose munic ipal

s t ruc tu res we re a l ready we l l en t renched and o f ten suppor tedby ves ted in tere sts (see W il l iams on and Swan son , 1966, on age

of c i ty and adopt ion of industr ia l innovat ions). Age wa s m ea-sured as the year in which a c i ty became incorporated; agether e fo r e remains the sam e fo r each c i ty th roug hou t a ll the

t ime per iods. Given th is measurement, age is expected to beposit ive ly re lated to adopt ion of c iv i l serv ice re for m .

Size. A final factor that has also been l inked to the adoption of

munic ipal refo rm is c i ty s ize. Al tho ug h studies of d i f fe ren ttypes of reform measures have found s ize to have a vary ing

impact on adopt ion (e.g., Kessel, 1962; Schnore and Alford,1963), s tudie s that have specifica l ly exa min ed c iv il serv ice

re fo rm have found a s imp le pos i t ive re la t ionsh ip be tw een the

adopt ion of the reform and c i ty s ize (c f . , Wolf inger and Fie ld,

1966). City size was logged to normalize its distr ibution.

Data and Analysis

The effect of these var iables on c i t ies ' adopt ion of c iv i l serv iceme asure s wa s analyzed using a proport ional hazards regres sion

mo del (Cox, 1972). First developed in th e b io logical sc iences ,models of th is type have been adopted by socia l sc ient is ts to

explore a var iety of phe nom ena (cf. , Hannan , Tum a, and

Gro enev eld, 1 978; D iPrete, 1 981 ; Carrol l and Delacro ix , 1982).A centra l advantage of the se mo dels over othe r cros s-sect iona l

appro aches , such as logi t or probit , is th e expl ic i t incorporat ionof the t iming of changes in a qual i ta t ive dependent var iable

(Carroll, 1982). Essent ia l ly , the o bject ive is to m odel th e instan -taneo us transit ion rate, or th e transit ion probabi li ty of mov ing

from one d iscrete state to another over an in f in i tes imal ly smal l

uni t o f t ime. Thus, the transit ion rate between state/ and statek, w he re p is th e probabi l i ty of such a transi t ion , is de f ine d as

At-»0 At

This hazard rate may de pend both on t im e and on a set ofexogenous var iables.

Here we use part ia l l ike l ihood est imat ion procedures, based onwo rk by Cox (1972). This approach requires less in for ma tion fores t ima t ion and makes we aker parametr ic assum pt ion than fu lll ike l ihood me tho ds . W it h part ia l l ike l ihood , th e l ike l ihood fu nc-t ion has tw o com po nen ts, one that rests on the order of even tsand another that rests on the exact t iming of the events.Ma ximiza t ion of the l ike l ihoo d funct io n is based only on th e f i rs tcomponent; thus, correct order ing of the events is required.Est imators obta ined with th is procedure, l ike fu l l l ike l i hoodest imators, have excel lent asymptot ic propert ies (Tuma, 1980).

The general form of the model is

h llt(t\X) = h0{t)exp(pX)

or

•\n{hik(t\X)lh0(t)}=pX,

32/ASQ, March 1983

Copyright © 1983. All rights reserved.

7/27/2019 Tolbert e Zucker 1983

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/tolbert-e-zucker-1983 13/19

Diffusion of C ivil Service

where h(t) is the hazard fun ction , or the rate of leaving aparticular state among a set of units, in this case, moving fromnonadoption o f refo rm (0) to adoption (1). X isa vector ofcovariates, (3 is a vector of regression coe fficients andh0(t) is ahazard function fo r a unit wi th X = 0 (Hopkins, 1981).

Data. The data sources for adoption have already been dis-cussed and are fully presented in the A ppendix. Also listed inthe A ppendix are the sources of data on city characteristics,

gathered from the decennial censuses, from 1890 to 1930.Missing data were estimate d using regression to generatepredicted values (Maddala, 1977). Only in one case, the per-centage of illiterates in the population in the first tim e period,was estimation unreliable; the variable was excluded from theanalysis in that period.

