travel Gegen die Wand: Die Griechenland Kreativen … · We pay a visit to a city that is ......

Transcript of travel Gegen die Wand: Die Griechenland Kreativen … · We pay a visit to a city that is ......

Lufthansa Magazin 8/201532

travelGriechenland

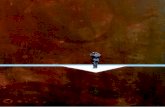

Against the wall: Art-ists portray Greece’s present plight on the streets of this city

Gegen die Wand: Die Kreativen erobern den städtischen Raum auch mit Street-Art

32_LHM_Hellas_neue_Helden.indd 32 06.07.15 13:13

Fotos Yadid Levy

Greek heroes of our timeWhile Greece groans beneath the weight of the debt crisis, most Greeks remain buoyant – especially in Thessaloniki, an ancient port that is now a buzzing creative center. We pay a visit to a city that is crafting its own future

Text Mathias Becker

Neue Helden für HellasGriechenland ächzt unter der Schuldenkrise. Aber unterkriegen lässt sich kaum einer. Erst recht nicht in Thessaloniki, der alten Hafenstadt, die jetzt Kreativzentrum wird. Besuch in einer Stadt mit Zukunft

32_LHM_Hellas_neue_Helden.indd 33 06.07.15 13:14

Thessaloniki has become a symbol of hope

Die Stadt ist zum Symbol geworden für die Hoffnung

34 Lufthansa Magazin 8/2015

travelGriechenland

At Nea Folia (left), innkeepers Dimitris Pardalidis and George Chlouzas serve pork with strawberry sorbet and kiwi (above) and other Greek-Oriental creations. A couple takes a stroll along Nikis Street (below), parts of which are for pedestrians only

In der Taverne Nea Folia (links) servieren Dimitris Pardalidis und George Chlouzas griechisch-orientalische Küche, darunter Schwein an Erdbeersorbet und Kiwi (oben). Lässiges Flanieren in der Nikis-Straße, die zeitweilig zur Fußgängerzone wird (unten)

32_LHM_Hellas_neue_Helden.indd 34 06.07.15 13:14

He promised me a library, but all I find here in the old harbor of Thessaloniki is a large, burgundy-colored plastic tub upended on four stilts and with the words “Think Tank” emblazoned on its side. Dimitris Theodorakos, 27, is responsible for its construction. He ducks his head and disappears down to his shoulders. I fol-low. Straightening up, I find myself surrounded by books – refer-ence works, novels. “Anyone who puts a book in here can take one out,” says Theodorakis. Although an economics student, he doesn’t believe that his country’s crisis can be solved in a semi-nar room – or on the street, either, which is why he joined Thessa-loniki Next2U, a group of activistis who want to change their city. One time they gave its shabby bus stops a colorful coat of paint, another time they organized food for the poor. Their latest deed: setting up the Think Tank library. “We want to be a living example of community culture,” says Theodorakos. Sticking together, now of all times, that is Thessaloniki Next2U’s message.

No city in Greece is as much a symbol of hope for a better future as Thessaloniki. The country is suffering from sanctions and austerity measures, but right here, startups are popping out of the ground like mushrooms beside design firms and delicates-sen factories, hiprestaurants and action groups. In these desper-ate times, the people of Thessaloniki, indeed people throughout much of Macedonia, are boldly following their own ideas – and putting them into practise. Of course poverty and unemployment exist here. “But we don’t take it as hard as the Athenians,” ex-plains one taxi driver, who sets some of his sparse earnings aside to pay for his daugher’s piano lessons, “and we seek solutions.”

I leave the old harbor behind and follow the broad prome-nade that today belongs to people out for a stroll, street traders and musicians. The city’s new government has introduced car-free Sundays, once a month to start with, but there are thoughts of banning motorized traffic from the boulevard entirely. This would no doubt please the many young couples out walking, holding hands. At White Tower, the city’s famous landmark, I sit on the wharf dangling my feet and watch the big ships plowing the hori-zon. Ever since it was founded in 315 B.C.C., Thessaloniki has been an important Mediterranean port. Roman and Byzantine rule in this region was followed by almost 500 years under the Otto-mans. In 1912, it went to the Greeks. Fifteen buildings in Thessa-loniki are UNESCO World Heritage sites and testify to the region’s checkered history.

A droning bass beat awakens me from my daydreams. Close by, young people are dancing in the sun to electronic music. Of the city’s 400 000 inhabitants, 120 000 are students – a larger percentage than in any other southeast European city. All anyone needs to start an impromptu party here is a good sound system; the rest will follow. The many young people are one reason for the upswing; they bring creative potential to the city. All the same, the most important force for renewal is an elderly gentleman: Yian-nis Boutaris, 72, mayor of Thessaloniki since 2011. Dressed in rainbow-striped suspenders, wearing metal-rimmed glasses and sporting tattoos, the ex-winegrower and ex-alcoholic looks the very antithesis of the political establishment. While his pre-

E ine Bibliothek hatte Dimitris Theodorakos mir versprochen. Nun stehe ich im alten Hafen von Thessaloniki vor einem großen weinroten Plastikbottich, der kopfüber auf vier Stel-

zen thront. „Think Tank“ steht darauf geschrieben. Theodorakos hat die Konstruktion hier aufgestellt, er zieht den Kopf ein und verschwindet schulteraufwärts darunter. Ich folge ihm. Als ich mich aufrichte, bin ich von Buchrücken umgeben. Sachbücher, Romane: „Wer ein Buch hineinstellt, darf sich eins nehmen“, sagt Theodorakos. Der 27-Jährige, Kapuzenjacke und Turnschuhe, studiert Wirtschaft, findet aber, dass die Krise seines Landes nicht im Seminarraum zu lösen ist, sondern auf der Straße. Deshalb hat er sich „Thessaloniki Next2U“ angeschlossen, einer Aktivisten-gruppe, die ihre Stadt verändern will. Einmal haben sie schäbige Bushaltestellen bunt angepinselt, später eine Tafel für Bedürftige gegründet. Jüngstes Werk: die Bottich-Bibliothek. „Wir wollen eine Kultur des Miteinander vorleben“, sagt Theodorakos. Zusammenhalten, gerade jetzt, das ist die Botschaft.

Keine Stadt in Griechenland steht so sehr für die Hoffnung auf eine bessere Zukunft wie Thessaloniki. Das Land ächzt und stöhnt unter Sanktionen und Sparzwang, aber hier schießen Start-ups wie Pilze aus dem Boden. Designbüros und Feinkostmanufak-turen, szenige Restaurants und Bürgergruppen. In einer Zeit der Hoffnungslosigkeit wagt man etwas in Thessaloniki, zeigt das Volk beinahe in der ganzen Region Makedonien den Mut zur eigenen Idee – und zur Tat. Natürlich gibt es auch hier Armut und Arbeits-losigkeit. „Aber wir sind gelassener als die Athener“, erklärt mir ein Taxifahrer, der sich den Klavierunterricht seiner Tochter vom schmalen Einkommen abspart, „und wir suchen nach Lösungen.“

Ich lasse den alten Hafen hinter mir und folge der breiten Uferstraße, die heute Flaneuren, Händlern und Straßenmusikern gehört. Die neue Stadtregierung hat den autofreien Sonntag ein-geführt, zunächst einmal im Monat, aber schon wird überlegt, die Autos ganz vom Boulevard zu verbannen. Die Liebenden würd’s freuen, überall sind händchenhaltende Pärchen unterwegs, die könnten dann flüstern. Am Weißen Turm, dem Wahrzeichen der Stadt, lasse ich die Füße von der Kaimauer baumeln und schaue den großen Pötten am Horizont hinterher. Seit seiner Gründung 315 vor Christus ist Thessaloniki eine der wichtigsten Hafenstäd-te des Mittelmeers. Nach Römern und Byzantinern herrschten fast 500 Jahre lang die Osmanen über diesen Landstrich. 1912 ging er an die Griechen. Von der bewegten Geschichte zeugen 15 Bauten, die zum Unesco-Weltkulturerbe zählen.