Unfortunately, the de finitions of some of th e independentvariables changed over tim e and were noncomparable. Thisproblem is frequen tly enco untered in the use of early censusdata. As a consequen ce, pooling of th e data is not possible.W hen thes e data are treated as comparable, serious estim ation

errors und oubtedly occur, since some central measures, suchas the basic definition o f m anufacturing indu stries, changeddramatically during th e fifty-ye ar period. While a single analysiscan be used if the changed d efinitions are entered as newvariables, interpretation is problematic. Th erefore , fou r sepa-rate successive analyses of the adoption of municipal civilservice reform we re conducte d (see Williamson, and Swanson,1966, fo r a similar resolution of the problem).

In the first analysis, the e ffe cts of the independent variables, asmeasured in the 1890 Census, on the trans ition rates for citiesadopting civil service measures b etwe en 1885 and 1904 were

examined. During this timespan only a small proportion of cities(about 11 percent) formally contracted with a commission orboard to set standardized personnel requirem ents for municipalemp loyees. Similarly, in the second analysis, the effe cts of citycharacteristics (measured ten years later) on the rate of adop-tion be twe en 1905 and 1914 we re again examined ; citiesadopting the m easure in the previous period were e xcludedfrom the analysis. This procedure was repeated for the thirdand fourth analyses, of rates of adoption betw een 1915 and1924, and between 1925 and 1934. In each analysis, citycharacteristics as measured in the decade just preceding th eadoption period wer e used as predictors. Our objective, then,

was to assess the continued effectiveness of these charac-teristics in predicting the rate of adoption over time.

Findings

The results of the analyses are presented in Table 2. For eachindependent variable, the top row shows the parameter esti-mates, the second row the standard errors of the coefficients,and th e third ro w the expo nential raised to the po wer of thecoe fficient. This last row indicates the proportion of change inth e adop tion rate induced by a change of t he predictor variableby one unit. W he n a variable has no effe ct, this value is 1.0. A

value greater than unity indicates a positive effect; less thanunity indicates a negative effect. For example, 1.1 indicates a 10percent increase in the adoption rate, whil e .9 indicates a 10percent decrease per unit change.

33/ASQ, March 1983

Copyright © 1983. All rights reserved.

7/27/2019 Tolbert e Zucker 1983

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/tolbert-e-zucker-1983 14/19

r t iona l Hazards Mod e l o f C iv i l Serv ice Ad opt io n over T im e , 1 885 -19 35

Percentage Manufactur ingfore ign- Percentage wag e Municipa l Logborn i l l i terate earnerst expen diturest size Age -2 log 1

Mode lchi-square

Mode lD

= 83)

= 74)

= 39)

BSEexp(B)

BSEexp(B)

BSEexp(B)

BSEexp (B)

. 1 1 4 ' "

.0401.120

. 0 5 6 "

.0271.058

.029

.0301.029

.021

.0401.020

*

- . 069.079.933

- . 2 7 9 ".127.757

- .006.171.994

- . 4 0 6 * ".888.666

- .070.550.932

.569

.8631.766

- .296.742.744

-1,657.910.191

.034

.6611.035

.2991.2671.349

-1.3611.734

.256

.487*

.3261.627

.383*

.2491.467

.325

.4281.384

- .766.651.465

.009

.0161.009

.0001

.0081.000

.016

.0131.016

- .010.016.990

63.27

175.67

104.07

57.25

15.52(p < .008)

15.77(p < .02)

10.38(p < .11)

2.04(p < .50)

.5 1

.3 5

.3 5

.1 7

< . 0 1 ; " p < . 0 5 ; * " p < . 1 0ess i ve m iss ing da ta ; no re li ab le es t ima te poss ib le .

ua l i ze d on c i ty s i ze .

obtainedontinuous version of th e depen-

ear of adoption) th at

ed an even more striking decrease

How ever , w e are less in te res ted in the e f f ec t s o f spec i f icvar iables than in the overal l f i t o f the model conta in ing the

var iables in combinat ion, s ince h is tor ians general ly ident i fy

these as a c luster and s ince they might be expected to in teractw it h each oth er. Harre l l (1979) has argued tha t the D stat is t ic

can be in terpreted analogously as the more famil iar /?2, but this

in te rpre ta t ion is no t w ide sprea d. Consequent ly , we focus on

th e chi-square stat is t ic and i ts s igni f ican ce level; bo th stat is t ics,however, lead to the same conclus ion.

Th e data provide strong sup port for our predict io ns. In th e f i rs t

per iod, the overal l model ch i-square is s igni f icant beyond the.01 level (p < .008). In th e sec ond p er iod, th e ef fe cts appear to

be wea ker, as th e overal l s igni f icance level is low er and f ew er

of the independent var iables have s ignif icant coeff ic ients. Thepredict ive p ow er of th e var iables as a group con t inues to

weaken through the th ird per iod and drops very sharply in thefou rth per iod. Th e in it ia l good explanat ion and the steep decl ine

in explanatory power in the last t ime per iod are consistent withour expectat ions. As the process of adopt ion cont inues, the

charac ter is t ics of c i t ies becom e increasingly less re levant to th e

adopt ion p rocess .6

I t is clear from the effects of the individual city variablesreported in Table 2 that t he de cis ion to adopt in th e ear ly t i m e

periods wa s based to a signif icant degree on those character is-t ics h is tor ians have descr ibed as important predictors of adop-

t ion of c iv il serv ice proced ures, tho se re lated to reducingconf l ic t and to stream lin ing the in ternal funct io ning of c i ty

gover nme nt . In bo th th e f i rs t and second t ime per iods, the

percentage of fore ign-born and c i ty s ize exerted s ignif icantin f luence on the adopt ion process in the expected d irect ion.

Also as pred icted, in th e f i rs t t im e per iod middle-c lass c i t ies(those with a smal ler proport ion of b lue-col lar workers), were

mo re l ike ly to adopt the re for m . Ho we ver, as th e process of

adopt ion cont inued, the character is t ics of c i t ies were lessfrequent ly s igni f icant predictors of adopt ion. Only one var iable,

th e percen tage of i l l i terates, eme rge d as s ignif icant in th e th ir dt im e per iod ; no var iables we re s ignif icant in th e last t im e per iod.

3 4 / A S Q , M a r c h 1 9 8 3

Copyr igh t © 1983 . A ll r igh ts reserve d .

7/27/2019 Tolbert e Zucker 1983

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/tolbert-e-zucker-1983 15/19

Diffusion of C ivil Service

Table 3

Mea ns and Sta nda rd Dev iations of City Characteristics over

PercentageTime fore ign-per iod born

1885-1904(A/ = 83) (

1905-1914(N = 74) (

1915-1924(W = 52) (

1925-1934(N = 39) (

•Standard deviatResidualizedor• M issing data.

21721173)

17671066)

15771192)

13321216)

Percentageil l i terate

*

6.9025(4.8043)

5.4500

(3.2914)

4.8809(2.7061)

tions in parenthese s.I city size.

Manufactur ingwageearnerst

- .0075(.4487)

- .0096(.4614)

.0399(.5637)

- .0288(.6031)

Time, 1885-1935*

Munic ipa lexpendi turest

- .0000(.3818)

- .0116(.3968)

- .0653(.3165)

- .0417(.3085)

Logsize

3.8581

(1.072)

3.9973(1.1049)

4.1660(.9712)

4.5989(.6721)

Age

1849.88(29.1994)

1849.71(30.4510)

1850.19(31.4503)

1847.76(33.1720)

Proport ionadopt ing

.0968(.2973)

.2976(.4600)

.2881(.4568)

.1905(.3974)