Ein Basshämmern holt mich aus den Tagträumen. Nicht weit entfernt tanzen junge Leute in der Sonne zu elektronischer Musik. Von den 400 000 Einwohnern der Stadt sind 120 000 Studenten – prozentual mehr als in irgendeiner anderen südosteuropäischen Stadt. Wer spontan eine Party starten will, braucht nur eine gute Musikanlage, der Rest ergibt sich. Die vielen Jungen sind ein Grund für den Aufschwung, mit ihnen kommt das kreative Potenzial in die Stadt. Der wichtigste Erneuerer ist gleichwohl ein älterer Herr: Giannis Boutaris, 72, seit 2011 Bürgermeister von Thessaloniki, auch wenn er auf den ersten Blick nicht so aussieht. Bunte Hosenträger und Nickelbrille, dazu Tätowierungen

35

32_LHM_Hellas_neue_Helden.indd 35 26.06.15 11:16

decessors, convicted of corruption, sit out their prison sen-tences, Boutaris, who never belonged to a major political party, is now celebrated like a guru, which is why the muscle outside his office is there mainly to stop fans from storming in.

Once we are sitting across from each other, Boutaris fishes a filterless cigarette our of his breast pocket, lights up and starts talking almost reverently about how he had to drastically reorga-nize the city government in order to achieve anything at all; about the car-free Sundays on the promenade and the newly introduced recycling system. One of his first projects, though, was to intro-duce measures to preserve the city’s cultural heritage. He culti-vates good relations with the Turks, whose state founder, Kemal Atatürk, was born in Thessaloniki. He also initiated a march to preserve the memory of hundreds of thousands of Jews deported during World War II. Thessaloniki was once home to one of the largest Jewish communities in Europe. Boutaris says: “We can only build the future on the knowledge of the past.” In this case, it even applies quite specifically: The number of tourists from Israel and Turkey has risen drastically in a very short time. Among the tattoos on his right hand, Boutaris has a lizard, which, he says, reminds him that any crisis can be overcome. “The animal stands for new beginnings because it can shed its skin.” A lot more people in Thessaloniki deserve a lizard tattoo, I muse. Athanasios Babalis, for example. The 52-year-old product designer who lived for many years in London and New York and won numerous major awards before returning to his native city. Today, he enjoys

auf den Händen: Der Ex-Winzer und Ex-Trinker ist die Anti-these zum politischen Establishment. Während sein Vorgänger wegen Untreue im Gefängnis sitzt, wird Boutaris, der keiner großen Partei angehört, gefeiert wie ein Guru.

Und so sind die bulligen Kerle vor seinem Büro in erster Li-nie dafür zuständig, dass keine Fans hereinstürmen. Als wir uns gegenübersitzen, angelt Boutaris eine Filterlose aus der Hemd-tasche, steckt sie an und beginnt fast andächtig zu erzählen. Dass er die Verwaltung umkrempeln musste, um überhaupt et-was umsetzen zu können – vom autofreien Sonntag an der Pro-menade bis zum neu eingeführten Recycling. Eines seiner ersten Projekte aber war die Pflege des kulturellen Erbes der Stadt. Er kümmert sich um gute Beziehungen zu den Türken, deren Staats-gründer Kemal Atatürk in Thessaloniki geboren wurde. Er initiierte einen Marsch zum Gedenken an die Deportation Hunderttausen-der Juden während des Zweiten Weltkriegs. In Thessaloniki war einst eine der größten jüdischen Gemeinden Europas zu Hause. Boutaris sagt: „Nur wenn wir die Vergangenheit kennen, können wir die Zukunft bauen.“ In diesem Fall funktioniert das sogar ganz konkret: Die Zahl der Touristen aus Israel und der Türkei ist in kur-zer Zeit drastisch gestiegen. Unter Boutaris’ Tätowierungen, auf der rechten Hand, ist auch eine Echse. Sie soll ihn, sagt er, daran erinnern, dass jede Krise überwunden werden kann. „Das Tier steht für den Neuanfang, weil es sich häuten kann.“

In Thessaloniki könnten sich viel mehr Menschen die Echse tätowieren lassen, denke ich. Athanasios Babalis zum Beispiel.