A major comp eting interpretation of th e results can be elimi-nated by examining the changes in variance ov er tim e in citycharacteristics. It is clear from Table 3 tha t the variance doesnot decrease systema tically over time.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Our hypotheses concerning the changing sources of formalstructure received considerable support in all analyses carriedout here. Civil service procedures we re adopted m uch morerapidly by cities wh en t he s tate mandated them and theprocess of adoption was directed by a single source. In contrast,w he n no state-level legitimation occurred, civil service proce-dures were adopted gradually, diffusing largely throu gh socialinfluence among cities. M ost im portant for organizationaltheory , ho weve r, are the findings that internal organizationalfactors predicted adoption of civil service procedures at th ebeginning of th e d iffusion process, but did not predict adoptiononce the process was well underwa y. As an increasing num berof organizations adopt a program or policy, it becomes progres-sively institutionalized, or wide ly understood to be a necessarycomponent of rationalized organizational structure. The legiti-macy of the procedures them selve s serves as the impetus forth e later adopters. These findings p ermit a partial integration of

the generally conflicting approaches focusing on the internal orthe institutional sources of formal s tructure. In addition, theyreassert the critical role of history for understanding organiza-tional structure and its change (Stinchcombe, 1965; Me yera ndBrown, 1977).

The results reported here also have implications for tw o majorareas of research that we did not directly address. First,treatme nt of the spread of innovation in a general theoreticalframework permits the researcher both to gain more insightsinto the processes at work and to obtain more precise specifica-tion of expected difference s in patterns, rates, and correlates o f

dif fusion. The ad hoc quality of m ost diffus ion s tudies (e.g.,Brow n and Philliber, 1977) has made cumulative developm entnearly impossible except when the substantive diffusion isexactly th e same, like the d iffusion of hybrid corn, as discussedby Feller (1967). In contrast, w e expec t tha t our model can be

35/ASQ, March 1983

Copyright © 1983. All rights reserved.

7/27/2019 Tolbert e Zucker 1983

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/tolbert-e-zucker-1983 16/19

app l ied to a w ide range o f phe nom ena . For exam ple , w he n

dif fus ion patterns are suddenly truncated ear ly in the process,

w e e xpec t tha t there w as a fa i lu re to leg i t imate the chang e and

the character is t ics that in i t ia l ly predicted adopt ion wi l l remain

good pred ic to rs th roughout the p rocess . In fac t , th is may we l l

exp la in the pa t te rn o f the d i f fus ion o f some innovat ions in

educat ion , tho ug h the ava i lab le da ta a re no t su f f ic ien t fo ra tes t

(Rowan, 1982).

Second , the resu l ts have imp l ica t ions fo r methodo logy . Theuse o f c ross-sec t iona l da ta and the me asu rem ent o f c i ty

character is t ics with avai lable data, not f rom the h is tor ica l per iod

under invest igat ion, has been customary in research on the

adopt ion o f mun ic ipa l re fo rms by c ity gov ernm ents (c f. , Sher-

benou , 196 1 ; Kesse l, 1962 ; Sch no re and A l fo rd , 1963; Wo l -

f in ge ran d Fie ld, 196 6; L ineberry and Fowler, 1967). Th e resu lts

repor ted here shou ld m ake it c lear tha t such metho do log ica l

sho r tcom ings may in t roduce ser ious b iases in to the da ta : (1)

these s tud ies o f mun ic ipa l re fo rm neg lec t the fac t tha t con-

temporary data may not accurate ly ref lect the c i ty 's s tanding on

var ious charac te r is t ics a t the t im e the re fo rm w as ac tua lly

adop ted and, thu s , it is d i f f icu l t to be cer ta in w he th er p resent -

d ay d i f fe r e n c e s b e t w e e n " r e f o r m e d " a n d " u n r e f o r m e d " c it ie s

are causal ly or consequent ia l ly re lated to the adopt ion of the

reforms, and (2) these studies, by re ly ing on cross-sect ional

des igns , ignore the fac t tha t adopt ion o f re fo rm s by c i t ies

occurred over t im e and tha t fac to rs in f luen c ing adopt ion may

have var ied from one point in t ime to the next. A c i ty charac-

ter is t ic important in predict ing ear ly adopt ion may be ir re levant

twenty years la te r .