36 Lufthansa Magazin 8/2015

travelGriechenland

[e][d]

Giorgos Zongolopoulos’ sculpture “Umbrellas” (left). Clean lines and great drinks at the Met Hotel (below)

Yiannis Boutaris: radical thinker and respected mayor

Giorgos Zongolopoulos’ Skulptur „Regenschirme“ (links). Die Bar im Met Hotel verbindet klares Design mit famosen Drinks (unten)

Aufräumer: Bürgermeister Giannis Boutaris

32_LHM_Hellas_neue_Helden.indd 36 08.07.15 08:44

the quiet life here – and is happy to be a part of the boom-ing creative industry. Design firms like 157 + 173 and Beetroot are just two overnight success stories that enjoy international recog-nition. Aliki Tsirliagkou has just opened the Nitra Gallery right next door to Babalis’ studio and shows contemporary art from the re-gions that have informed the city – Greece, Turkey and the Balkan states. “The city is undergoing change,” says Tsirliagkou elatedly, “suddenly, experiments are possible here.”

One experiment was made by the brothers Thomás und George Doúzis, who have been marketing Greek delicatessen specialties since 2008. “We wanted to show the world that we have more to offer than souvlaki,” says George. Now their product range has become so extensive they recently had to move to a new store providing 1000 square meters of space. Another success story is that of Dimitris Pardalidis and George Chlouzas, who a few years ago restored the empty tavern now called “Nea Folia,” where they serve Mediterranean fare with an oriental touch – which tastes great! A few streets away at the Estrella, Kostas Kapetanakis sells a confection of his own creation: bougatsan. It’s a croissant filled with the sweet vanilla cream that usually goes into traditional Greek pastries. The result looks just as good as it tastes. Photos of the pastry went viral on Instagram and over-night, Kapetanakis, who had lost his job in 2011, became the king of street food. He is just one of Hellas’ new heroes, who can be found on every street corner in Thessaloniki.

The people of Thessaloniki are incorrigible traditionalists in one regard: On days off from work, they all head to Chalkidiki Peninsula, south of the city, which resembles a three-fingered hand reaching into the Aegean. I follow their lead and drive out between cornfields and olive groves toward the sea. Halfway there, I come to the village of Nea Gonia, where Marianna

Gorgeous in white: Portokali Beach and, of course, the bride

“The city is undergoing change, and experiments are possible”

Der 52-jährige Produktdesigner hat viele Jahre in London und New York gelebt und wurde mit zahlreichen wichtigen Prei-sen ausgezeichnet, ehe er in seine Heimatstadt zurückkehrte. Heute genießt er das gelassene Leben hier – und ist glücklich, Teil der boomenden Kreativbranche zu sein. Designbüros wie „157 + 173“ oder „Beetroot“ gehören zu international geachteten Senkrecht startern. Und gleich neben Babalis’ Atelier hat Aliki Tsir-liagkou die Galerie „Nitra“ eröffnet. Ausgestellt wird Gegenwarts-kunst aus den Regionen, die den Ort geprägt haben, aus Grie-chenland, aus dem Balkan, aus der Türkei. „Die Stadt befindet sich im Wandel“, sagt Tsirliagkou beschwingt, „plötzlich sind hier Experimente möglich.“