Thus , th e approach and resu lts p resente d here have imp l ica-

t ions , bo th theore t ica l and methodo log ica l , fo r s tud ies o f

change in the formal s tructure of organizat ions, for s tudies ofinnovat ion and d i f fus ion , and fo r s tud ies o f adopt ion o f re fo rm s

by mun ic ipa l gov ernm ents . Bu t , mo st s ign i f ican t in te rm s o f th e

goals of our research, the boundar ies between the rat ional and

the ins t i tu t iona l approaches to o rgan iza t ions have been mo re

clear ly spe cif ie d and th e centra l ro le of h is tory in und erstan ding

organ izat ions con f i rm ed. An adopt ion p rocess roo ted in the

internal needs of the organizat ion can become over t ime a

process roo ted in con form i ty to ins t i tu tiona l de f in i t ion .

Organizations and Environ-ments. E nglewood C liffs, NJ:Prentice-Hall.

rd, and Jeffrey Pfeffer

tions ." In A. Inkeles, J. Cole-man, and N. Smelser (eds.),Annual Review of Sociology, 2:79-105. Palo Alto, CA: AnnualReviews.

Theodore, and Seym our

"Orga nizational size and func -tional com plexity: A study ofadministration in hos pitals."American Sociological Review,26 : 23 -28 .

Benson, J. Kenneth1975 "T he interorganizational net-

wo rk as a political econ om y."Administrative Science Quar-terly, 20: 229-249.

Berger, Peter, and Thom asLuckmann1967 The Social Construc tion of Real-

ity. New York: Doubleday.

Blau, Peter M .1970 "A form al theory of differentia-

tion in organization." AmericanSociological Review, 35:201 -218.

Blau, Peter M., and Richard A.Schoenherr1971 The Structure of Organizations.

New York: Basic Books.

Brown, Lawrence A., and Susan G.Philliber1977 "The diffusion of a population-

related innovation: The plannedparenthood affiliate." SocialScience Quarterly, 58: 215-228.

Carroll, Glenn R.1982 Dynam ic Analysis of Discrete

Dependent Variables: A Didac-tic Essay. Ma nnhe im, Ger-many: Zentrum fur Umfragen,Method en und Analysen.

36/ASQ, March 1983

Copyright © 1983. All rights reserved.

7/27/2019 Tolbert e Zucker 1983

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/tolbert-e-zucker-1983 17/19

Diffusion of Civil S ervice

Carrol l , Glenn R., and JacquesDelacroix1982 "Organizational mortality in the

newspaper industries of Argen-tina and Ireland: An ecologicalapproach." Administrative Sci-ence Quarterly, 27: 169-198.

Chi ld, J .1972 "Organization structure, envi-

ronment, and performance —

The role of strategic choice."Sociology, 6: 1-22.

Cl inton, Spencer1886 "R efo rm in municipal govern-

me nt. " Papers read before TheCleveland Democracy of Buf-

falo (Buffalo): 101-116.

Coleman, James S.1964 Introduction to Mathematical

Sociology. Ne w York: FreePress.

Cox , D. R.1972 "Regress ion models and life

tables ." Journal of th e RoyalStatistical Society, 34: 187-220.

Crandon, Frank P.1886 -1887 "Misg ovem men t of

great cities." PopularScience Monthly, 30:521-524.

Cyert, Richard, and Jam es G. March1963 Behavioral Theory of the Firm.

New York: Free Press.

DiPrete, Thoma s1981 "Unem ploymen t over the l i fe

cycle: Racial differences andthe effects of changing eco-nomic conditions." AmericanJournal of Sociology, 87: 286-307.

Dow ns, George, and LaurenceM o h r1976 "Concep tual issues in the study

of innovation." AdministrativeScience Quarterly, 21:700-714.

Feller, I rwin1967 "Approa ches to the diffusion

of inn ovations." Explorations in

Entrepreneurial History, 4:232-244.

Gelfand, Mark1975 A National Compe ndium of

Cities. New York: Oxford Uni-versity Press.

Gordon , Daniel1968 "Im mig rants and urban gov-

ernmental form in Americancities, 1933-60." AmericanJournal of Sociology, 74: 158 —171.

Gri f f i th, Ernest

1974 A History of America n CityGovernment: The ProgressiveYears and Their Aftermath,1900-1920. New York:Praeger

Ham bl in, Robert, I . B. Jacobsen,a n d J . L L M i l l e r1973 A Mathe matical Theory of So-

cial Change. New York: Wiley.

Hannan , Michael , Nancy B. Tum a,and Ly leGroeneve ld1978 "Incom e and independence ef-

fects on marital dissolution:Results fro m th e Seattle andDenver income-maintenanceexperiments." Am erican Jour-

nal of Sociology, 84: 611 -63 3.

Harrel l , Frank1979 "PH GL M Procedu re." SAS

Technical Report. Raleigh, NC:SAS Institute.

Hays, Samuel1964 "Politics of reform in the Pro-

gressive Era." Pacific North-west Quarterly, 55: 15 7-169.

1972 "T he new organizational soci-et y. " In Jerry Israel (ed.), Build-ing the Organizational Society:

Associational Tendencies inEarly Twen tieth-CenturyAmerica: 1-9. New York: FreePress.

Hemes , Gudmund1976 "St ructu ral change in social

processes." American Journalof Sociology, 82: 5 13-5 47.

Hofstadter, Richard1956 Age of Reform . New York:

Knopf.

Hopkins, Alan1981 "Regression w ith incomplete

survival data." BiomedicalStatistical Software. Berkeley,CA: University of CaliforniaPress.

Hug hes, Everett C.1936 ' Th e ecological aspects of in-

stitutions." American Sociolog-ical Review, 1: 180-189.

Kessel, John1962 "Gove rnmen tal structure and

political environment: A statis-tical note about A mericancities." American P olitical Sci-ence Review, 56: 615 -62 0.

Kimber ly, John1975 "Environm ental constraints and

organizational structure: Acomparative analysis of re-habilitation organizations."Administrative Science Quar-

terly, 20: 1-9.

Knoke, David1982 "T he spread of m unicipal re-

fo rm: Temporal, spatial, andsocial dynamics." AmericanJournal of Sociology, 87:1314-1339.

Liebert, Roland1976 Disintegration and Political Ac-

tion. New York: AcademicPress.

37/ASQ, March 1983

Copyright © 1983. All rights reserved.

Linebe rry, R. L , and E. P. Fowler1967 "Re form ism and public policies

in American citie s." Am ericanPolitical Science Review, 6 1 :701-716.

Maddala, G. S.1977 Econometrics. New York:

McGraw-Hill.

March, James G., and Johan P.

Olsen1976 Am biguit y and Choice in Or-ganizations. Oslo, Norway :Universitetforlaget.

Meyer, Joh n W., and Br ian R owan1977 "In stitutio nalize d organiza-

tions: Formal structure as mythand ceremony." AmericanJournal of Sociology, 83: 340-363.

Meyer, Mars hal l , and M. CraigBrown1977 ' 'The process of bureaucratiza-

t ion." American Journal ofSociology, 83: 364 -385 .

Parsons, Talcott1951 The Social System. New Y ork:

Free Press.

Pfeffer, Jeffrey1981 Pow er in Organizations.

Marshfield, MA: Pitman.

Pfeffer, Jeffrey , and G erald R.Salancik1978 The External Control of Organi-

zations. New York: Harper andRow.