Eines davon haben die Brüder Thomás und George Doúzis gestartet, seit 2008 vermarkten sie griechische Feinkost. „Wir wollten der Welt zeigen, dass unsere Küche mehr bietet als nur Souvlaki“, sagt George. Mittlerweile ist ihr Sortiment so umfang-reich geworden, dass sie vor Kurzem umziehen mussten, jetzt residieren sie auf einer Ladenfläche von 1000 Quadratmetern. Oder, noch so eine Erfolgsstory, Dimitris Pardalidis und George Chlouzas, die vor einigen Jahren eine leer stehende Taverne auf-polierten. Heute servieren sie im Nea Folia mediterrane Küche mit orientalischen Einflüssen – exzellent! Ein paar Straßen weiter verkauft Kostas Kapetanakis im Estrella seine eigene Erfindung: Das Bougatsan ist ein Croissant, gefüllt mit einer süßen

Ein Traum in Weiß: der Portokali Beach – und die Braut natürlich auch

„Thessaloniki befindet sich im Wandel, hier sind Experimente möglich“

Aliki Tsirliagkou, Galeristin/gallery owner

3737

[e]

[d]

32_LHM_Hellas_neue_Helden.indd 37 06.07.15 13:15

Idyllic: Sithonia’s sandstone coast beside azure waters

Idyll in Blau: die Sandsteinküste von Sithonia

38

travelGriechenland

32_LHM_Hellas_neue_Helden.indd 38 30.06.15 13:14

“We can only build the future on our knowledge of the past”

„Wer die Vergangenheit kennt, kann an der Zukunft bauen“

Giannis Boutaris, Bürgermeister von Thessaloniki Yiannis Boutaris, mayor of Thessaloniki

32_LHM_Hellas_neue_Helden.indd 39 30.06.15 13:14

Greece

Kazakis is expecting me. Her name is indelibly associated with dolmadakia, vine leaves with all manner of stuffings. “The market for our grapes collapsed during the Balkan wars,” she tells me, “so we had to improvise.” They began producing grape jam and raisins, but mostly stuffed vine leaves, which became an ex-port hit. Her small factory turns out around 12 000 dolmadakia ev-ery day. Macedonian products are in great demand. “All we need now is a Tuscan image,” says Kazakis, “but we’re working on it.”

Back in my car, I can hardly decide where to go next. Every-one I asked told me a different best place, so in the end, I visit them one after another, the quaint villages and sleepy coves on Kassandra and Sithonia, the western and middle fingers, passing aromatic pinewoods, rugged cliffs, brightly colored beehives and snow-white shrines. Herds of goats keep forcing me to slow to walking pace – and that’s actually good because if you drive too fast here, you are likely to miss the track down to the next mag-nificent beach. At Portokali Beach, where the sand is especial-ly white and the sea a radiant turquoise, I stumble on a wedding party: a Dutch couple, barefoot beneath the bright blue sky, tak-ing their vows before two dozen guests. For me, this sight makes up entirely for the fact that I will not be seeing the eastern finger, Athos, on this trip – because obtaining the visa to visit the monks who live there takes weeks. Women are not even allowed into the monks’ republic. Those who had the honor of staying with the monks return enthusing about inner reflection and pristine natural surroundings.

In the evening, I eat on the terrace of an old stone house with a fantastic view of the sea, a former farm laborers’ shelter that has been in the Koufadakis family for generations. It’s 12 years since they opened the Mpoukadoura, one of the best restaurants hereabouts. As owner Yiota Koufadakis serves my rock samphire salad, she points out a pine high on a rock. “That tree is 64 – the same age as me,” she says. “It has survived wind, weather and all the seawater in the ground.“ My plate is emply, the sun set long ago and only now do I realize what Yiota meant: She wasn’t just talking about the pine, she was talking about the hope for change – and all of Greece.

Vanillecreme, die eigentlich in ein traditionelles griechisches Gebäck gehört. Das Ergebnis sieht so gut aus, wie es schmeckt. In rasender Geschwindigkeit haben sich Bilder der Süßspeise über die Foto-Plattform Instagram verbreitet – und Kapetanakis, der 2011 seinen Job verloren hatte, wurde über Nacht zum Street-food-König. Hellas’ neue Helden, man findet sie in Thessaloniki an jeder Straßenecke.