Rogers, Everett M.1962 Diffusion of Innovations. NewYork: Free Press.

Rowan , Brian1982 "Orga nizational struc ture and

the institutional environment:The case of public sc hools ."Adm inistrative Science Quar-

terly, 27: 259-27 9.

Schiesl , Mart in1977 The Politics of E fficiency.

Berkeley, CA: University ofCalifornia Press.

Schnore, Leo, and Robert Al fo rd1963 "Form s of government andsocioeconomic characteristicsof suburbs." AdministrativeScience Quarterly, 8: 1 - 17 .

Scott, W. Richard1975 "Organizational struc ture. " In

Alex Inkeles (ed.), Annual Re-view of Sociology, 1: 1 -25 .Palo Alto, CA: A nnual Reviews.

Sherb enou, Edgar1961 "Cla ss, participation and the

council-manager plan." PublicAdministration R eview, 2 1 :

131-135.

7/27/2019 Tolbert e Zucker 1983

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/tolbert-e-zucker-1983 18/19

be, Arthu r L."Soc ial structu re and organiza-tions," In J. G. March (e d),Handbook of Organizations:142-193. Chicago: Rand Mc-Nally.

David P.2 The New Citizens hip: Origins

of Progressivism in Wiscons in,

1885-1900. Columbia, MO :University of Missouri Press.

7 Organizations in Ac tion. NewYork: McGraw-Hill.

rnto n, R., and P. M. Na rdi"T he dynamics of role acquisi-t ion." American Journal ofSociology, 80:870-885.

Invoking Rate. Stan ford, CA:Stanford University.

7 Organizations in Mod ern Life.San Francisco, CA: Joss ey-Bass.

1 "Th e process of technologicalinnovation in the f i rm."Adademy of ManagementJournal, 14 :75 -88 .

Van Riper, Paul1951 History of the United States

Civil Service. Evanston, IL:Row, P eterson.

Walker, Jack1969 "D iffus ion of innovations

among the American states."Am erican Political Science Re-view, 63: 880-899.

Weinste in, James1968 The Corporate Ideal in the Lib-

eral State. Boston: BeaconPress.

White, Morton G.1949 SocialT hough tin Ame rica: The

Revolt Against Formalism. NewYork: McGraw-Hill.

Wiebe, R obert1967 The Search for Order, 1 87 7-

1920. Ne w York: Hill and Wa ng.

Wil l iam son , Jeffrey G., and JosephA. Swanson

1966 "Th e grow th of cities in theAmerican Northeast, 1 82 0-1870." Explorations in Entre-preneurial History, 11 (Supple-ment). 1-101.

Wol f inger , Raymond, and JohnField1966 "Politica l ethos and the struc-

ture of city governm ents."Am erican Political Science Re-view, 60: 159-195.

Woodruff , Cl inton1903 "A n Am erican municipal pro-

gram." Political Science Quar-terly, 18: 47-5 8.

Woodward , Joan1965 Industrial Organization: Theory

and Practice. London: OxfordUniversity Press.

Zucker, Lynne G.

1977 "T he role of institutionalizationin cultural persistence." Am eri-can Sociological Review, 42:726-743.

1982 "Ins titutio nal structure and or-ganizational processes: Therole of evaluation units inschools." In Adrianne Bank andRichard C. Williams (eds.),Studies in Evaluation and Deci-sion Making. CSE MonographSeries in E valuation, No. 10:69-89 . Los Angeles, CA: Cen-ter for the Study of Evaluation.

1983 "Organizations as institutions ."In Samuel B. Bacharach (ed),Perspectives in OrganizationalSociology: Theory and Re-search. ASA Series, Vol. 2.Greenw ich, CT: JAI Press(forthcoming).

Zucker, Joel Steven1975 Pattern Discrimina tion Based

on an Exponential Error Crite-rion. Santa Monica, CA: RandCorporation.

APPENDIX: Data Sources

Civil Service Reform League. Civil Service Agencies in the United States: A7940 Census. Chicago: The Assembly, 1942.

Colum bia Lippincott Gaze tteer of the World. New Y ork: Lippincott, 1954.

Department of Labor. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Bulletin 30 (Table XVII):

997-999. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, 1900.National Municipal League. Proceedings of the Philadelphia Conference for

Good City Government and the First Annual Meeting of the N ational Municipal

League. Philadelphia: National Municipal League, 1894.

National Municipal League. Proceedings of the Milwaukee Conference forGood City Government and the Sixth Annual Meeting of the National MunicipalLeague. Philadelphia: National Municipal League, 1900.

National Municipal League. Proceedings of the New York Conference for GoodCity Government and the Eleventh Annual Meeting of the National MunicipalLeague. Philadelphia: National Municipal League, 1905.

National Municipal League. Proceedings of the C incinnati Conference for GoodCity Government and the Fifteenth Annual Meeting of the National MunicipalLeague. Philadelphia: National Municipal League, 1909.

National Municipal League. National Municipal Review. Concord, NH: RumfordPress, 1915.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. Compendium of the Tenth Census. Part 1, TableXXVI: 452^ 163; Table XXXVI: 860-909. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of theCensus, 1880.

38/ASQ, March 1983

Copyright © 1983. All rights reserved.

7/27/2019 Tolbert e Zucker 1983

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/tolbert-e-zucker-1983 19/19

Diffusion of Civil Service

U.S. Bureau of th e Census. Report on V aluation, Taxation and Public Indebted-ness. Table IV: 248-261 . Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census. 1880.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. Comp endium of the Eleventh Census. Part 3, Table3: 31 7-31 8; Table 95: 570-571 . Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census,1890.

U.S. Bureau of the Census . Report on W ealth, Debt and Taxation. Part 2, Table12: 55 6-5 57 ; Table 14: 580-5 99. Wa shington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census,1890.

U.S. Bureau of the Census Ab stra cto r the Twelfth Census. Tab le85 :115-117 ;

Table 88: 124 -129 . Wash ington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1900.U.S. Bureau of the Census. Manufacturers. Part 2, Table 2: 992 -100 5.Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1900.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. Population. Part 1, Table L: C IX-CX. W ashington,DC : U.S. Bureau of the C ensus, 1900.

U.S. Bureau of the Census Abstract of the Thirteenth Census. Table 19:9 5 - 9 6 ; Tables 33 -3 4: 250 -25 3. Wa shington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census,1910.

U.S. Bureau of the Censu s. Financial Statistics of Cities Having a Population ofover 30,000. Table 3: 118-119. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census,1910.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. Population. Tables III and IV: 152-291. Washington,DC : U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1910.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. FinancialStatistics of Cities Having a Population ofover 30,000. Table 3: 96-111 . Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census,1919.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. Abstract of the Fourteenth Census.Tables 31 - 4 3 :110-117; Tables 139-141 : 441 -44 5. W ashington, DC: U.S. Bureau of th eCensus, 1920.

U.S. Bureau of th e Census. Manufacturers. Tables by state. Wash ington, DC:U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1920.

U.S. Bureau of th e Censu s. Population. Table 18: 130-131 ; Table 20 : 240-335.Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1920.

U.S. Bureau of the C ensus. Manufacturers. Part 3, Table 2 (for each s tate).Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1929.

U.S. Bureau of the Cen sus. Abstract of the Fifteenth Census. Tables 43 -4 8:101 -11 2; Tables 144 -146: 284-291 . Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of theCensus, 1930.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. Financial Statistics of CitiesHaving a Population ofover30,000. Tab le4: 199-2 25. Was hington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census,1930.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. Population. Table 8: 21 ; Table 57: 1 00-10 3.

Washington, DC; U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1930.

U.S. Bureau of the C ensus. Population. Part 1, Table 13: 34 -3 6; Table 64:

160 -165 . Washington, D C: U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1940.