Nur in einer Frage sind seine Bewohner unverbesserliche Tra-ditionalisten: An ihren freien Tagen steuern sie alle die Halb insel Chalkidiki an, die südlich der Stadt wie eine Hand mit drei Fingern in die Ägäis ragt. Ich folge ihnen allen, setze mich in ein Auto, rolle zwischen Kornfeldern und Olivenhainen Richtung Meer. Auf hal-bem Weg erreiche ich das Dorf Nea Gonia, wo mich Marianna Ka-zakis erwartet. Ihr Name steht im ganzen Land für dolmadakia, ge-füllte Weinblätter. „Während der Balkankriege brach uns der Markt für Tafeltrauben weg“, erzählt sie, „also mussten wir improvisie-ren.“ Sie produzierten Traubenmarmelade und Rosinen, vor allem aber gefüllte Weinblätter, ein Exportschlager: Rund 12 000 Stück werden täglich in der kleinen Manufaktur gefertigt. Makedoniens Produkte sind gefragt. „Uns fehlt nur noch ein Toskana-Image“, meint Kazakis, „aber daran arbeiten wir gerade.“

Als ich wieder im Auto sitze, fällt es mir schwer, mich für ein Ziel zu entscheiden. Jeder, den ich auf meiner Reise gefragt ha-be, hat mir einen anderen schönsten Ort auf der Halbinsel ge-nannt. Also fahre ich sie der Reihe nach ab, die urigen Dörfer und verträumten Buchten auf Kassandra und Sithonia, dem westli-chen und mittleren Finger. Vorbei an duftenden Pinienwäldern, schroffen Steilküsten, bunten Bienenkästen und schneeweißen Schreinen. Ziegenherden zwingen mich immer wieder ins Schritt-tempo. Gut so: Wer hier zu flott fährt, verpasst leicht den Feldweg zum nächsten Traumstrand. An einem von ihnen, dem Portokali Beach, wo der Sand besonders weiß ist und das Wasser türkisfar-ben, stolpere ich in eine Hochzeit. Ein niederländisches Paar gibt sich vor zwei Dutzend Gästen das Jawort, barfuß unterm blauen Himmel. Der Anblick tröstet mich darüber hinweg, dass ich den östlichen Finger, Athos, auf meiner Reise nicht sehen werde. Wer die Mönche, die dort leben, besuchen will, braucht ein Visum, die Beantragung dauert Wochen. Frauen dürfen die Mönchsrepublik gar nicht betreten. Wer bei den Glaubensbrüdern weilen durfte, schwärmt von innerer Einkehr und unberührter Natur.

Am Abend sitze ich am Elia Beach in Nikiti auf der Terrasse eines alten Steinhauses mit sensationellem Meeresblick. Die ehemalige Schutzhütte für Landarbeiter ist seit Generationen im Besitz der Familie Koufadakis. Vor zwölf Jahren haben sie hier das Mpoukadoura eröffnet, eines der besten Restaurants der Ge-gend. Wirtin Giota Koufadakis serviert Salat mit Meerfenchel und deutet auf eine Pinie, die auf der Spitze eines Felsens wurzelt. „Dieser Baum ist 64 Jahre alt“, sagt sie. „Wind, Wetter und das viele Meerwasser im Boden machen ihm das Leben schwer – aber er hat sich durchgebissen.“

Mein Teller ist leer, die Sonne längst versunken, erst da wird mir Giota Koufadakis’ Gleichnis klar. Sie meinte mehr als die Pinie. Sie meinte die Hoffnung auf Wandel. Für ganz Griechenland.

Griechenland Greece

ThessalonikiChalkidiki

Ägäisches Meer Aegean Sea

Athen Athens

40 Lufthansa Magazin 8/2015

travelGriechenland

[e]

[d]

32_LHM_Hellas_neue_Helden.indd 40 26.06.15 11:16